NEW YORK — Before “The Simpsons” or even “The Daily Show,” Al Feldstein showed America how to laugh at itself and giggle at popular culture.

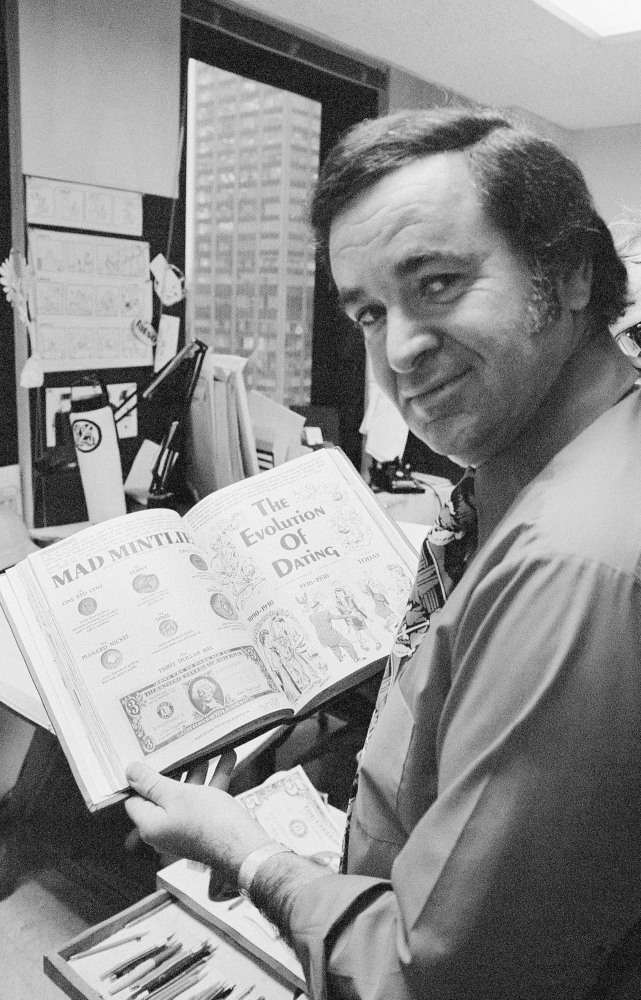

Millions of young baby boomers looked forward to that day when the new issue of Mad magazine, which Feldstein ran for 28 years, arrived in the mail or on newsstands. Thanks in part to Feldstein, who died Tuesday at his home in Montana at age 88, comics were more than escapes into alternate worlds of superheroes and clean-cut children. They were a funhouse tour of current events and the latest crazes.

“Basically everyone who was young between 1955 and 1975 read Mad, and that’s where your sense of humor came from,” producer Bill Oakley of “The Simpsons” later explained, citing “The Simpsons” as a worthy successor.

Feldstein’s reign at Mad, which began in 1956, was historic and unplanned. Publisher William M. Gaines had started Mad as a comic book four years earlier and converted it to a magazine to avoid the restrictions of the then-Comics Code and to convince founding editor Harvey Kurtzman to stay on. But Kurtzman soon departed anyway and Gaines picked Feldstein as his replacement.

One of Feldstein’s smartest moves was to build on a character used by Kurtzman. Feldstein turned the freckle-faced Alfred E. Neuman into an underground hero – a dimwitted everyman with a gap-toothed smile and the recurring stock phrase, “What, Me Worry?” Neuman’s character was used to skewer any and all, from Santa Claus to Darth Vader, and more recently in editorial cartoonists’ parodies of President George W. Bush, notably a cover image The Nation that ran soon after Bush’s election in 2000 and was captioned “Worry.”

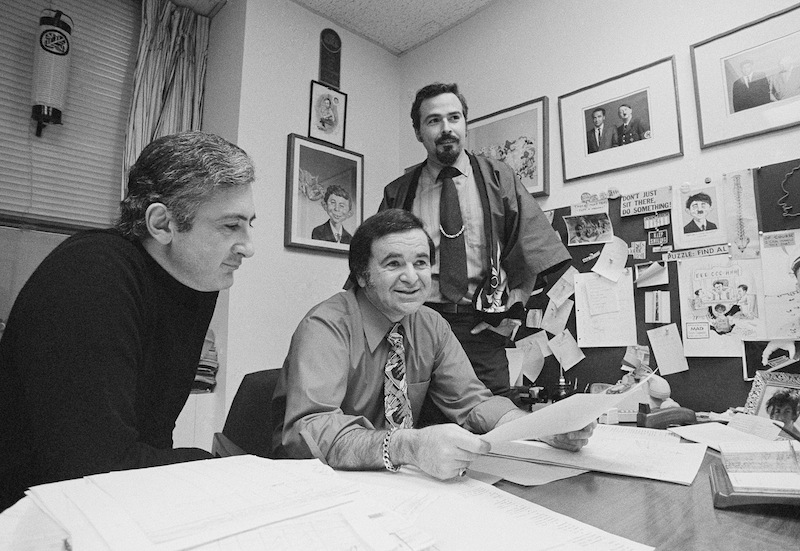

Feldstein and Gaines assembled a team of artists and writers, including Dave Berg, Don Martin and Frank Jacobs, who turned out such enduring features as “Spy vs. Spy” and “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions.”

“The skeptical generation of kids it shaped in the 1950s is the same generation that, in the 1960s, opposed a war and didn’t feel bad when the United States lost for the first time and in the 1970s helped turn out an Administration and didn’t feel bad about that either,” Tony Hiss and Jeff Lewis wrote of Mad in The New York Times in 1977.

“It was magical, objective proof to kids that they weren’t alone, that … there were people who knew that there was something wrong, phony and funny about a world of bomb shelters, brinkmanship and toothpaste smiles. Mad’s consciousness of itself, as trash, as comic book, as enemy of parents and teachers, even as money-making enterprise, thrilled kids. In 1955, such consciousness was possibly nowhere else to be found.”

Under Gaines and Feldstein, Mad’s sales flourished, topping 2 million in the early 1970s and not even bothering with paid advertisements until well after Feldstein had left. The magazine branched out into books, movies (the flop “Up the Academy”) and a board game, a parody of Monopoly.

But not everyone was amused.

During the Vietnam War, Mad once held a spoof contest inviting readers to submit their names to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover for an “Official Draft Dodger Card.” Feldstein said two bureau agents soon showed up at the magazine’s offices to demand an apology for “sullying” Hoover’s reputation.

The magazine also attracted critics in Congress who questioned its morality, and a $25 million lawsuit in the early 1960s from music publishers who objected to the magazine’s parodies of Irviing Berlin’s “Always” and other songs, a long legal process that was resolved in Mad’s favor.

“We doubt that even so eminent a composer as plaintiff Irving Berlin should be permitted to claim a property interest in iambic pentameter,” Judge Irving Kaufman wrote at the time.

By Feldstein’s retirement in 1984, Mad had succeeded so well in influencing the culture that it no longer shocked or surprised: Circulation had dropped to less than a third of its peak, although the magazine continues to be published in local editions around the world.

Feldstein moved West from the magazine’s New York headquarters, first to Wyoming and later Montana. From a horse and llama ranch north of Yellowstone National Park, he ran a guest house and pursued his “first love” – painting wildlife, nature scenes and fantasy art and entering local art contests. In 2003, he was elected into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame, named for the celebrated cartoonist.

Born in 1925, Feldstein grew up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. He was a gifted cartoonist who was winning prizes in grade school and, as a teenager, at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. He got his first job in comics around the same time, working at a shop run by Eisner and Jerry Iger. One of his earliest projects was drawing background foliage for “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle,” which starred a female version of Tarzan.

Feldstein served in the military at the end of World War II, painting murals and drawing cartoons for Army newspapers. After his discharge, he freelanced for various comics before landing at Entertainment Comics, whose titles included Tales From the Crypt, Weird Science and Mad. Much of Entertainment Comics was shut down in the 1950s in part because of government pressure, but Mad soon caught on as a stand-alone magazine, willing to take on both sides of the generation gap.

“We even used to rake the hippies over the coals,” Feldstein would recall. “They were protesting the Vietnam War, but we took aspects of their culture and had fun with it. Mad was wide open.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.