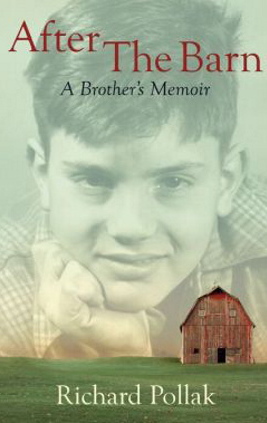

Richard Pollak’s “After the Barn: A Brother’s Memoir” turns around an event that happened in a hayloft in Cassopolis, Mich., when he was 14 and on vacation from Chicago with his family. He and his brother Stephen, 11, were playing hide-and-seek in the hay. His brother fell through a hole in the loft and plummeted 30 feet to his death.

His brother had been on a home visit from the Orthogenic School for mentally disturbed children, against the advice of noted psychiatrist Dr. Bruno Bettelheim, who ran the school.

Though Pollak was discouraged from talking of his brother’s death by “a tomb of silence” within his family, he lived with the burden of guilt for his brother’s death for 50 years. He came in time to feel that he was like his brother, “mentally deficient,” for Pollak experienced his first epileptic seizure only months later, something his father told him he shouldn’t talk about, as it was nobody’s business – like his brother’s troubling behavior and death.

Pollak went on to become a journalist and a writer, working as executive editor of The Nation, and at Newsweek. He also wrote for Harper’s, The Atlantic and The New York Times Book Review. He also wrote several books, including, among others: “Up Against Apartheid: the Role and Plight of the Press in South Africa,” “The Episode,” a novel that deals with epilepsy, and “The Creation of Dr. B: a Biography of Bruno Bettelheim,” an expose detailing Bettelheim’s false credentials, plagiarism and cruelty to children under his care. The Washington Post and The New York Times praised it.

All the while, he felt a compulsion to write of his brother’s death. He started on it in the 1980s; put it aside; later picking it up again – and again putting it aside.

Pollak is married to noted pianist Diane Walsh. While at Julliard, Walsh won the prestigious Van Cliburn competition in chamber music. She has performed all over the world, including Vienna, Munich and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. Pollak called New York City home for nearly 50 years, but in January he and Walsh moved to Portland, after considering several other cities, including some they visited during an around-the-world trip. They make their home on Munjoy Hill.

Q: You started writing this memoir over 30 years ago, did research, had false starts. You had publishers interested in it. What made it possible to finally take it on and see it through?

A: I think something inside of me clicked.

I had written some very demanding books by that time. I’m very proud of “Dr. B.” It was very special to me. I felt a confidence after doing it, and in doing “The Colombo Bay,” that I hadn’t had before.

The other part was that Diane kept saying, “Do it. Stop talking about it and do it.” I finally got a manuscript that I liked. But by that time, editors didn’t care. So I published it myself.

This book isn’t about money. It’s something that I’ve wanted to write for years.

Q: There’s a riveting, deeply haunting line early in the book. You’re at the barn, and your parents are ready to go, but your brother won’t stop hiding. And you say to your parents, “Tell him you’ll punish him if he doesn’t stop hiding.” There was a rustle in the hay, and then Stephen fell to his death.

A: I felt tremendous guilt about it for years. I’d seen a psychiatrist, but it wasn’t until I saw Shelley Robin (doctor of psychology), and she said that that was a perfectly normal thing for a 14-year old boy to say to his 11-year-old brother. Nobody had ever said that to me. It was an epiphany, a cathartic moment.

I don’t know if that re-energized me about the book, but it certainly lifted a huge burden of guilt that I’d been carrying for years.

Q: You write about false memories you had about the incident.

A: They weren’t false memories. They were scenarios that I made up in the absence of any real memory. That there must have been a trooper there. There must have been an ambulance. That my father must have shielded me from seeing my brother.

Years later when I went back to Cassopolis, back to the barn, I naively thought it would trigger real memories. But it was like going to a place I’d never been to before. I had thought that Cassopolis was my Lourdes. That the barn was my healing grotto. But it wasn’t. I couldn’t throw away the crutches.

Q: Years before you wrote “Dr. B,” you interviewed Dr. Bettelheim, hoping to fill in the gaps around Stephen’s death. But he made you swear not to share a word of it with your parents. You also write in the book that your parents never spoke of your brother’s death, that you grew up in a “tomb of silence.” Did these twin bookends of secrecy make it difficult for you to tell the story?

A: Bettelheim’s demand was aimed at my parents. He didn’t want me to reveal to them what he said. I made the deal because I thought if I said no, he’d throw me out. The other bookend, my parents – it wasn’t about them. It was generational. These things were buried, like the Kennedys putting their daughter in an institution. These things were a shameful embarrassment.

Q: Dr. Bettelheim said that your mother was to blame for your brother’s problems – which fit his theory about autism and other childhood mental, behavioral problems. You said in your book that he referred to the mothers of his patients as “refrigerator moms.” I was struck by one line he angrily said to you: “What is it about these Jewish mothers?”

A: I was seeing him 20 years after Stephen’s death, but for him, it was like it happened yesterday. I was shocked by his anger, his rage.

Here was a guy who had spent time in the camps during the war, in Dachau and Buchenwald. He’d had everything taken away from him, his whole life in Vienna.

I was 30 years old, a journalist. I had done a lot of interviews, covered the civil rights movement in the South. Yet I was reeling from what he said. I couldn’t say anything. I had come to talk about something very sensitive, and he told me that my parents were monsters.

Q: How does it feel to finally have gotten this story out?

A: The reaction to the book has been quite positive. It is very satisfying to have people who’ve experienced something similar, but don’t have the skills to tell their stories, to have them tell me that reading it helped them.

Q: After nearly 50 years as a New Yorker, how do you like living in Portland?

A: Both Diane and I really like it here. I love the air, the snow. Neighbors tell us this winter has been particularly harsh. But I’m a Chicago boy – and I like it. When you go out in the morning, and it’s bracing and bright, and you walk up to get coffee and a bun. It’s magical.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” a finalist for the Bellwether Prize, will be published as a trade paperback in the spring. He can reached via:

www.thewritinggroup.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.