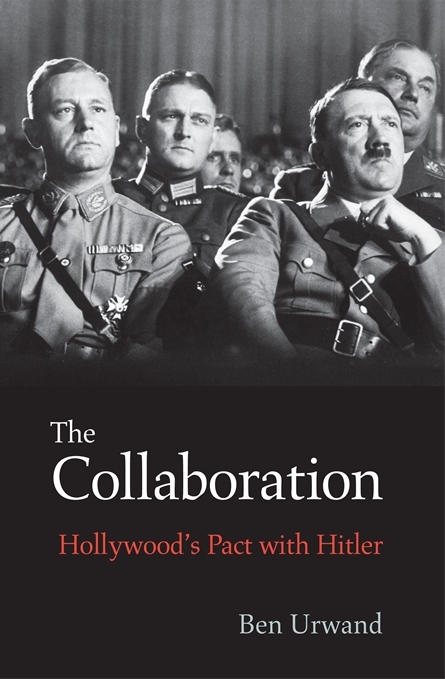

Using the loaded word “collaboration” to link Adolf Hitler and Hollywood may be interpreted by readers as a charge that the movie industry aided America’s enemy. Author Ben Urwand points to the term in correspondence from the period, but he fails to back up the premise inherent in the title of his book exploring the ways some U.S. studios bent to the will of Nazi Germany.

While “The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact With Hitler” contributes to our knowledge about U.S. films in the Nazi era, a surprising dearth of context undermines the author’s central thesis and leaves major questions unexplored. For instance, was there Hollywood “collaboration” with other fascist governments?

Yet, underneath the hyperbole of the title is a fascinating struggle. To keep distributing their movies in Germany in the 1930s, studios agreed to placate Nazi officials who sought to shape American movies for all audiences, not just those in Germany.

At the same time, the Nazis recognized the entertainment and economic value of American films and wanted to keep them in theaters.

As Urwand explains, the goal at first was nationalism. Nazi-led demonstrations drove the anti-war film “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930) from German theaters. Universal Pictures eventually agreed to reissue worldwide prints of the winner of the best-picture Oscar. Scenes of frightened German soldiers and other actions deemed hurtful to German national pride were trimmed.

After Hitler became chancellor, in 1933, the Nazi representative in Los Angeles persuaded movie executives to change scripts, edit films and avoid or abandon some projects.

The proposed anti-Hitler movie “The Mad Dog of Europe” drew the Nazis’ ire and was never made. When Warner Bros. ignored objections to the war film “Captured!” (1933), its movies were banned in Germany from then on.

A new goal emerged: keeping Jews off movie screens when practical. Nazi censors removed MGM’s “The Prizefighter and the Lady” (1933) from German theaters because its star, boxer Max Baer, was a Jew portraying a heroic winner. Later, Jewish names would be cut from the credits of U.S. films and a blacklist of individuals — anti-fascist artists as well as Jews — would be threatened.

By 1936, only three of eight leading U.S. studios — MGM, 20th Century-Fox and Paramount — were still willing or able to work with the Nazis. They continued to give in to Nazi concerns about anti-fascist films. MGM sanitized the plot of “Three Comrades” (1938), moved the setting to the pre-Nazi era and made other changes as the pressure continued.

Hitler invaded Poland in 1939 and the European market for films began to dry up.

The studios began releasing anti-Nazi movies like Fox’s “Four Sons” and MGM’s “The Mortal Storm” (both 1940), prompting Germany to ban all their films. (Paramount would be banished over its newsreels.) Thus, “the collaboration” actually ended while the U.S. was still neutral, and a year before Germany declared war on America.

A larger point all but ignored in “The Collaboration”: Hollywood was used to tailoring its product to avoid political and social criticism.

Urwand doesn’t consider the uncomfortable parallels between the censorship sought by Nazi Germany and that practiced by the U.S. film industry’s own Production Code, the Roman Catholic Church’s Legion of Decency, and state and local film boards.

Nor does he ponder how racial and ethnic stereotypes in U.S. films may have reflected views similar to those Nazi officials held for Jews. Urwand notes that Jewish characters disappeared from American films in the mid-1930s partly in response to Nazi pressure. However, he doesn’t relate that to Hollywood’s attitude toward people seen as politically and socially unacceptable, such as gays and mixed-race couples. Like Jews on German screens, they didn’t exist under U.S. censorship standards.

A stronger sense of movie history might have helped Urwand enhance the discussion — and avoid making the erroneous claim that, after the liberation of Europe’s death camps, “decades would pass before any reference to the crime appeared in American feature films.”

This overlooks “The Stranger” (1946) with Orson Welles as a Nazi hiding in America, “The Search” (1948) with Montgomery Clift, “The Juggler” (1953) with Kirk Douglas and “The Young Lions” (1958) with Marlon Brando. All refer to the Jewish extermination.

The studios were eager to get their films into theaters, American and German, during the Depression. Doing business with the Nazis was deplorable but on par with how the studios responded to similar pressures and attitudes at home. Hindsight only heightens their disgraceful business strategy, which casts a deep shadow on Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.