Researchers who conducted tests have known for at least eight years that lobsters at the mouth of the Penobscot River contained “hazardous” levels of mercury, but consumers were not told until the state announced it this week.

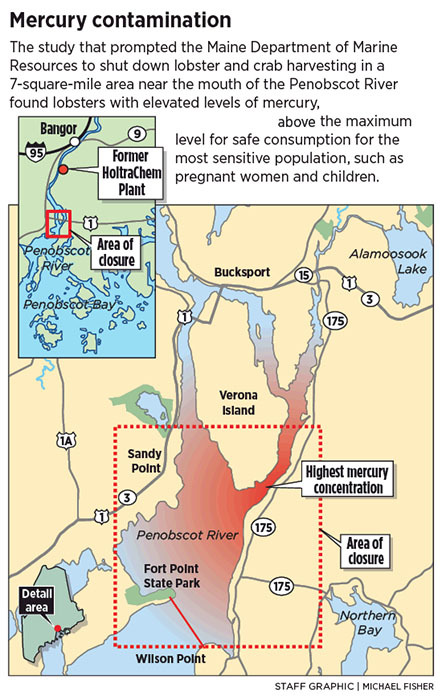

The long-term study that led the Department of Marine Resources to declare Tuesday that it will close down lobster and crab harvesting in a 7-square-mile area shows that lobsters in the area have had mercury levels, year-to-year since 2006, that are higher than the state deems safe to consume.

The banks downriver from the former HoltraChem Manufacturing Co. plant in Orrington still contain mercury, decades after the company stopped dumping chemicals into the waterway leading to the bay, according to the study.

The study, first ordered by a federal judge in 2003 and completed by a team of three scientists in 2013, says that mercury contamination in the sediment and wetlands has been declining slowly since HoltraChem began discharging mercury waste directly into the river in 1967, but is “still high enough to be hazardous” to plants and animals and the people who eat them.

The revelation about contaminated lobsters is a black eye to the state’s most valuable fishery, which has endured low prices in recent years. But the closure of the area where the river empties into Penobscot Bay applies to only a small fraction of the more than 14,000 square miles in the Gulf of Maine where lobsters are harvested.

State Toxicologist Andrew Smith, who was called in to analyze the study’s findings after they were first shared with the Department of Marine Resources in November, said lobsters from that small area had high mercury levels, but most lobsters caught along Maine’s coast have less than half the amount of mercury contained in canned chunk light tuna, and less than one-sixth the mercury of canned white tuna.

“Really, people should have no worries about eating lobster,” Smith said. “They should be looking at it as a seafood (with mercury levels) well below what they typically consume.”

Mercury is toxic to humans and, in high doses, can attack organs and neurological systems such as the brain, peripheral nerves, the pancreas, the immune system and kidneys. Unborn children are especially sensitive to mercury’s toxic effects, and excessive exposure can lead to mental disabilities, cerebral palsy and nervous system damage.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention has advised that pregnant and nursing women and children younger than 8 eat no more than 8 ounces of fish per week, based on guidelines that estimate a safe level for consumption at 200 nanograms of mercury per gram of meat. Two average-size lobsters yield about 8 ounces of meat.

STUDY FINDINGS SLOW TO COME OUT

The court-ordered study stemmed from a lawsuit brought in U.S. District Court in Bangor against HoltraChem, which is now defunct, and its inheritor, St. Louis-based Mallinckrodt Inc., by the Maine People’s Alliance and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Those groups sought to hold the chemical producer liable for its pollution of the Penobscot River and Penobscot Bay. The lawsuit has been ongoing since 2000, when the HoltraChem plant in Orrington closed.

After a trial in 2002 in which Mallinckrodt was found responsible for the pollution, Judge Gene Carter, who is now retired, ordered the formation of the study panel. The study’s findings will be used in a second trial in the same case, scheduled to start in May, to determine what Mallinckrodt must do to clean up the damage to the federally protected waters.

By the 1980s, HoltraChem had created five secure landfills on the site of its plant to contain mercury brine sludge. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection has since ordered Mallinckrodt to complete a $250 million cleanup of the site, a decision that Mallinckrodt appealed to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. The court heard oral arguments in that appeal last week and has not said when it will rule.

Smith said he and DEP staff members began receiving data from the study in November, and discovered in requesting additional information that mercury contamination in lobsters in the 7-square-mile area had remained consistently high in individual lobster samplings from 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2012.

“This is really our first involvement in looking at this data and investigating this data as far as lobsters go,” Smith said Wednesday.

It is unclear whether any government agency was notified in the years after the court-ordered Penobscot River Mercury Study Panel made its discoveries.

The Department of Marine Resources says it wasn’t notified of the findings for at least six months after the panel filed its final report in federal court, in April 2013.

Cynthia Mehnert, an attorney who represents the Maine People’s Alliance in the state and federal lawsuits, said the alliance and the Natural Resources Defense Council forwarded the study results to the Department of Marine Resources so the state would have the information. It’s not clear why the department did not receive them until November.

“Certain homeowners who live close to the plant site take regular samples from their wells. A certain number of people in the area have not been eating shellfish for some time,” Mehnert said. “I think the surprise was that we thought it was bad, and it’s really much worse than we thought.”

She said the alliance is chiefly concerned that one of the five landfills on the former chemical plant site is close to the banks of the Penobscot River.

“You can see the erosion of the banks is making Landfill 1 closer and closer to the river. If that were to erode into the river, that would be a mess,” she said.

DIFFERENT RESULTS IN OTHER STUDIES

Smith said “there’s a big difference” between the data from the court-ordered study and past data on contamination that was collected by state and federal agencies.

The Maine DEP, in conjunction with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, studies ambient toxicity levels along the Maine coast every five years. Those studies are not as precise as the court-ordered study of the Penobscot River, said Jim Stahlnecker, a DEP biologist who oversees the state’s marine monitoring program.

The DEP’s most recent coastal study, in 2010, did not take samples from the upper part of Penobscot Bay where elevated levels of mercury were found in the court-ordered study, Stahlnecker said.

Sample sites for the coastal studies are chosen at random, not by proximity to potential sources of pollution, he said.

The level of mercury found in lobsters in the area that will close on Saturday is similar to that in canned white tuna, said Jeff Nichols, spokesman for the Department of Marine Resources. He said Commissioner Patrick Keliher could have allowed harvesting to continue in the area while issuing an advisory similar to that for white tuna, which calls for children and pregnant and nursing women to eat no more than 6 ounces in a week.

Instead, Keliher decided to close the 7-square-mile area for two years and continue monitoring the area and adjacent areas, Nichols said.

“The commissioner decided to take a more conservative approach and act to protect public health and assure consumers they can be confident that eating Maine lobster is safe,” Nichols said.

He said the department is not certain that the source of the mercury is the HoltraChem plant. “I can’t point to a specific source of mercury in this area,” he said.

MORE TESTING SET IN CLOSED AREA

The Department of Marine Resources will test this spring for mercury levels in lobsters and crabs in the area and adjacent areas, using the same methodology of the court-ordered study, said Carl Wilson, the department’s lead lobster biologist.

He said the department tentatively plans to conduct the study every quarter during the closure. The adjacent areas to be studied include the Isleboro, Castine and Belfast areas, he said.

Nichols said lobsters, particularly large ones, have been known to travel hundreds of miles. Maine lobsters have been found in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia and on Georges Bank, he said.

Generally, about a third of lobsters remain in one place, a third migrate fairly short distances to deeper water in winter, and a third travel long distances.

He said larger lobsters travel farther because they have longer legs and are more capable of crawling greater distances.

There is some evidence that mercury levels decline over time after lobsters move away from the source of contamination, Wilson said.

“If a lobster leaves the area, it doesn’t carry the same level of mercury wherever it goes,” Wilson said.

He said annual monitoring in multiple locations along the Maine coast shows that lobsters outside the closed area are safe to eat.

Scott Dolan can be contacted at 791-6304 or at:

Twitter: @scottddolan

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.