If you are one of the many Dahlov Ipcar fans, don’t miss her show now on view at Frost Gully Gallery.

Ipcar is 96, but she is hardly hobbled artistically. Her hand as bold as ever and her work is getting more adventurous.

Ipcar has been a major artist for a long time: At the age of 21, she had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1939.

Not too many people can say that. In fact, no one else can.

But, like many famous artists who have been embraced by the general public, Ipcar’s fame is a double-edged sword. And both sides of that blade have been honed by her reputation as an illustrator of children’s books.

A colleague recently described a review of Ipcar’s 1979-80 retrospective at the Farnsworth: “The gist (…) was that Dahlov was not really a fine artist, that she illustrated children’s books and made stuffed animals.”

While that review resulted in a backlash tsunami of outrage, it raises important points. Still, such an assumption is a broken starting point for conversation and Ipcar has earned the right to be considered in depth. And I doubt that many will look closely at her work and come to that conclusion.

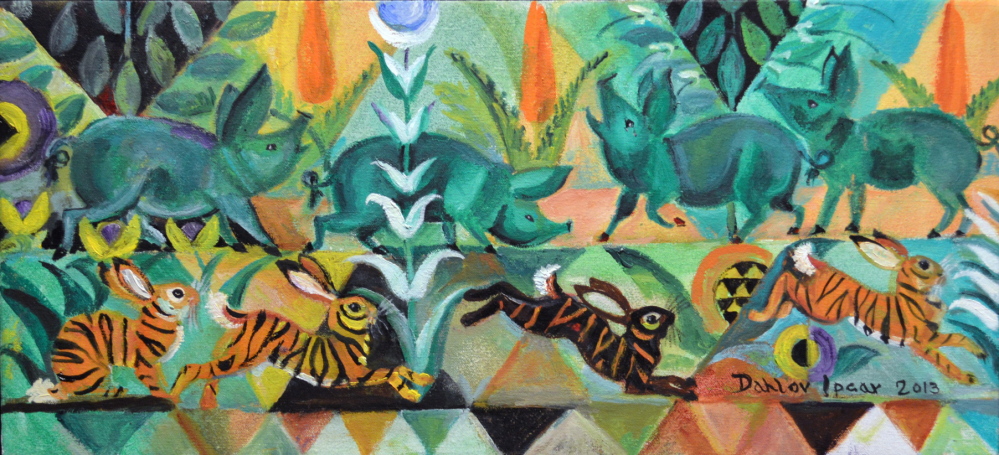

Ipcar’s best new work – and there are at least ten paintings from 2013 in the show – is deeply witty and playful. Moreover, she has taken up systems or even game theory logic that often appears by making exceptions to its own rules. One painting, for example, features green boars on a ground level tier visible above the foliage. Just below them folics a frieze of tiger bunnies – orange rabbits with black stripes. But one is black with orange stripes. While this brings to mind the old joke about the zebra questioning whether he is white with black stripes or black with white stripes, it raises this constellation of issues in an exceedingly approachable way and with an elegantly subtle sense of tolerance.

The painting’s title is “Mome Raths and Tiger Rabbits” – which ties it to Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poem “Jabberwocky” in Through the Looking Glass. Ipcar’s green boars are not the pre-packaged Disney products, but the surreal pigs from John Tenniel’s original illustrations. Strange and complex, this is hardly silly stuff.

Ipcar also introduces a heavy philosophical dose of Yin and Yang. This can be as playfully simple as a whirlwind pair of horses. But it can also be destabilizingly complex as in the playing card logic of “Equine Pinwheel.” Ipcar signed and dated it twice to make clear the alternate logic of the piece – which plays the static nature of painting (or the up/down form of playing cards) against the spinning logic of the title and the motion of the pictured horses.

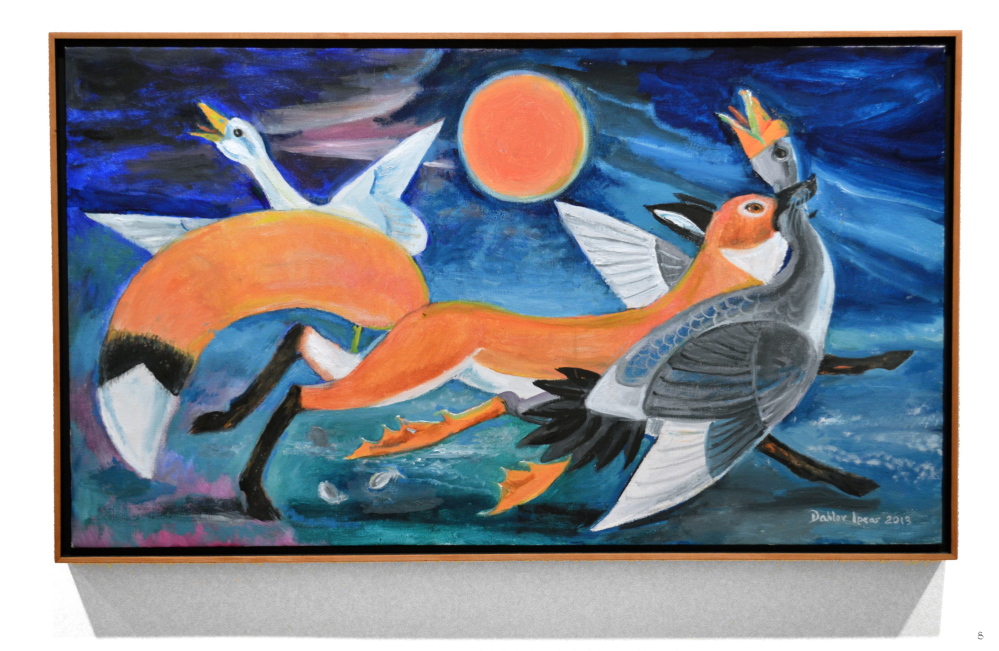

“The Fox Is on the Town” is strong enough to cleanse the show of animal innocence. Under a tangerine moon, a fox has seized a gander by the neck while his terror-stricken goose mate panics.

To compare Ipcar’s “Fox” to, say, Maurice Sendak – the great and beloved though controversial illustrator/artist – is to compare a grumpy child’s imaginative dream descent and return to a nighttime murder witnessed by the victim’s mate. Ipcar sees a brutal elegance in nature; and animalistic immorality is hardly a children’s tradition.

Yet, to recast the painting in Yin and Yang, we see the dangers of night, the cycle of life, male and female, predator and prey, husband and wife, and a food chain that even includes us.

A particularly interesting painting is “In the Greenwood” which shows two deer and two fawns in a grove center-punctuated by a leafless, black bolt of a tree. The structure of the landscape harkens to the diamond-oriented cubist format long favored by Ipcar (think Franz Marc). While one deer bends down over a light patch to graze, the two fawns prance. Yet, if that deer were not grazing contentedly, the over-the-shoulder “what was that?” gaze of the deer on the left would imply danger – and so the fawns would be seen as fleeing. The left deer, as well, is standing in a night patch; and this is one of Ipcar’s most elegant set plays. Darkness doesn’t settle in shades of gray, but creeps in patch by patch. The greenwood, in other words, is in both night and day; and each mode has its qualities.

A few other particularly interestingly works include a blush-worthy pair of tigers indulging in watermelon; the spiritually charged “Sacred Grove” featuring a dazzling white stag; the hysterically raucous “Farm Ruckus” and the mystical, paired-animal arc adventure “Arrival” with its zooming crystal bridge dimensionally marked by a zebra brilliantly rendered in three-quarter pose.

While I would say her brush is better than ever, Ipcar’s unironically straightforward paintings don’t hold my interest and they never have. While I understand why some people can’t accept anything that looks like illustration is serious art, I think introducing children to intelligently thoughtful painting and making that work available anywhere there is a library is a practice to be commended rather than condemned.

Ipcar is a heavily stylized painter, so if you don’t happen to like her style or palette, there is a lot to not like. But sometime in the last 20 years, I came around to like Ipcar’s paintings; and this show makes a strong case that the painter from Georgetown is not just a famous Mainer, but a great American artist.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.