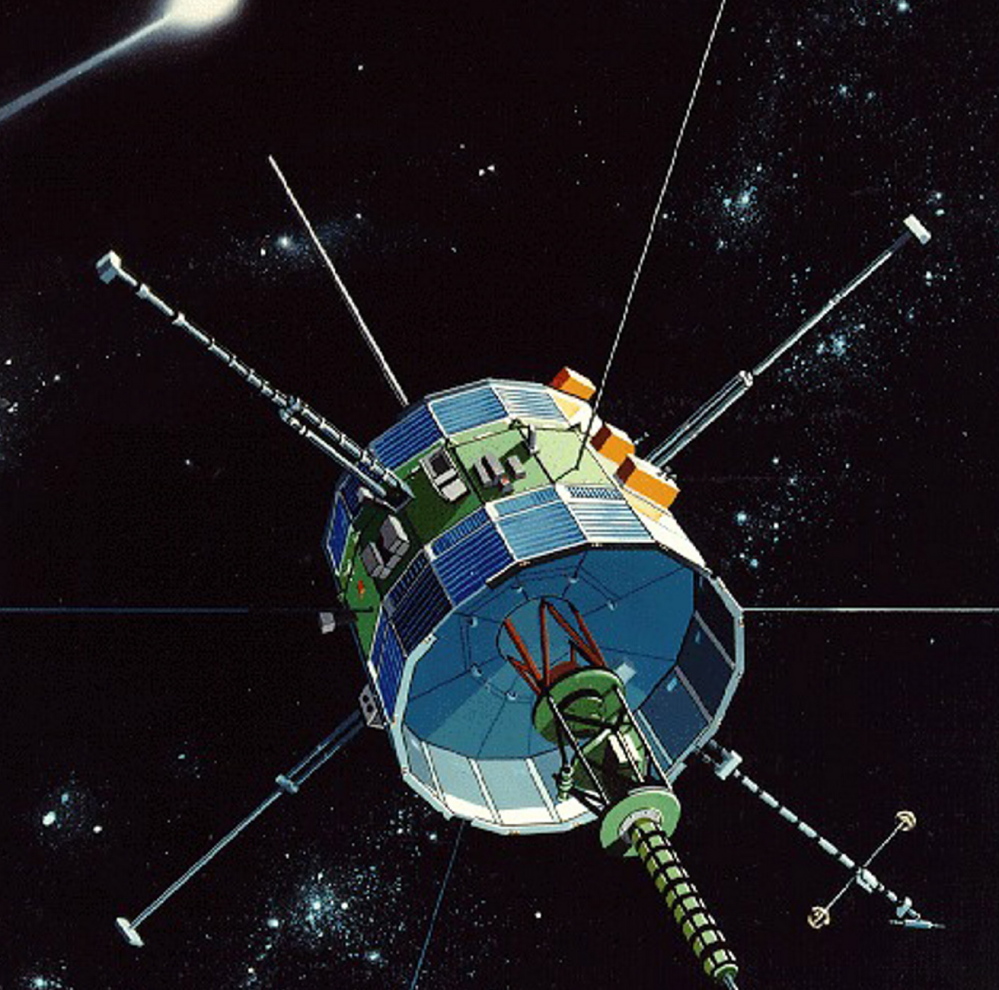

WASHINGTON — When NASA launched a space-weather probe called ISEE-3 in 1978, Jimmy Carter was president, the Commodores’ “Three Times a Lady” topped the charts and sci-fi fans had seen only one “Star Wars” movie: the original.

Thirty-six years and five “Star Wars” movies later, the NASA craft, unused by the agency since 1997, is again the talk of the space world.

A group of garage engineers – ranging from a 23-year-old former University of Central Florida student to an 81-year-old ex-NASA official – wants to get the bookshelf-sized probe working again when it whips by the moon this summer.

The aim is to restart its mission of monitoring space weather and even send it to study an incoming comet in 2018.

“This is something that has never been done before,” said Robert Farquhar, a former NASA manager.

But waking a NASA probe in space for nearly four decades is no easy task. Not only do team members have to figure out how to command the aircraft, but they’ll also have to do it without NASA funding.

Dwayne Brown, a NASA spokesman, said that “re-contacting ISEE-3 would have little scientific value” for NASA.

Still, supporters argue that any new data could be helpful and that reviving the craft could help get the public excited about space. That’s why the team is trying to crowd-fund the project – having so far raised 60 percent of the goal of $125,000.

The “vast majority of the donations are $10 or $50, (but) pocket change in large numbers can turn into something,” said Keith Cowing, editor of the NASAWatch website.

But unless the team can get the probe working again by mid-June – and alter its current flight path – the spacecraft will sail by the moon in August and disappear into space.

“It’s do or die,” said Dennis Wingo, another project director. “Every day is precious. Every hour is precious right now.”

It’s a strange new chapter for a spacecraft last seen on Earth on Aug. 12, 1978.

NASA wanted to better understand solar wind and how it interacted with Earth’s magnetic field, so ISEE-3 was dispatched to a stable orbit 930,000 miles from Earth. ISEE-3 gathered data “at the rate of once every 40 minutes,” according to NASA – 10,000 times slower than current spacecraft.

A few years into that initial mission, however, NASA officials, including Farquhar, commandeered the craft for an entirely different mission: chasing comets. So in the early 1980s, NASA fired the spacecraft’s thrusters and sent it to follow a comet known as Giacobini-Zinner.

The hunt was successful, and in 1985 the craft made history by getting as close as 5,000 miles from the core of Giacobini-Zinner. There it confirmed scientists’ suspicions that comets essentially were space’s “dirty snowballs”: fast objects made of ice, rock and gases.

A year later, ISEE-3 did a similar flyby of Halley’s Comet and afterward spent several years studying the sun until NASA stopped operating it in 1997.

A 2008 test found ISEE-3 was still sending out signals. Still, the team says there’s a major difference between “hearing” signals from the spacecraft and transmitting commands that would allow the probe to fire its thrusters and change course.

So Cowing, Wingo and volunteers have been scouring old NASA documents to gain a better understanding of how the spacecraft works.

Jacob Gold is part of the effort. The former UCF student said he has been developing a virtual model of ISEE-3. He’s also helping to rebuild the craft’s “mission control” center.

“It’s by no means guaranteed,” said Gold, who is now studying aerospace engineering at the University of Arizona. “But we have a lot of good people on the project, and we are getting tremendous support from the Internet community.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.