Part two of a two-part series

Every year, the state shares some of the money it collects in taxes with Maine’s schools and cities and towns to help them pay their bills and keep property taxes under control.

Which communities get how much is determined by a formula that includes the size of the town and the total value of its real estate. After population is taken into consideration, the richer the town – richer in terms of total property values – the less it gets in state aid. The poorer, the more it gets.

But there’s a big exception to this rule – an exception that lets some richer municipalities and school districts look poorer than they really are and get more money from the state.

That exception is called tax increment financing, or TIF.

Communities that make TIF agreements with local businesses can effectively hide the value of a new building put up by those businesses. A business in Town X, for example, may put up a $1 million building, but as far as the state is concerned, when it comes to sending out state aid checks, if there’s a TIF, Town X is no richer than it ever was and its state aid is not affected.

Because the pool of state aid is finite, if one town gets more state aid because of a TIF sheltering agreement, that means a town without a TIF or with smaller TIFs will get less state aid.

The concept behind the sheltering of the new valuation is to encourage towns to give tax breaks to local businesses by not punishing growth with a smaller state aid check.

And that’s just a secondary part of the state TIF law. The primary part of the law allows local governments to divert property taxes paid by businesses granted a TIF. Instead of going to pay for the town’s usual expenses, taxes paid by a business with a TIF are used to build infrastructure in the town or even given back to the business.

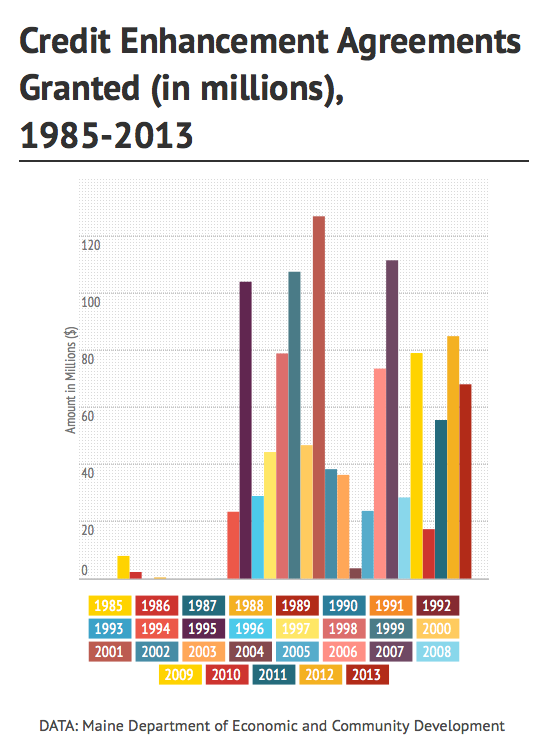

Since 1985, the total value of these tax diversions granted by cities and towns is nearly $2.8 billion, according to state records that are based on reports from municipalities.

Used originally to promote development in blighted areas, TIFs are increasingly being used by towns as a method to protect their share of state aid.

A little-understood provision in state law allows towns with TIFs to legally short their fellow Mainers. The provision was added to the 1977 TIF law in the 1980s and allows towns to keep increased real estate value sheltered from the state for up to 30 years when it’s in a TIF district.

TIFs also allow cities and towns to hide new valuation from the county tax collector – meaning they won’t have to pay more taxes to the county for services such as jails.

So towns are motivated to establish TIFs because the math works in their favor, said Shana Cook Mueller, an attorney at Bernstein Shur who helps towns package TIFs.

“For every new tax dollar that you receive in that municipality,” said Mueller, “you lose some percentage of that, usually between 30 and 70 percent” in state aid, unless the new tax dollar is sheltered with a TIF.

Peter Nielsen, Oakland’s city manager and the president of the Maine Municipal Association, describes the phenomenon with a metaphor.

“We’re trying not to pay taxes on our raise,” he said to explain how the scheme works. “We want to get the whole $100 raise without paying the $20 in taxes.”

The $2.7 billion in TIFs granted between 1985 and 2013 by Maine towns will allow those towns over the life of the TIFs to get between $810 million and $1.9 billion more in state revenue sharing, aid to education and lower county tax payments than they would have without the TIF, based on the percentages estimated by Cook Mueller.

Conversely, since the pot of revenue sharing and aid to education is finite, it means non-TIF towns get that much less in state aid and will also have to pay higher county taxes.

TIF critic Orlando Delogu, a University of Maine law professor, said he wonders constantly “why non-TIF-granting municipalities aren’t up in arms over this unfairness.”

TIFS TURNED ON THEIR HEAD

There’s a burgeoning industry among lawyers and consultants in Maine to promote TIFs as a way to pay for city-initiated projects and avoid the punishment of diminished state aid and increased county taxes.

It’s a beggar-thy-neighbor practice that turns the traditional TIF model on its head. Instead of developers who need a tax break, it’s tax breaks that need a developer.

“Years ago,” said Nielsen, “the purpose of the TIF was to build town infrastructure, lights, sewer, etc., to benefit the company” developing the property.

“That seems to have faded from prominence,” he said. “So now we talk about what sorts of economic development projects can we do that will make it under the wire with the state” and get TIF approval.

“The game is to construct a list of activities for the use of tax dollars that is as much in line with local priorities as possible and not be unduly restricted as a result of having put a TIF in place,” said Nielsen.

That perspective is mirrored in an informational presentation on TIFs on the website of law and consulting firm Eaton Peabody.

“…(C)apturing the new assessed value in a TIF district provides benefits for communities by creating a new revenue stream for eligible community projects, while avoiding an increase in costs to the community that could occur from a new business development project,” wrote John Holden and Jon Pottle, who work for Eaton Peabody.

The net result, according to Holden and Pottle: “Money stays local, helping to support and grow the local economy.”

The shorthand for what is happening is “tax shifting.”

The response by TIF proponents to the “tax shifting” charge is that any town can do a TIF. But it’s mostly urban towns or mill towns that have TIFs in Maine — thus shifting the tax burden mostly to rural communities.

“You’re not going to have a TIF unless you have some sort of major economic development project,” said Jonathan Block, an attorney who works on TIFs at Portland law firm Pierce Atwood. “You wouldn’t have a TIF in the middle of the woods or in an agricultural community because there’s nothing to TIF. You wouldn’t have it for a very small business because the cost of doing it is not worth it.”

And complex TIF deals are difficult to put together if you’re a small town with little or no staff.

There’s another unfairness acknowledged even by town managers who have created TIFs. When Nielsen was Wilton’s town manager, a national chain wanted a TIF to help it open a motel in the town.

“A couple of motel owners in town said, ‘Why should my tax money be incenting my competition? I built my business the hard way and nobody gave me any help and you want me to be supportive of bringing a major competitor into my world,’” said Nielsen.

“It has to give pause to anyone,” he added, “why do some businesses get support and others do not?”

Similarly, the tax breaks given to business through TIFs aren’t available at all to the bulk of local property taxpayers – the homeowners.

When Bath Iron Works asked the city of Bath for a multimillion dollar credit enhancement TIF last fall, town resident Gary Anderson was quoted in the The Forecaster as calling the TIF “an arrangement which other property owners are not offered. When a person renovates their home, there is no partnership with the city that returns half of their increased property taxes.”

EXPERTS DOUBT TIFS

While businesses and state and local economic development officials assert the virtues of TIFs, there’s scant data to support claims that TIFs have a positive effect on property values, economic activity or jobs.

The academics who study TIFs are pretty clear: While TIFs may be politically popular, they’re economically questionable.

Columbia law professor Richard Briffault wrote in the Chicago Law Review in 2010: “TIF brings in no outside money and provides no new revenue raising authority. There is little clear evidence that TIF has done much to help the municipalities that use it, and it is also a source of intergovernmental tension and a site of conflict over the scope of public aid to the private sector.”

A 2006 study by David Merriman and Richard F. Dye of the University of Illinois concluded that “any growth in the TIF district is offset by declines elsewhere” and that “property value in TIF-adopting municipalities grew at the same rate as or even less rapidly than in non-adopting municipalities.”

Marc Cryer, director of the University of Maine’s Bureau of Labor Education, said he’s not aware of any data that shows TIFs improve local economies or increase jobs in Maine.

“If someone tells you that they have solid numbers that prove that TIFs work to the advantage of the communities they are in, we don’t have them,” he said.

And a 2000 report by the state’s short-lived Economic Development Incentive Commission stated that University of Maine economist Todd M. Gabe found that “there is not a statistically significant relationship between employment growth and an establishment’s participation in the TIF program, all other things being equal.”

Despite the lack of scholarly evidence that they work, TIFs are in no danger of being eliminated in Maine. Since their inception, legislation affecting TIFs has only expanded their use, most recently in 2013. They enjoy the support of Maine’s influential business community and the Maine Municipal Association, the professional and lobbying group that represents most cities and towns in the state.

And lawmakers have shown no appetite for cutting back any of the state’s dozens of economic development programs, most of them some sort of tax break for businesses.

After promising last year to try to cut $40 million in business tax incentives to fill a budget hole, the legislature’s Tax Expenditure Review Task Force was unable to recommend which programs to eliminate or even cut back.

TIF critic Delogu said he knows why no one has ever mounted a serious effort to curb TIFs.

Legislators “haven’t the courage to take on the vested corporate interests,” he said.

Former legislator Peter Mills, a Republican from the rural town of Cornville, said, “Because it doesn’t do the state any biennial (budget) harm … it doesn’t crop up as something to fix.”

In the end, Mills said that TIFs will persist in Maine largely because no one outside of a small circle of attorneys and town development officials understands them well enough to do anything about them.

“That’s the evil of this,” Mills said. “Does anyone think there are more than 10 legislators who understand how TIFs work? Any more than five of them who really care?”

The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service based in Hallowell. Email: mainecenter@gmail.com.

Web: pinetreewatchdog.org.

This series was edited by John Christie, the Center’s editor-in-chief.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.