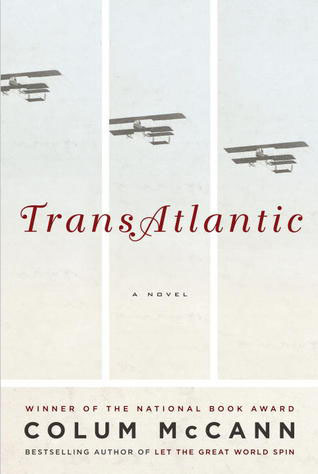

The opening three sections of Colum McCann’s new novel are gripping, immersing and suspenseful, written in words that sing. Each could be a great short story on its own, with fully developed characters caught in history-making moments. But could they be linked into a cohesive whole, a novel?

The answer, thankfully, is yes. The first half of “TransAtlantic” is so strong, readers would be terribly disappointed if the rest didn’t hold up. McCann, a National Book award winner for “Let the Great World Spin,” does more than that, elegantly linking his sometimes disparate characters through themes of identity and history, tying them together in subtle ways that build through the span of 150 years. The echoes of Ireland and its diaspora — McCann was born in Dublin but lives and teaches in New York — also run through the narrative, another unifying factor.

But mostly, McCann pulls it off through his seductive writing. His words carry the story on a current that feels like a force of nature. In vivid, short bursts of sentences, he follows the internal stream-of-consciousness of his characters, wrapping the reader in words. His writing is gutsy and controlled, powerful in its focus.

The book begins with figures straight from history: aviators Jack Alcock and Arthur Brown, attempting the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic to Ireland in a modified World War I bomber; escaped slave Frederick Douglass on an international lecture tour through famine-plagued Ireland to build support for the abolitionist cause, and U.S. Sen. George Mitchell, son of an Irish-American father, trying to build a lasting peace in Northern Ireland amid suspicion and deep bitterness.

Within those three different stories of crossing the Atlantic, McCann sows the seeds of the stories that follow. An Irish housemaid named Lily Duggan, who meets Douglass, reappears later in the book, followed by her daughter and granddaughter. The lives of the women — the second half of the book — are explored in greater detail than the men’s, showcasing the hardships the women faced and the hopes of previous generations that resided in them. Perhaps the emphasis on women is McCann’s way of saying that although men traditionally take center stage in history, women’s lives can have just as much import, especially in determining the daily warp and woof of life.

Adding a layer of intrigue to the women’s lives: A letter from a mother and daughter to a family in Cork is sent on the plane with the two aviators. If it arrives on Ireland’s shores, it will be among the first trans-Atlantic letters ever. “What a surprise is it when distance finally breaks,” one of the letter-writers thinks.

But the letter will remain unopened on the other side of the Atlantic for generations, a paper question mark, a crumbling envelope filled with promise. Could it have links to Douglass, making it valuable for history’s sake? And once opened, would it lose all value? McCann toys with the idea of the letter, of writing, of storytelling itself, as something that ties generations together. All stories, he notes, have to look backward as well as forward: “We seldom know what echo our actions will find, but our stories will most certainly outlast us.”

He bookends his novel with scenes from a single house by the water. In the prologue, a woman listens to sounds coming from the roof — a ping, then a rumble — as gulls drop oysters on the slate roof to break open the shells. At the conclusion of the book, the house returns with greater significance, a symbol of family and history and the sometimes mundane intersections that make up a life.

For McCann, though, there is also always the view from afar, the one glimpsed on those trans-Atlantic crossings, where the bigger picture reveals itself like the miracle of earth slipping away beneath the wings of a descending plane:

“In the distance, the mountains. The quiltwork of stone walls. Corkscrew roads. Stunted trees. An abandoned castle. A pig farm. A church. And there, the radio towers to the south. Two-hundred-foot masts in a rectangle of lockstep, some warehouses, a stone house sitting on the edge of the Atlantic. It is Clifden, then, Clifden. The Marconi Towers. A great net of radio masts. They glance at each other. No words. Bring her down. Bring her down.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.