The widow of the Windham man who was fatally shot by a Cumberland County sheriff’s deputy Saturday says her husband did not point his gun or wave it just before he was shot in the head, her attorney said Tuesday.

Instead, Stephen McKenney, 66, a retired bus driver who was haunted by chronic back pain, kept his hands at his sides, Vicki McKenney told her lawyer, Daniel Lilley.

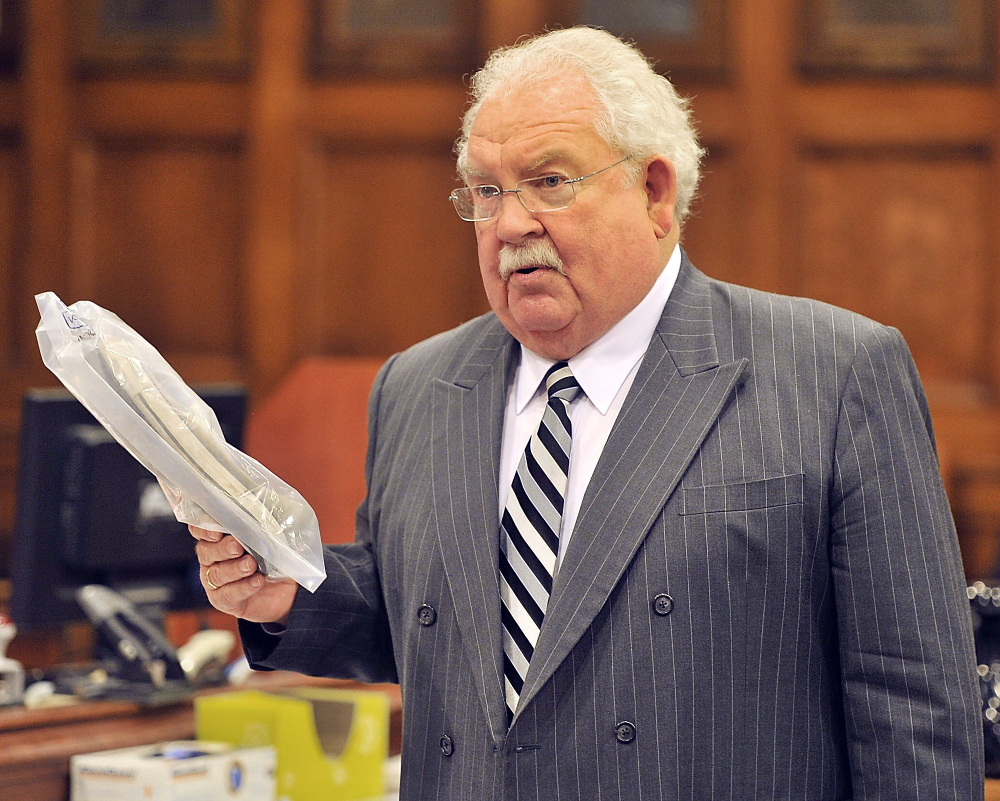

“She’s absolutely certain his hands remained at his sides at all times until he fell to the ground,” Lilley told the Portland Press Herald on Tuesday. “She saw no hands or no guns pointing at anybody.”

Police were called to 2 Searsport Way at 6:14 a.m. Saturday for a potentially suicidal man. Two Windham officers and Sheriff’s Deputy Nicholas Mangino responded. They got McKenney’s wife out of the house and, a short time later, McKenney came out of his garage.

Police said he was he was holding a gun and the officers repeatedly ordered him to drop it, which he refused to do.

Sheriff Kevin Joyce said he was told that Mangino fired after McKenney pointed his gun. Police said at one point that McKenney was waving the gun.

Mangino fired two shots, one of which hit McKenney in the head.

Joyce said Lilley’s account differs from the way he was told the incident unfolded. He said the details will become public once the state Attorney General’s Office completes its required investigation.

The Attorney General’s Office is investigating to determine whether Mangino’s use of deadly force was justified. To be justified, an officer must reasonably believe that he or she, or another party, faces immediate danger of serious injury or death, and that deadly force is necessary to end the threat.

Such investigations can take as little as 30 days or as long as three months.

McKenney had been suffering from constant and severe pain since he hurt his back while helping a neighbor move an air conditioner in September, Lilley said. The pain kept him from sleeping, even though he was taking medications for the pain.

He had been to Mercy Hospital’s emergency room because the pain was so acute, and he had appointments scheduled with specialists this week to try to diagnose and correct the problem, Lilley said.

Vicki McKenney called police Saturday morning to say that her husband “may be suicidal,” Lilley said. She did not tell police at that point that he had a gun.

Lilley said he did not believe that McKenney had any mental illness, and he had not been drinking.

When officers arrived, they met with Vicki McKenney. Police asked if her husband had any guns in the house. She said that he did, that he was a gun collector.

McKenney kept one gun loaded in the house, a .357 magnum that had a full load of bullets but not one in the chamber, Lilley said. A round is chambered in that gun when the hammer is pulled back, he said.

McKenney kept it in a holster hanging from a bedpost. It was not on a belt, Lilley said.

After officers determined that McKenney had access to guns, they moved his wife to a cruiser and apparently moved the cruiser about 75 yards down the road, Lilley said. She was in the back seat, watching, with the car facing the house.

“She said she was just focused on him like a laser – because she was so scared – and she was screaming off and on for them to Taser him, don’t shoot him,” Lilley said. She doesn’t know if anyone could hear her, he said.

She saw her husband leave the garage and walk almost to the end of the driveway, Lilley said. “She saw his hands by his side. She did not see the gun,” he said.

Vicki McKenney said she did not see the deputy, who may have been partially hidden from her by a cruiser, Lilley said. Later, she estimated the officer was 20 feet from her husband when he fired a shot.

“She said that she saw the dirt behind him or near him in some fashion, as if a bullet had hit something and caused material to rise. She assumes it’s the first shot. If that’s true, it would appear the first shot hit ground and not him,” Lilley said. “She did see that before he dropped.”

Lilley said the orientation of the cruiser means it’s possible the incident was caught on video in the cruiser.

Sheriff Joyce said the county’s cruiser does not have dashboard video. Some Windham cruisers do and others don’t, he said.

If McKenney did not make a threatening gesture with his gun, Lilley said, then he should not have been shot. He said McKenney’s widow is not vindictive toward police but wants to make sure such an incident does not get repeated.

“It doesn’t appear, from what she saw, he was doing anything illegal,” Lilley said. “From this eyewitness, the answer is no, there didn’t seem to be any justification for shooting. If there’s another story or a videotape somebody has, then it’s a question of credibility.”

Lilley questioned whether Mangino, a deputy who graduated from the Maine Criminal Justice Academy at the end of 2012, had the necessary training and experience for the situation at the McKenneys’ home.

Mangino has completed the 40-hour crisis intervention team training, which helps officers recognize and deal with people in mental health crisis. According to Joyce, there was little time to use such training in Saturday’s incident. The time from the initial call to when McKenney was shot was just 17 minutes, he said.

If McKenney didn’t raise his gun to point it or wave it, the assessment of whether police had to shoot him will depend on other factors, said Melvin Tucker, a former police chief who is an expert in officer-involved shootings.

Now based in Raleigh, N.C., he worked for the Maine Community Policing Institute and has been an expert witness for state prosecutors and plaintiffs, as well as an instructor in use of force.

Tucker said officers are taught to contain the threat when they approach a potentially dangerous person, control the scene so no one else enters the area, and communicate with the suspect from a position where the officer is protected from bullets or can’t be seen.

The degree to which they do those things can determine whether they are in immediate danger, and whether deadly force is justified, he said.

Even if a person doesn’t point a gun, but refuses commands to drop it while the officer or someone else is exposed, an officer may be justified in shooting, Tucker said. A person can raise a gun and fire in a fraction of a second.

“You don’t have to wait for the glisten of steel or sound of gunshot to defend yourself,” he said. “It would be too late if you waited.”

The Maine Attorney General’s Office has reviewed more than 100 cases of officers using deadly force since the reviews became required in 1995. It has found the officer justified in every case.

Tucker said that may have more to do with what the Attorney General’s Office is assessing and the nature of police training than any bias toward police.

“The laws are pretty much favorable toward the law enforcement officer … both civilly and criminally. You’re talking about defense of life,” he said.

The AG’s Office does not evaluate whether officers could have handled situations differently or avoided confrontations. It looks only at the moment the shots were fired: whether the officer believed that he or she or someone else was seriously threatened.

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@pressherald.com

Twitter: @Mainehenchman

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.