WATERVILLE – Sharon Corwin didn’t allow the pressure of installing one of America’s most valued private art collections to get in the way of her having fun.

“A blast,” she said. “It’s been a total blast. It’s been a real honor to work with this collection.”

Corwin, director and chief curator of the Colby College Museum of Art, shows off the result of her work when the museum fully reopens to the public on July 14 with “The Lunder Collection: A Gift of Art to Colby College.”

The centerpiece of the reopening is the 26,000-square-foot Alfond-Lunder Family Pavilion, a jewel of a building that gives Corwin and her staff the opportunity to show the range, depth and aesthetic magnificence of the Lunder Collection.

The promise of the gift of more than 500 pieces, assembled by a Maine couple, came in 2007. Since then, Corwin has been thinking about showing it off. During that time, she had rare access to the artwork, giving her the chance to live with it, ponder it and wrap her mind around its many nuances, characteristics and traits.

Beyond working with an architect to shape the new wing and a construction team to build it, Corwin’s challenge was making sense of an art collection formed over four decades by two individuals, Peter and Paula Lunder.

The Waterville couple built their collection based on the advice of art-world friends and confidantes, but the collection ultimately reflects personal tastes and their evolution as collectors. Their collection represents the broad spectrum of American art, dating from the early days of the country to the present.

As their vision is refined, the couple continues to collect. They began driving around to antique shops across Maine, buying pieces that caught their eye. By the late 1970s, the Lunders became more serious, and concentrated on European paintings.

When prices for European art soared, the Lunders shifted gears and collected American art, focusing first on art from the American West, a personal interest of Peter Lunder, then concentrating on American masters, many with ties to Maine: Edward Hopper, Winslow Homer, Andrew Wyeth.

As their tastes and sense of art-buying adventure expanded, they gravitated toward sculpture and contemporary art. They took more risks and went further afield aesthetically.

For the opening, Colby shows slightly more than half the collection.

When visitors enter the museum’s new lobby and pass through the big glass doors into the Alfond-Lunder Pavilion, they will immediately sense a modern museum experience. Large, glittering contemporary pieces in silver, neon and flashing lights anchor the interior walls.

The galleries are tall, spacious and bright, and filled with a curious mix of late 20th- and early 21st-century art that provokes humor, awe and wonder: John Chamberlain’s wall-hanging sculpture “Rare Meat,” a twisted mix of steel that looks something like a car crash; Maya Lin’s “Pin River — Kissimmee,” which offers an outline of the Florida river with hundreds of steel pins affixed to the wall; and Donald Judd’s untitled sculpture of copper and orange Plexiglass, which looks something like a modernist wall shelf.

Later, visitors weave back into the 19th and early 20th centuries with work by American masters John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt, George Inness and James McNeill Whistler. Indeed, the Lunder Collection includes many remarkable works by Whistler, including his 1864 painting “Chelsea in Ice” and more than 200 etchings and lithographs.

For this inaugural exhibition, which will be on view for a year, Corwin grouped much of the work into themes: The working waterfront, world views, the natural world, masculine pursuits. In the future, she will integrate the Lunder Collection with the rest of Colby’s holdings, using the Lunder pieces to complement the existing depth of the museum’s collection.

With almost 300 pieces of art on view, the Lunder Collection demands time and attention for digestion.

“The range is what is so impressive,” said Corwin. “I think people will be surprised and astounded with what they see. As you move from one gallery to the next, each one is a revelation. What we had to do was figure out how to make it make sense in relationship to itself.”

With that in mind, here is a guide to enjoying this inaugural show with a focus on 10 key moments.

1. The first moment of wonder comes quickly, courtesy of Swedish-born sculptor Claes Oldenburg. His oversized “Typewriter Eraser” sits in the middle of the first gallery, beckoning people to come for a closer look and begging the question that’s on the lips of anyone born in the post-typewriter era: What is it? It’s a perfectly realistic, three-dimensional representation of the old wheel eraser with bristles.

Across the gallery, Oldenburg’s “Model for Clothespin” — a bronz-and-steel rendering of the common wooden clothespin — helps us appreciate the form and function of a common utilitarian domestic object.

2. Two paintings by Maine-based Richard Estes command attention: “Mt. Katahdin, Maine” from 2001 and “Columbus Circle at Night,” from 2010. Estes is known for his photorealistic paintings. These two show the contrast in his work and his worlds, from a remote region of rural Maine to the heart of Manhattan.

3. Perhaps the most startling piece in the contemporary galleries is Duane Hanson’s “Old Man Playing Solitaire.” Hanson created a perfect human form, dressed him in old-man clothes, and placed him at a battered card table with a deck of cards mid-deal in a game of solitaire. A sour coffee cup sits off to the side.

It’s so realistic, with the old man’s hair drooping across his forehead and his eyes cast down at his cards in contemplation, one almost wants to hang around and see not whether he wins his game, but by how much.

The old man freaks people out, Corwin says. “He does. He totally does.”

But his presence in the Lunder collection also highlights the collectors’ commitment to sculpture, Corwin added. The Lunders broke far from traditional bronze and marble, and encouraged contemporary sculpture in non-traditional media with their purchases.

4. Along those lines, among Corwin’s favorite pieces in the collection is another utilitarian effort: Jenny Holzer’s granite bench “Under a Rock: Crack the Pelvis.” Holzer has chiseled a poem memorializing a violent death into the seat.

It’s a perfectly functional piece of furniture that doubles as a piece of art, and it demonstrates the Lunders’ growth as collectors and their willingness to expand their own personal horizons. Corwin has placed it in the heart of one of the spacious open galleries, inviting visitors to sit on it.

5. John George Brown’s painting “Watching the Circus” is one of those pictures that visitors will return to over and over. It depicts a group of 13 children and one dog standing alongside or sitting on a rail fence in a country setting. Some of the kids are wearing shoes; others are barefoot. All but one wear hats to shield the sun, which bears down and casts dark shadows.

It’s a period piece from the late 1800s, and an engaging study in the joy of youth. The title implies that these kids are watching a circus, and the effect of their poses is a wall of wide-eyed innocence gazing out from the canvas.

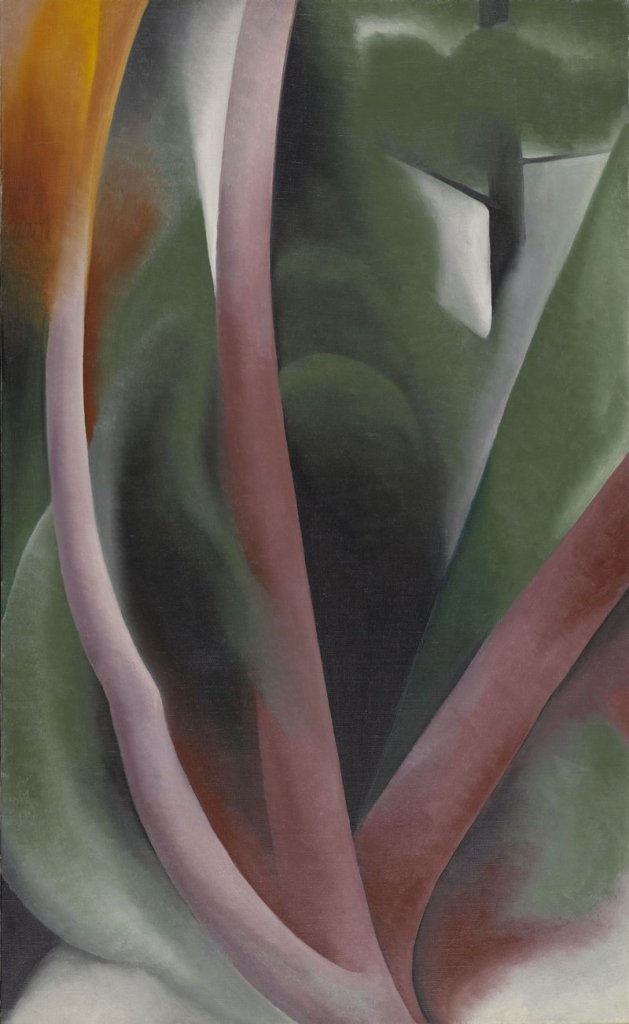

6. Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Birch and Pine Trees — Pink” from 1925 is a study in form and color, and provides an exceptional example of the artist’s ability to blend and merge colors while creating an abstract image of her rural home.

7. In Maine, we’ve had great opportunities to experience the artwork of Winslow Homer. The Lunder Collection offers several Homers, including the restful “Girl in a Hammock” and “The Noon Recess” from 1873. In the latter, young boy is forced to stay in the classroom during recess while his friends frolic outside, clearly visible to the boy and his unhappy, sour-faced teacher.

8. The Lunders’ holding of Whistler paintings and works on paper is extensive. Perhaps the most important Whistler oil in this collection is “Chelsea in Ice” from 1864. A stark, cold canvas painted in an impressionistic style from Whistler’s London home, it shows a near-frozen Thames River, with ships struggling to pass.

Also not to be missed: Whistler’s etching “Finette” from 1859, an exquisite rendering of a cancan dancer dressed in black and leaning against a wall.

9. Terry Winters’ “In Blue” from 2008 is considered a monumental painting. Winters created a grid of knotted forms, playing with shape, size and color. The knots emerge from the painting in a loose grid, and take on many visual forms.

Another painting in this series is called “Tangle,” and the two pieces together suggest an homage to Bob Dylan’s song “Tangled Up in Blue.” In a catalog essay, Winters acknowledged the connection between Dylan’s song and his own paintings.

10. Finally, the Alfond-Lunder Pavilion is a work of art itself. Corwin encourages visitors to pay attention to the details of the building: Its corners, its hallways and recesses.

Art is everywhere, including behind an exterior-facing glass wall. A three-story Sol LeWitt wall painting in bands of yellow, blue and red extends the height of the walls, and is visible to the world passing outside the walls of the museum. The LeWitt serves as an invitation to come in and explore, Corwin said.

“We want this to be a building where people can experience art in many different places and in many different ways,” she said. “The skin of the building is a canvas, and the building is about seeing. Wherever possible, we have incorporated artwork into its surfaces and it its seams.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.