When Ramona Torres sees stories in the news like that of three Cleveland women who were found after a decade of captivity, she is happy for the families.

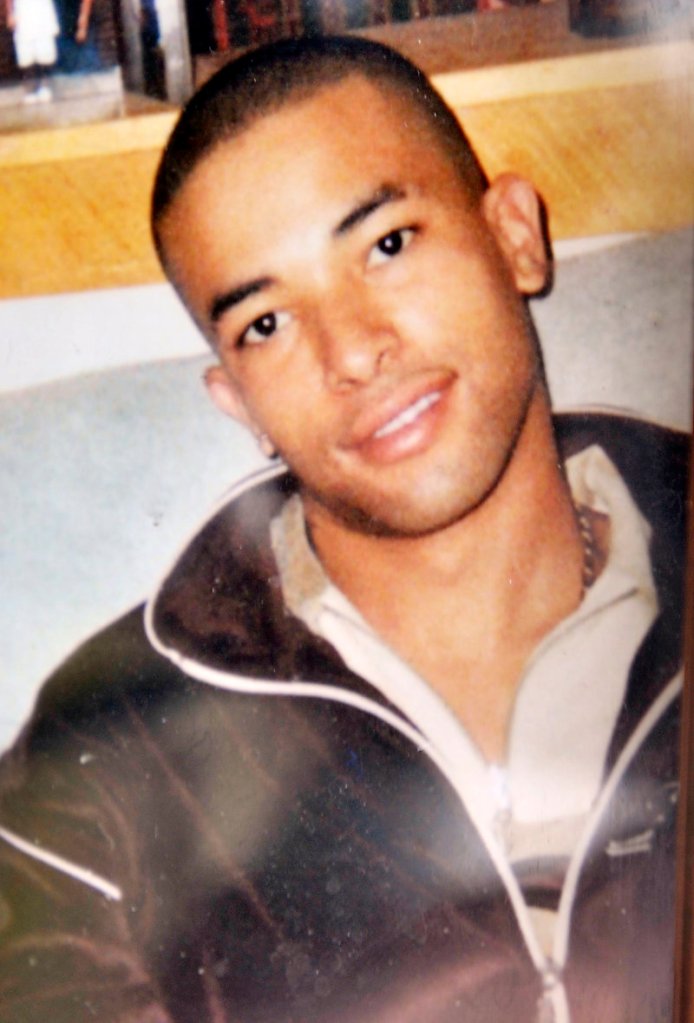

But it doesn’t make her hopeful. It magnifies her pain, if that’s possible. Her son, Angel “Tony” Torres, has been missing for 14 years.

“When is it our turn?” she said, sobbing. “When is my turn?” The last time she saw him was Mother’s Day, 1999.

Police believe the 21-year-old was a victim of foul play, but have no body and no crime scene.

Ramona and her husband, Narciso Torres, of Denmark, also believe their son Tony is dead.

As the anniversary of his disappearance approaches next week, they are hoping that somebody will provide information that will give them some peace.

“We would like to know for sure he’s no longer with us,” Narciso said. “When someone dies, you have a get-together to honor the person, to say your proper goodbyes, and we haven’t really had that opportunity.”

“What we want to do is find his body and bring it home,” his wife said.

Angel Torres was 6 years old in 1984 when his parents moved to Maine with him and his brother Luis, nine years older. A few years later, his brother Jamel was born.

He attended Bonny Eagle High School, then transferred, graduating from Fryeburg Academy. He won awards playing soccer, basketball and baseball, and got decent grades even without working hard, his mother said.

“He was very bright,” Ramona said. He was popular and loved to entertain. He liked girls, loved dancing and liked the New York Yankees.

“I grew up in the Bronx, my husband in Brooklyn,” she said. “Growing up in the Bronx wasn’t easy for me. I was lucky to get out of there alive. We always talked about how fortunate we were to be here. How fortunate they were to be here.”

Angel was known as Tony because in Maine, Angel is a girl’s name.

He resisted speaking Spanish at home with his parents, but studied it for four years in high school and was getting a minor in Spanish at Framingham State University in Massachusetts, along with a major in psychology.

He was finishing his junior year when he called home to announce he was moving in with his girlfriend. His parents insisted he come home to discuss it.

Narciso, a special education teacher at Bonny Eagle High School and an umpire for after-school sporting events, had a heart-to-heart with his son, complimenting him on his maturity. He told his son that he just wanted to make sure Torres was growing in the right direction.

His parents decided he was ready for the change and wished him well. They next heard from him on Tuesday, May 19, when he called to wish them a happy anniversary. It was 5 p.m., suppertime, Ramona recalled. He said he would call in a couple of days when he got a phone.

Ramona couldn’t shake a feeling of dread that something would go wrong. When Tony called a couple of days later, nobody was home, so he left a message. She listened to it over and over. When her husband asked if she was going to erase it, she said no.

The next day, Ramona paged Tony on his pager, which he carried in the days before cellphones. He didn’t call back.

“Rapidly it started getting worse for me. I started getting really emotional inside,” she said.

She finally spoke to a friend who said Tony had headed to Maine, that his girlfriend had dropped him at the bus station a couple of days earlier.

The girlfriend told his parents that he had gone to Maine to buy stereo equipment for the new apartment. When he didn’t return right away, she thought maybe he had gotten cold feet about moving in with her. She didn’t think to call his parents.

They called police.

The Oxford County Sheriff’s Office determined the disappearance was unusual for a young man who normally called home regularly. He had missed the start of his summer job at the same restaurant where his girlfriend worked.

The case was passed on to the Maine State Police, who handle most of the state’s homicide cases. Lt. Walter Grzyb was a detective at the time.

“We were trying to identify everybody he knew,” Grzyb said. “What we determined was the last place he was seen was basically Biddeford.”

Police said one witness saw him dropped at a Biddeford store at 2 a.m., and another saw him getting into a pickup. That was May 21, 1999. Police suspected he was heading north to the North Conway area.

His family put up posters around the city. They also confronted the possibility their son was involved in buying or selling drugs.

“We have been pretty open that drugs were related to his disappearance,” Grzyb said.

It was actually Tony’s parents who wanted that known, he said.

“They didn’t want everyone to think it was some kind of secret so people wouldn’t come forward” for fear of divulging that detail, he said. “Their priority is finding Angel. More than anything in the world that’s what they want.”

Grzyb lives in the same area as the Torreses. They see other frequently and Grzyb stops by to visit, especially around this time of year.

“They’re just very nice, decent people,” Grzyb said. I think it’s important they know the case isn’t forgotten. … It frustrates them. It frustrates me.”

Police have made progress and are hoping new attention will turn up new leads, said Lt. Brian McDonough, head of the state police major crimes division in southern Maine. The case has been assigned to a new investigator who will develop a new investigative plan.

“We have a couple people we’re interested in that probably have a little more information than they were originally forthcoming with,” McDonough said. “We’re in the process of following up with them again.”

McDonough called it a challenging case. “Obviously, we suspect foul play,” he said. “We don’t have any crime scene. If he was a victim of foul play and he was murdered, we don’t have anybody.”

In the months after Tony disappeared, his family offered a $5,000 reward for information leading to his recovery.

Now they hope that time will have changed people, made them more willing to help.

“We know someone in that area knows what happened,” Ramona said. “Maybe they were 21-year-olds at the time, maybe by now they’re 35 years old. They can understand, put themselves in my place. If they have a child of their own right now, maybe then they can say something.”

For now the family has a memorial garden in the front yard, with a basketball and a picture of Tony. It is dappled with daffodils. In time, they will give way to tulips, irises, pansies, roses and bleeding hearts.

“I go there and I talk to him when something happens to us,” Ramona said. When his younger brother Jamel graduated, first from high school, then college, and then when he got his master’s degree, she shared it with Tony in the garden, near a large tree and boulder he climbed on as a young child.

When they find him, they plan to cremate his remains and put the ashes in his garden.

Ramona says that while she stays emotionally strong, the daily anguish has taken a heavy toll.

“How can I have faith in God when people say, ‘Only God knows’? It’s been 14 years. How long he’s going to keep that from us?” she said, her voice raw with emotion.

“I’m very bitter with God. … How can you put a mother through this?”

This is the first time Ramona has made the appeal for help. In the past, her husband was the spokesman because she didn’t feel up to it.

Now she does. She said she gains strength from talking to the media.

Narciso said the pain of not knowing never goes away.

“It’s always there in the back of your head. There are moments when something or people will remind you of him and you tend to get a little emotional,” he said. “It just does not go away. It’s there. It’s awful. It’s a nightmare.

“You have to keep in mind you have other children, a wife that needs you. You have to keep it together. You have your little moments where you kind of cry by yourself. You just miss him.”

Ramona and Narciso have not celebrated their anniversary since their son called for the last time to wish them a happy anniversary.

This year, Ramona and Narciso Torres will try celebrating for the first time in 14 years.

Narciso said he’s willing to try. Ramona said she wants to think positive.

“We’re trying to move forward but it’s hard,” she said.

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.