I associate the George Marshall Store Gallery in York with some of the most coherently handsome gallery shows I have seen in Maine: Good art that looks good together.

The venue itself is just as quirky (and cool) as you could expect of a 19th-century store overlooking Maine tidal waters. But “Silent Spring” is a different kind of show than what you usually see in commercial galleries that privilege the eye over thematic.

It’s not some excuse to show the verdant abundance of blossomy landscapes. It’s a serious show about a serious topic — more of a curator thing than what you would expect from a gallery director whose job it is to sell art.

So I tip my hat to gallery director Mary Harding for curating a serious show that succeeds and, more importantly, helps represent the community of Maine artists as intellectually and environmentally engaged.

After all, Maine’s environment is our greatest resource. Our sportsmen leaders like Gov. Baxter — with rod and rifle in hand — have long been environmental leaders as well as economic pioneers.

It’s easy to argue that no one has done more for the awareness of Maine’s environment than our greatest artists such as Church, Homer, Welliver and our best contemporary painters such as Tom Hall.

Many people reading this will have instantly made the connection to Rachel Carson and her seminal book “Silent Spring” that was published in 1962. For my wife, Carson was an “environmental pioneer” and a “hero.” But I grew up in Waterville, so for me, environmentalism was Ed Muskie’s Clean Water Act and the angry gobs of chemical foam in the dead Kennebec that finally faded to memory and let the fish return.

Turning on a thematic instead of an aesthetic, Harding’s “Silent Spring” didn’t greet me with the winsome welcome I expect from her shows. Yet it has just the right touch to present the concerns of the show as running deep in Maine art.

I was so absorbed in the artistry that it took me some time to internalize the show has an environmentalist core; after all, any piece in the show is strong enough to stand on its own.

In other words, “Silent Spring” is serious without being shrill.

Judith Allen-Efstathiou is one of Maine’s most compelling artists (despite her having one foot away in some classical country), and her grid of 12 framed drawings is the main gallery’s largest presence. They map the monthly flora and their seasonal cycles.

It’s beautiful work driven by a conceptual project, astute observation and something like spiritual dedication to the landscape — a little more John Muir, maybe, than James Audubon, although a mixture of both.

The comparison that most intrigues me in this show is John Knight’s “Forget-Me-Not Drawing 2” hanging across from Julia Zanes’ “Two Headed Blue Bird.” While Knight’s self-questioningly spare drawing works hard to get its reductive passages right, Zanes’ decoratively primitivist and lusciously indulgent work builds up its rhythmic layers like fruit and flower garnishes on a fabulously frosted confection.

I like them both, but this setting helped me truly appreciate Knight’s decision-oriented works as process pieces rather than as more economically reductive pictures in the vein of Lois Dodd. Still, his “Daisy Fleabane Drawing” succeeds whichever way you prefer to see it — it’s a model of artistic restraint.

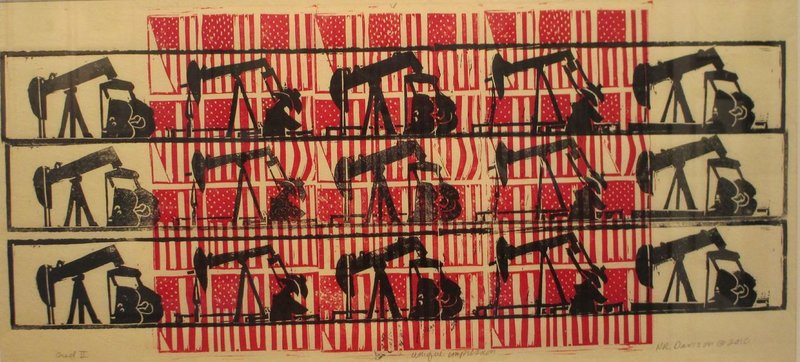

My favorite works in the show are Jane El Simpson’s phytoplankton-inspired paper construction pictures, Dudley Zopp’s trio of “Geologics” canvases and Nancy Davison’s proliferation-oriented linocuts.

Davison’s “Grid II” powerfully mismatches a 3-by-5 grid of black oil rigs over a more squat, sub-gridded 3-by-4 red layer of factory plants that juts out on the top and bottom. It quietly implies the math of caustic expansion as opposed to concerted organic growth.

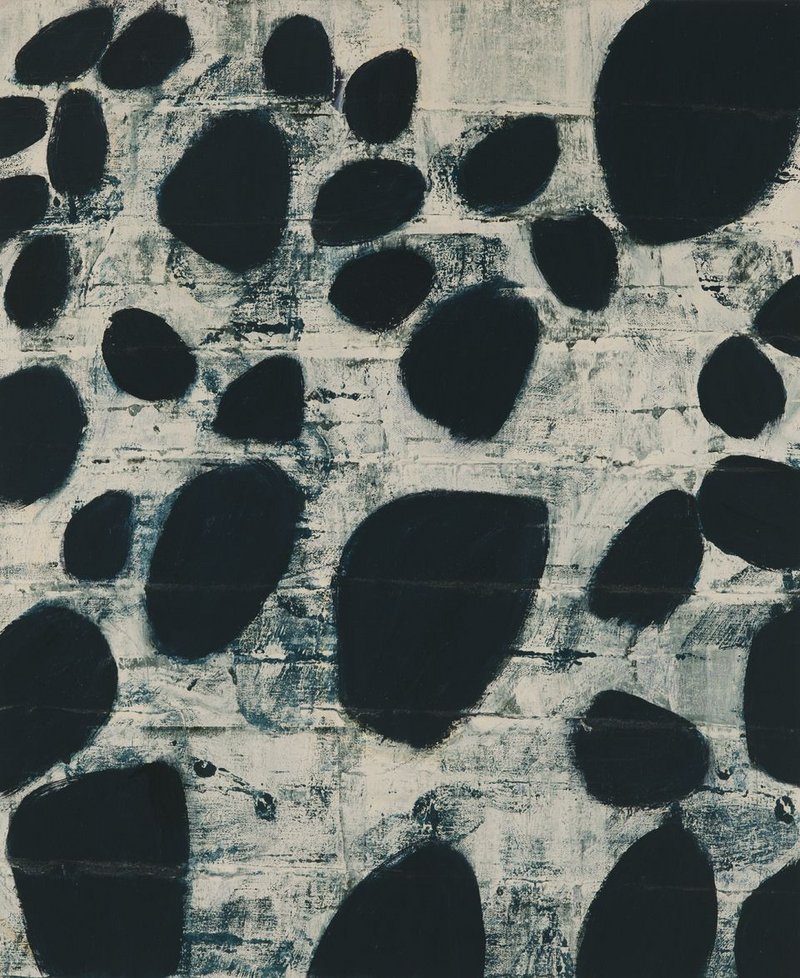

Zopp usually allows her materials to assert their inherent mineral logic, but here she gives us jaunty, pulsing black rocks on a white ground that seems to breed human presence like a virus. Her surface intercessions become more and more violent until they seem razor-slashed in the center painting. Zopp’s aggressive edge appeals to me.

Simpson’s assemblage pictures are microscopic images writ large in paper, thread and bits of organic flora such as thorns or pine needles. They are elegantly minimal and beautifully presented.

The weirdest thing in the show — by far — is Tim Gaudreau’s video documentation of a performance of what looks like a coven of bee-worshipping dancers. While the issue of bee deaths is genuinely important, this video made me want to text Hansel and Gretel to tell them to stay out of the orchard.

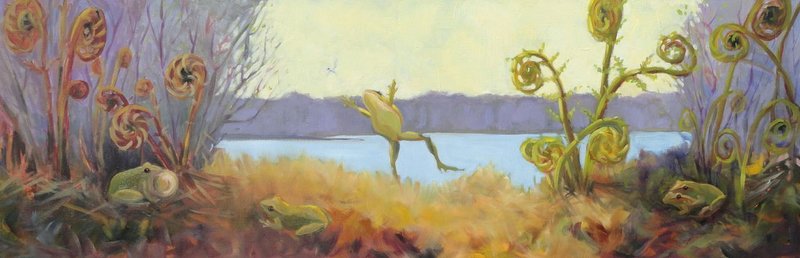

The most entertaining piece is Vanessa Nesvig’s “Joy of Spring Desiring,” a horizontal and fiddlehead-filled frieze of frogs performing nature’s birds-and-bees ritual. Nesvig can paint (her tiny bee paintings are gems), and she clearly has a flair for jocular theatrics. Above an audience of his otherwise-engaged peers, an athletic bull frog revealingly leaps (think Baryshnikov) for his moth-y dinner. It’s not just tongue-in-cheek, it’s hilarious.

While the humor of Nesvig’s froggie-went-a-courtin’ painting is a welcome exception, appropriately, it is the exception to the serious theme of the show. Yet through what could be a tough subject, “Silent Spring” is appealingly elegant, respectful and dedicated. So, while it’s smart, it is an easy show to enjoy.

“Silent Spring” may not be as handsome as other shows organized by Harding, but in some ways, it’s even better.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.