State education officials and Gov. Paul LePage wanted a new A-F rating system of Maine public schools to spur change and improvement, but local school leaders say its influence so far has been small or nonexistent because it lacks funding, rewards, penalties and significant assistance.

School leaders say the controversial report cards didn’t tell them anything they didn’t already know and that they’ve received little help from the state since the grades were released May 1. Legislation that was supposed to expand school improvement efforts failed in the spring.

As Maine schools prepare to reopen to students this week and next, many will continue with plans they’d already made to try to improve student achievement.

At several schools, the grades aren’t a factor at all in those plans.

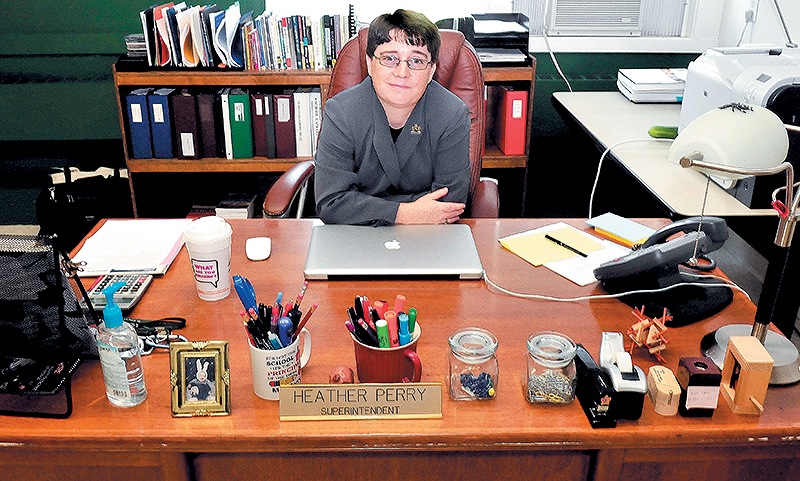

“We feel very strongly that we already knew our weaknesses; the grades were not news to us,” said Heather Perry, superintendent of Unity-based Regional School Unit 3, which had several schools with low grades. “We already had plans in place to improve those achievement results, and we’re not deviating from those plans. The grades really didn’t do anything other than distract parents and others politically that this was some huge change in the system, when it wasn’t.”

The state’s A-F report cards for schools are supposed to get the public more involved in education and direct support for school improvement to the places where it’s needed most. But there are no practical consequences of the grading system, and some school officials, parents and real estate agents say it also hasn’t started the sorts of conversations about education that were intended.

Marcia Buker Elementary in Richmond received a C, and parent-teacher group president Samantha Johnston said people there talked about the grading system not accurately reflecting the school and state cuts to education funding.

“As far as getting a conversation started, it definitely did that, it definitely got people talking, but nothing with any sort of positive connotation,” Johnston said. “Here’s the problem, but what’s the solution?”

The Department of Education has called and met with officials at schools that received a D or an F, and department officials believe the grades have created a new urgency around school improvement among school boards, administrators and educators.

“I’m encouraged by the calls we’ve gotten and the change in attention to the data,” Chief Academic Officer Rachelle Tome said. “I think we’re going to see some exciting things happen this year, I really do.”

This year, Biddeford Middle School is adding a block of time for customized instruction and enrichment — something Principal Charles Lomonte said the school probably would have done anyway, but the D grade and data gave it an extra push because they confirmed problems with the progress of underperforming students.

“It helped us ask the right questions,” he said. “I think time will tell whether the process works.”

Statewide, the most common grade was a C. Among elementary and middle schools, there were 42 A’s, 52 B’s, 215 C’s, 53 D’s and 49 F’s. There were 40 A-rated high schools, 22 B’s, 66 C’s, 15 D’s and 18 F’s.

NO MONEY FOR IMPROVEMENT

At least two studies of Florida’s A-F grading system, which was a model for Maine’s, have shown that staff at F schools responded by making changes that improved student performance. Stigma is a consequence for low-rated schools, the reports say, but what schools really responded to was a provision that gave school choice to students at schools with repeated F grades.

There’s nothing like that in Maine’s grading system. A low grade does not create any new requirements for a school, nor for the Department of Education in support of a low-rated school.

A week after unveiling the A-F system, LePage’s administration submitted a bill, L.D. 1510, to provide assistance to struggling schools and to revoke a school’s approval and give its students school choice if the school failed to adopt or follow an improvement plan.

The bill, which was rejected by the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee along party lines, did not specify how schools would be identified as needing improvement. Opponents worried that the A-F grades would be a factor.

The Legislature also removed $3 million that LePage included in his proposed two-year budget for an Office of School Accountability within the Department of Education.

“There was this line-item reference to the accountability office, and there was no explanation forthcoming as to what that actually meant, how the accountability office was going to work, how it was going to be staffed, what the money was going to be used for,” said Sen. Rebecca Millett, D-South Portland, the education committee’s Senate chairwoman. “Based on that, we did not feel comfortable approving $3 million.”

Department of Education spokeswoman Samantha Warren said it’s understandable that legislators wanted more information, and the department has spent the summer gathering feedback from schools about how to support school improvement.

“We didn’t make the case as well as we could,” Warren said. “And frankly, we couldn’t make the case because we didn’t have responses from schools about what they needed.”

Both L.D. 1510 and the accountability office were part of an attempt to expand school improvement efforts beyond the federal initiatives that have been in place since passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001.

Under that law, and the waiver Maine recently received from some of its provisions, standardized test results and progress are reported for all schools, but only Title I schools are eligible for federal assistance or subject to consequences if they fail to meet targets.

About 65 percent of Maine schools, mostly at the elementary and middle school levels, are part of Title I, which provides additional federal support to schools with significant numbers of low-income students.

All Maine schools would have been eligible for help from the Office of School Accountability.

Warren said they would have used the money to hire staff to help schools develop improvement plans, offer instructional training and coaching, provide grants to schools and districts and bring in another person to help schools analyze data to identify problems and solutions.

“Without that funding, we still intend to be a statewide support system to schools to complement the statewide accountability system, but we’ll just need to do so with existing resources,” Warren wrote in an email.

With less funding available, the department is focusing on schools that received a D or an F, also referred to as underperforming schools.

Near the end of last school year, the department started sending staff members to interview administrators at underperforming schools about their existing improvement initiatives, professional development happening this summer, the schools’ needs and what the Department of Education could do to help.

‘LOOK AT YOUR DARN DATA’

In interviews, some school administrators were critical of the grading system because it lacks assistance.

Some asked for things that could be expensive, like regional training sessions, department analysis of data to be provided to school staff, and more funding for public schools in general.

The most common requests, though, were for information. That would be relatively inexpensive and fits the department’s function, as described by Warren, as a connector and facilitator. Administrators asked for the department to identify best practices supported by research and to help them find and communicate with demographically similar schools that are having success.

“They’re asking us to let them know what schools are working on, what projects, and which are being successful so that they can collaborate,” said George Tucker, a school improvement specialist at the state Education Department. “Maybe we haven’t asked that before, but we haven’t really heard that before.”

The Department of Education ran a series of four webinars in June, with topics including the characteristics of effective schools and the practices of low-income but high-performing schools. There were supposed to be more webinars at the end of the summer, but none have been announced.

The Department of Education is not able to access data about how many people have watched the school improvement webinars or used the Maine Education Data Warehouse, Warren said, although the data warehouse website did crash from being overloaded in the first two days after the report cards were released.

Tome said feedback from the administrator interviews will be used to choose topics for future webinars. Department staff are trying to dig into data and collaborate more across teams, just as they’re advising local school leaders to do.

Money helps, department officials said, but so can focused planning or careful analysis of data to identify the root causes of low achievement.

“Lots of schools know what they need to do next, but there are barriers,” Tucker said. “Some of them are simply financial, to getting those things done in a timely way. And others are a little more struggling to try to do 100 things at once, and they’re just a little overwhelmed by all the things that they’d like to do rather than having a comprehensive, long-term plan for improvement.”

There was immediate resistance to the A-F system — some educators said it unfairly stigmatizes schools in poorer communities — but Warren said even the mostly critical letters that administrators sent to parents shortly after the report cards were released showed new focus and urgency about improvement.

“The last paragraph would say, ‘But they’re right, and we know we’ve needed to change this, and we’re going to change this,”‘ Warren said. “They’re calling us to say, ‘How can we change this?”‘

Tome “has been screaming, jumping up and down on her soapbox for a decade, saying look at your darn data, and now they’re looking,” she said.

Warren said the department receives calls every day from school leaders seeking help with data.

WHITEFIELD GETS NO HELP

Not all school districts have engaged with the Department of Education’s follow-up to the report cards.

Administrators in RSU 54, where Skowhegan Area High School received a D, declined an interview with department staff.

Principal Rick Wilson said the meeting would have taken four or five hours, and district officials already know why the school got the grade it did. Standardized test scores and the graduation rate would have earned the school a C through the report card’s formula, but they were docked a letter grade for having 94 percent test participation, short of the 95 percent requirement.

Given all that school staff already do to get students to take the Maine High School Assessment, and the department’s inability to do anything about it, Wilson said the meeting would not have been a good use of time.

Wilson said he’s not sure what the Department of Education could do to help his staff with instruction, given that they face a financial squeeze just like local school districts.

“Their staff is so small and the needs so great, and they’re stretched so thin, I think they don’t have the capabilities to get in and do the work that needs to get done,” he said.

Tome said that beyond the participation issue, there are many other projects happening in schools this year to improve education. Now, they’re looking for feedback about what people need, she said.

Tome said department staff are compiling information from the first round of interviews and will try again to meet with leaders at the underperforming schools that did not participate, whether by choice or because of missed connections.

Wilson noted that Skowhegan Area High School was studied last year by University of Southern Maine researchers as an improving school, with potential lessons for other schools.

He’s confident that future report cards will soon show the impact of new initiatives, like a new policy last year that students won’t be allowed to graduate unless they can write and do math at least at the level required by Maine’s community colleges. The district is offering targeted support to students at risk of not meeting those standards, starting in seventh grade.

Principal Josh McNaughton of Whitefield Elementary, which received an F, also has not talked with Department of Education staff since the report cards were released. He said someone from the department called, and he tried calling back twice, but nothing was ever arranged.

Based on Department of Education officials’ statements when releasing the report cards, McNaughton thought the state might offer more professional development for teachers or provide staff to work with underperforming students.

He wasn’t counting on additional support from the state, but is disappointed that it hasn’t come through.

“I’m really disappointed that the state publicly said they would provide assistance to our schools, and it hasn’t happened yet,” he said.

Lomonte said the federal money, professional development and guidance that were part of the No Child Left Behind improvement process were hugely helpful to Biddeford Middle School, and replicating some of that on the state level would be more helpful than handing out letter grades.

Gardiner Area High School in RSU 11 was in a similar situation to Skowhegan, having received a D because participation on the 2012 Maine High School Assessment was 94.5 percent. Principal Chad Kempton said he expressed his frustration about the participation penalty to a Department of Education representative.

“I said, ‘Give me one more student and we’re a mid-C school, and we wouldn’t be having the conversation,”‘ Kempton said. “We’re really not an underperforming school.”

Kempton said one thing that would help his school improve is a full review by the Portland-based Great Schools Partnership. School staff will start working with the partnership’s best practices tool kit, which is available online for free, but there’s no money in the budget to work with the partnership on site, which can cost $25,000 or more.

FOCUS ON THE POSITIVE?

Kempton said he would welcome financial support from the state to pay for that, but he doesn’t know what the department’s capacity is to help underperforming schools.

Some school leaders said the department could help by publicly acknowledging and encouraging the hard work that educators are already doing.

Outgoing Education Commissioner Stephen Bowen has tried to focus on positives during his “promising practices tour,” during which he’s visited several schools, including some low-rated ones, that are having success with programs that could be repeated elsewhere.

Kim Silsby, principal of Cony High and Junior High schools in Augusta, said she’d like the department to focus more on highlighting success, sharing best practices and providing professional development opportunities.

“It definitely seems like there’s a tenor of, that public education isn’t doing what it needs to do at this time,” Silsby said. “We have so many successes that are not focused on. I think that we need our Department of Education to celebrate the successes of every school in our state. And so I think by giving schools grades based on a limited view of what’s going on in those schools, it’s not helpful.”

Juliana Richard, principal in Bingham-based RSU 83, which includes F-rated Upper Kennebec Valley High School, said she appreciated that the person who came to interview administrators was familiar with the school’s challenges from his previous work with the district through the No Child Left Behind accountability system.

“The good thing, I think, that came away was the fact that we got a chance to speak with the federal coaches that were already in place,” Richard said. “It was a trusting relationship, not just someone coming in after reading the newspaper.”

Susan McMillan can be contacted at 621-5645 or at:

smcmillan@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.