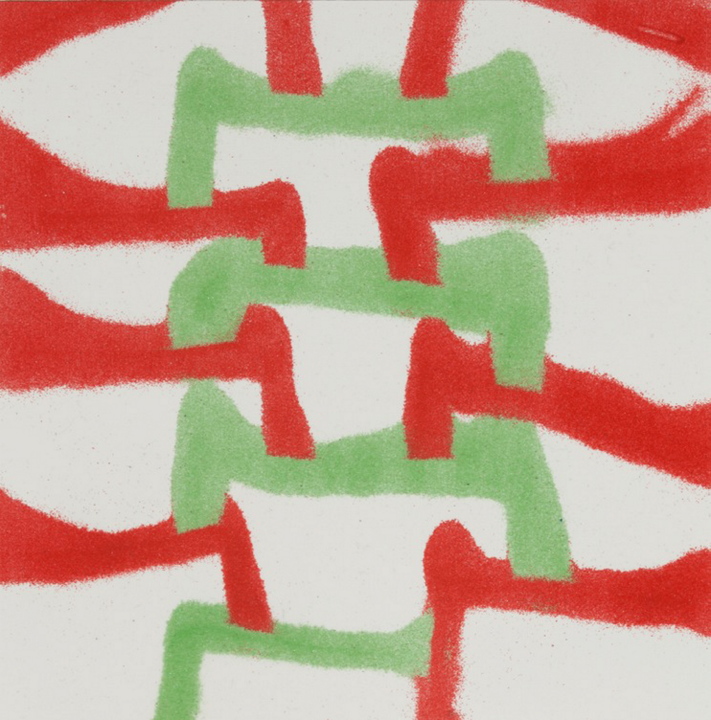

Cassie Jones makes upbeat paintings. Jovial, jocular and bouncy, they pop and zing. They look as though they would crackle with electricity if you run your hands over them.

Jones’s show at Aucociso features several dozen of her mostly intimate-scaled pieces (half of which were sold by or at the opening).

Jones makes paintings that are approachable and easy to enjoy – in part because they don’t require any explanation. In fact, they deny explanation: A few colors in clear, jaunty forms are easy enough to recognize as a painting that isn’t hiding anything from you. They are not veiled narratives or secret symbols or labyrinthine rebuses. Consequently, there are no barriers between the viewer and the work: It’s all right there in front of you.

But that doesn’t mean Jones’s work isn’t smart or doesn’t convey meaning – because it is and it does. Their intelligence lies in the space between “reference” and “elicit.” They set your mind moving as if you were at a dance rather than walking to the store.

When I first saw the piece in the gallery window, I thought “gumdrops.” I then thought of Dots (naked gumdrops that were a staple of ’70s movie-theater candy counters – now making a comeback) both because of texture and aesthetics. This was not the case of my parsing Jones’s references, but rather sifting through my own associations – which, while hardly triumphant, is fun.

The texture issue matters because the paintings in question are not made with brush and paint, but colored sand. The Dots/gumdrops distinction also brings up the retro aesthetics driving Jones’s painting.

Colored craft sand as paint is a fantastic tool in Jones’s hands – particularly if you are familiar with her previous work, and most notably her felt paintings (poofy, inflated and candy-colored wall pieces that look like balloon-animal paintings fresh off the set of “Yellow Submarine”). Familiarity with Jones’s previous bodies of work makes it clear she is taking her ideas and her sensibilities further and farther down the long and winding road. It is precisely not the student-quality zeal we so often see with encaustic newbies (“Look, encaustic!”) or watercolor rookies (“Look, I made an effect!”). Rather, changing media only makes it clearer that Jones has a vision and an unfakeable feel to her work.

The sand not only takes the brush out of the equation, but it removes texture as a variable, thereby unifying the image in one bold stroke. It also sets the conceptual clock a-ticking. The 29-inch-square “The Mix,” for example, features about 500 “dots” jumbled on the surface. While I went to “candy,” others, no doubt, will first think of a close-up of a Seurat painting, or a video screen, or marbles, or – ironically enough – bits of colored sand all jumbled together. And not only does Jones reach to the logic of pixilation, but she deftly juggles its representational (epistemological) and even philosophical (ontological) associations.

Is it stretch to pull Rationalist philosophy and, specifically, Gottfried Leibniz’s concept of monads, out of Jones’s Candyland-flavored hat?

Hardly.

First of all, Jones not only graduated from Bowdoin College – where I learned about Leibniz and other philosophers (thank you, Larry Lutchmansing!) – but she’s still very much attached to Bowdoin and its intellectual community.

Secondly, and more importantly, the ideas of Rationalism and “monadology” now pervade contemporary thinking about representation (pixelization, binary logic, etc), physics (String Theory, the “God” particle, etc.), as well as art (Pollack and the “allover” lack of figure/ground distinction, digital photography, game theory, and so on – the 2013 PMA Biennial is loaded with works pursuing such ideas: Kievett, Rogenes, Beck, Fensterstock, Bullitt, Cawley and many others).

Secondly, such a move moves away from the brush-like scripture of the pen and linear narrative notions (i.e. linguistic and causal) of explanation towards relational and systems approaches to understanding and representing the world. Sprinkling different colored sand is like cooking – balancing flavors, juxtaposing, mixing and so on. Rather than acting like an author, Jones is acting like a chef who pulls something delicious together for us from other people’s gardens as well as her own.

Clockwork and game theory mechanisms are more apparent in some works than others such as “By and Large” and “Over and Out,” which both rock back and forth on two-color systems like a pendulum – or a seesaw.

Jones’s retro aesthetic pulls in the idea of play, but also fabrics – and the way design rolls with the times. Any of these works (particularly the smallest ones) looks like a closeup photographic of fabrics (this makes the sand-as-pixelization idea feel like a home run), which in turn speaks to the cosmological qualities of the work, since fabric implies endless continuum mirrored in the macro- and microcosms of our universe.

Some viewers will see Navajo sand paintings. Others will think of Zen and Buddhist practices, beaches or things that have nothing to do with sand or granularity.

What we all are witnessing, however, is the emergence of an extraordinary contemporary artist.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.