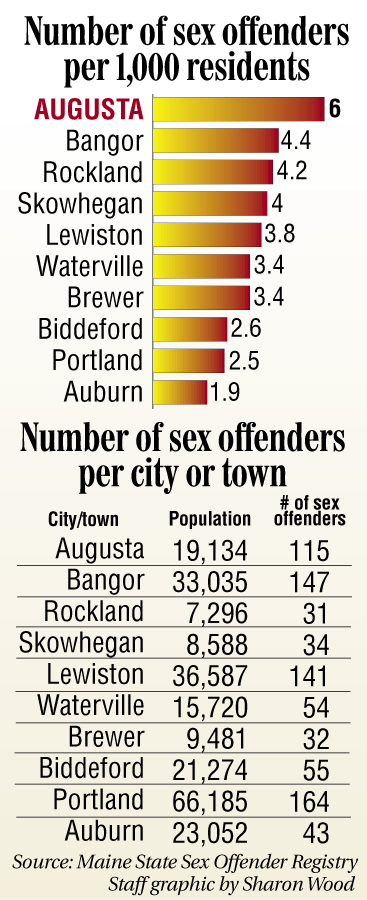

Much to the chagrin of parents, city officials and police, Augusta is home to more sex offenders, per capita, than any other Maine municipality.

Six out of every 1,000 residents of the capital city are registered sex offenders. That tops the next closest, Bangor, where there are 4.4 sex offenders for every 1,000 residents, Rockland, at 4.2, and the state’s largest city, Portland, at 2.5.

While the numbers don’t lie, they don’t explain why, either.

The reasons, according to city leaders, advocates, corrections authorities, landlords and parents, range from Augusta’s availability of relatively cheap housing, its urban setting where offenders without cars can get around easily, and easy access to a myriad of social services here, in part, because the city is the state capital.

But city officials and some residents, particularly those with children, complain the city gets more than its share of sex offenders fresh out of prison in part because corrections officials have established working relationships with local landlords willing to rent to sex offenders.

“There have been some concerns that the state Department of Corrections is placing sex offenders in Augusta, it almost seems like a matter of practice,” said Police Chief Robert Gregoire. “A lot of them didn’t live in Augusta (before they went to prison). The Department of Corrections, to some extent, may find it easier to have them in all together in a confined area, so they’re easier to visit and monitor. If I was in that line of work, that’s what I’d think about.”

It’s a claim corrections leaders don’t deny.

“It’s not uncommon at all for probation officers and caseworkers to develop a good working relationship with landlords,” said Scott Landry, superintendent of Maine Correctional Center, in Windham. “They get to know landlords who’ll work closely with them. There are some rooming houses and other places that have been willing to work with sex offenders, and will have a number living in one. Some landlords are very good about it. They interact with the department and work with us to make sure they’re managed safely. It is easier to monitor them when you have a number of them living in the same rooming house. Probation can be going through those kinds of places very routinely. It can be done safely.”

‘We don’t do this willy-nilly’

Of the 115 registered sex offenders in Augusta, 16 live in apartment buildings owned by Larry Fleury’s firm, River City Realty, according to cross-referencing research of the sex offender registry and the city’s property assessment database.

Fleury said by his count he is renting to 12 sex offenders. He said the reason he rents to more sex offenders than any other landlord in the city is fairly simple. He has more buildings than other landlords, with 23 rental properties totaling 170 units. And he has smaller, and thus cheaper, units available in the city, where his tenants can walk to work and services.

He said he’s careful in placing sex offenders in his buildings, screening and rejecting potentially violent offenders, and making sure sex offender tenants are not put in buildings with children.

“We dig into the history of people, we’ve turned down a lot of people because they’re violent,” Fleury said. “We don’t do this willy-nilly. To me, it’s giving them a foot in the door. A lot of these people are going to lead productive lives. It came on slowly for us, we took a few here and there and, I hate to say it, but they’ve turned out to be, for the most part, excellent tenants.”

Fleury said sex offenders who’ve served their time in prison come to Augusta because of the available housing and to be close to jobs, services and probation officers.

Probation officers sometimes call him looking for a place for a sex offender getting out of prison to live, he said.

Fleury said he does not recruit such tenants, they come to him.

“They contact us, it could be a probation officer, or it could be a tenant directly,” Fleury said. “For the most part it is tenants. We have no recruitment policy and don’t reach out to any agency. The only advertising we do is in the paper.”

Landry acknowledges a dilemma — the best places for sex offenders released from prison to live, unless their own family members are willing to take them in, are urban service centers, like Augusta, where they are more likely both to be more easily monitored by authorities and find the resources that allow them to make the best possible new start to their lives.

But those same places are, obviously, also going to have the most people, children included, living in them. And many people don’t want sex offenders as their neighbors.

Daycare, parent concerns

Resident Delora Dahlen Henderson lives, and has run a daycare center for two decades, next to a sex offender. But she said his presence concerns her less than what she estimates are the five other sex offenders living within walking distance of her Cony Street neighborhood.

“None of these children are ever out of my sight,” Henderson said. That includes not only her daycare charges, but her 4-year-old granddaughter. “Not because my neighbor is a pedophile, but because there are five others in the area. I have a responsibility not to let them out of my sight. People need to make themselves aware.”

Melanie Baillargeon, mother of two boys ages 7 and 12, said she is not surprised Augusta — where she lives in the same westside home where she was raised — has more sex offenders per capita than anywhere else in Maine.

“The landscape of my neighborhood, over the last 40 years, has changed significantly,” she said. “There are no little children on my street. There are very few resident-landlords in the buildings in my neighborhood, they’re are all out-of-staters.”

She said when she was 12 years old, she’d leave the house on her own for baby-sitting jobs. Now, she says her 12-year-old son doesn’t walk to the library by himself. Nor have her sons ever been to Cunningham Park, nearby on North Street.

“At the end of the day, I have to keep my children safe, and myself,” she said. “We talk about it throughout the year, what they should do if a stranger comes up to them and says ‘help me with my dog.’ You ask those questions and keep their minds aware. You don’t want them to be paralyzed by fear, but you don’t want them to be in a bubble, either. I feel fortunate the sense of community that Augusta has is still evident. In any community, there are extremes.”

Jim Pepin who rents to 10 sex offenders, according to the registry and city assessing database, the second most sex offenders of any landlord in the city, said he rents to them because it would be wrong to discriminate against them. He has 31 buildings, with 140 units.

Many of the city’s sex offenders live in the same parts of the city, often in the same buildings.

Five live in Pepin’s 388 Water St., just above the downtown area.

A section of Green Street which is just behind the 388 Water St. area, has sex offenders living in three different buildings.

And three sex offenders live in a Fleury-owned building at 34 Cedar St.

But it’s not exclusively an in-town issue. Out in the more suburban area of the city, at 458 Riverside Drive, four sex offenders rent units at the Country Village Motel and Apartments.

Discriminating against sex offenders by not renting to them is not illegal. Criminals are not a protected classification when it comes to housing discrimination.

“We treat everyone fairly and equally, we don’t discriminate against anyone,” Pepin said. “We check references, we have safeguards in place. If someone doesn’t behave, for any reason, or they’re going to be harmful to other tenants, we evict them. Overall, I’d say (sex offenders) are fine, just like the rest of the people we rent to. If you pay your rent, are kind and decent and behave, they can stay with us forever.”

Mayor William Stokes, who is also deputy attorney general and head of the criminal division of the Maine attorney general’s office, said the 115 sex offenders in a city of nearly 20,000 people make up a relatively small percentage of the population, but can have an impact beyond their numbers.

“The financial costs to the city are not as big as the cost of the perception of the city, when people believe we have an unwarranted number of sex offenders,” Stokes said, noting the city is also home to Riverview Psychiatric Center, the state’s only hospital for people who have committed violent criminal acts but been deemed not responsible for their actions because of mental incompetence. “We understand that, as the capital city, we’re going to have some burdens other communities don’t have.

People in Augusta feel we’ve taken our share of the burden, and then some.”

Containment and stable housing

Sex offenders living in the city and contacted for this story declined comment. Most offenders on the registry have either unlisted or disconnected phone numbers. Efforts were made to reach out to offenders through probation officers, police, advocates, phone calls, in person visits and social media.

The Rev. Stan Moody, a former prison chaplain who still works with current and former inmates as they re-enter society, said most offenders, once they’re out of prison and have established themselves in the community, don’t want to bring up their past as a sex offender.

Gregoire said Detective Matt Clark spends at least every Tuesday and Thursday morning dealing with sex offender issues, such as updating the registry, and doing notifications to neighbors when a sex offender moves into their area.

Gregoire said city police do some type of notification whenever a sex offender moves into a neighborhood. How much notification they do depends on how much of a risk the sex offender is believed to pose.

Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty said the sheriff’s office overseas some 80 sex offenders in the rural areas of county. He says doing so takes staff time, in doing spot checks, fingerprinting, and processing records.

“But it’s a legitimate public safety issue, and we’re glad to do it,” Liberty said. “We try to keep them away from schools, playgrounds, those kinds of places.”

Landry said higher risk sex offenders released from prison are supervised by probation officers who specialize in sex offenders. They take what he calls a containment approach, involving a team made up of the probation officer, a sex offender therapist, law enforcement agencies and sometimes even the landlord of the offender.

“It’s a team approach to monitoring behaviors and ensuring accountability,” he said. “If they start to slip, it’s caught quickly.”

Moody said the corrections system has a “pretty well-oiled” system for helping inmates leaving prison find housing.

“It’s a very difficult situation for someone, coming out of prison, if you’re fortunate, you’ve got $60 and a bus ticket to Augusta,” said Moody, a former Manchester resident now living in the Bangor area. “Corrections will direct you to a landlord resource pretty quickly. They’ll point you to various sources of assistance. The question is, how good is the accommodation? A lot of these guys, they’re broke when they come out of there.”

Landry and Moody both noted one of the last things anyone — either sex offenders or the public — wants is for sex offenders to be homeless.

Landry said an offender with a stable living situation will be less likely to reoffend. He said prison case workers first look to the family of offenders to help support them as they leave prison, but often inmates don’t have family members there for them. Family members may have been alienated by the crime that put the inmate in prison.

The number of sex offenders in Augusta, while high, is trending down.

Stokes said some ten years ago Augusta had as many as 160 to 170 sex offenders.

In January, there were 134 registered sex offenders living in the city. Late that month, city councilors adopted a new sex offender residency restriction ordinance, which bans sex offenders who have committed acts against children younger than 14 from living within 750 feet of public and private schools and any municipal property, such as many parks, where children are the primary users.

However the ordinance is not retroactive, so sex offenders living in those restricted areas before the ordinance was adopted do not have to move elsewhere.

City Councilor Patrick Paradis said it’s too early to tell, for sure, if the ordinance is why the city has fewer sex offenders, who tend to be a transient population anyway, than it did before the ordinance was adopted.

“I think it was a factor, a real factor, in lowering the number of (sex offenders) looking at Augusta,” Paradis said. “I don’t know why we have as many as we do. But we’re very pleased the numbers have gone down.”

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

kedwards@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.