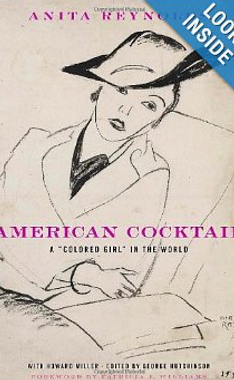

Anita Thompson Dickinson Reynolds was the black – or mocha – Zelig, traipsing continents at will, dancing on Broadway, acting in Hollywood with Rudolph Valentino, toiling as a journalist during the Spanish Civil War, slumming it with French royalty – all the while rubbing shoulders with the likes of Coco Chanel, Ernest Hemingway, Charlie Chaplin and W.E.B. Du Bois.

As Reynolds recounted in her recently discovered memoir, “American Cocktail: A ‘Colored Girl’ in the World,” she had adventures. Oh, did she have adventures. Reynolds had a knack for getting herself entangled in key moments of early 20th-century history: There she is, in Harlem in the ’20s, a “jazz baby” hanging out with artists of the Harlem Renaissance. There she is in the ’30s, partying with Picasso in Paris. (Matisse sketched her, too.) In the ’40s, you could find her working for the French Red Cross, scrambling to help Jewish refugees as Nazi planes fly over France. And finally, you could find her in Lisbon, hopping the last thing smoking out of Europe.

“I was an asteroid then, in orbit around the brilliant stars,” wrote Reynolds, who later became a psychologist. “Perhaps some of their genius would rub off on me.”

Actually, Reynolds’ genius was in her ability to blend in and ingratiate herself with some of the world’s most powerful. Reynolds thought she deserved to experience what the world had to offer – and she went for it at a time when few black women were able to escape the confines of skin color. Of course, looking like a generic ethnicity helped.

A self-described “American cocktail,” Reynolds was born in Chicago at the turn of the century to a well-to-do mixed-race family and raised in Los Angeles. No one would mistake her for white, as they did with her blond mother, but they certainly mistook her for plenty of other things: Mexican, South Asian, American Indian.

Most of the time she didn’t bother to correct them. The confluence of skin color and class worked to her advantage – and so, she took advantage.

Call it the audacity of audacity.

Beyond her charmed circle, not many knew of Reynolds. In the late ’70s, she figured she should chronicle her incredible life. But publishers weren’t interested in her autobiography, which she co-wrote with Howard Miller. She died in 1980, and for a while, her story died with her – until Cornell University scholar George Hutchinson found her unpublished papers in Howard University’s archives. Working with photos, original manuscripts and Reynolds’ scribbled notes, Hutchinson resurrected her memoir. The result is a fascinating, and sometimes maddeningly conflicted, account of an apolitical party girl who was pro-royalty, pro-sex and (sometimes) pro-black.

“I was not reminded of the horrors of American lynching every day, nor did I care to be,” she wrote of her time in Europe. “One must feel deeply to want to write about these things, but at the time, I wanted to be living a light, gay way, not feeling deeply about much of anything.”

She grew up in a politically active family in Los Angeles. But early on, Reynolds chafed at the constraints of the black bourgeoisie. “Most of their gatherings were prim, decorous and rather formal, members of a minority group trying to outdo the majority by behaving ‘properly,’ ” she wrote. Reynolds wanted none of that, and she grabbed life by the neck and shook it hard, taking money her dad had sent her for college and running off to Paris, Morocco, London and Spain, acquiring a British accent along the way – and generally confusing anyone who encountered her.

“How long did it take you to get that wonderful suntan?” a German tourist asked her. Her response: “About four generations.”

Through Reynolds’ eyes, we see that race was a fluid thing, something to be shrugged on and off as she saw fit. Reading her memoirs, it’s hard to fault Reynolds for the choices she made, given the hand she was dealt.

Still, reading her breathless prose, it’s easy to feel frustrated at her willful refusal to plumb any emotional depths.

Then again, perhaps living the way she did, laughing the whole time, was itself a revolutionary act.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.