Starting this fall, Maine high school students will have to do more than show up for classes and eke out passing grades to get their diplomas.

The class of 2018 and those that follow will have to show in-depth understanding, under state-mandated learning standards, of everything from U.S. history to algebraic equations.

Maine is one of the first states to switch to such proficiency-based diplomas, and experts say school districts will have to commit significant time and resources to make sure the system succeeds.

“It’s a very hard thing. People underestimate the amount of time it takes,” said Cari Medd, the principal at Poland Regional High School, which has been held up as a top Maine school for its early adoption of standards-based education and cited as a model for moving from traditional classrooms to a system that requires deep understanding of material.

Under a state law passed in 2012, students must demonstrate proficiency in eight areas outlined in the academic standards known as Maine Learning Results: English, math, science and technology, social studies, health and physical education, visual and performing arts, world languages, and career and education development.

Each school district must decide what it considers “proficient” and adopt new diploma requirements that include the state standards. That likely will produce a patchwork of varying definitions and requirements across the state.

One school that already has a proficiency-based diploma, Searsport High, requires students to get a 3.0 – a traditional “B” – on each standard to graduate. Another district might consider students with “C” grades on the standards proficient.

Districts can add their own requirements to the state requirements, and some already have. In Portland, Casco Bay High School requires every student to do a project that displays in-depth research ability, and to apply for post-secondary education or training.

Portland school officials are considering adopting those requirements at the city’s other two high schools, Deering and Portland. Some parents have questioned that change.

Tim Rozan, who has two children at Ocean Avenue Elementary School, said he applauds the idea of requiring a research project, but thinks it’s overly ambitious to make it a graduation requirement. He suggested instead that a student who does a project could earn a diploma “with honors or with distinction.”

The second of two public hearings on Portland’s proposed graduation policy will be held at 6 p.m. Tuesday in Room 250 of Casco Bay High School.

OTHER STATES MAKING THE CHANGE

State education officials describe the graduation requirements as “one of the few points of leverage available to the state.”

“The passage of this law – and the granting of transition funds from the Maine (Department of Education) to all of the districts – provided the mandate to move towards a proficiency-based system,” says a description on the department’s website. “For districts whose leadership wanted to move in that direction already, it provided cover from resistant faculty or community members. Participants agreed that the passage of the legislation helped to frame the current moment as being appropriate for change.”

Officials with the Department of Education did not return calls for comment.

New Hampshire is the only state that already has gone completely to proficiency-based diplomas. Colorado and Vermont recently passed legislation similar to Maine’s. Dozens of states offer proficiency-based or competency-based diplomas as an option, but do not require them, according to a review of states’ policies by the California-based Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

In Maine, it is likely to remain a political issue, particularly with school districts saying they need more time or money to make the changes. The state has already announced that it will let districts apply for extensions for as much as two years.

In districts that make the change this year, ninth-graders who arrive in the fall will be the first students who will have to meet the requirements to graduate.

EDUCATORS SAY RESOURCES LACKING

The head of the state’s teachers union said many districts are still figuring out where to start.

“We have heard that many schools don’t really know where to start because there has been minimal support to school districts,” said Lois Kilby-Chesley, who acknowledged that the state has websites with information and resource lists but said teachers don’t have time to wade through them.

“Honestly, none of this amounts to a hill of beans when a teacher doesn’t have the time in the day to do their own research into the implementation of proficiency-based diplomas,” she said.

Several educators agree that the standards far above the current rules – in language, for example, or the arts – could be almost impossible to meet, because districts would have to hire many more teachers.

“To become proficient in a language could take years,” said Jeanne Crocker, with the Maine Principals’ Association. “Maine will never have enough language teachers statewide.”

Some schools don’t offer extensive language courses.

“(The standard) has always been there,” Crocker said. “But we’ve never been held to people being proficient. We’ve always said we offer it. Almost no high school requires it. It’s an elective.”

Sen. Rebecca Millett, D-Cape Elizabeth, Senate chair of the Legislature’s Education Committee, said she expects the issue will come up in the next legislative session.

“We certainly have heard mixed reports back from districts as to how they’re doing. Some are really moving ahead at a pretty good pace, and some have done almost nothing,” Millett said. “It’s a pretty short time frame for something that’s this significant of a change.”

LOTS OF EXTRA HELP FOR STUDENTS

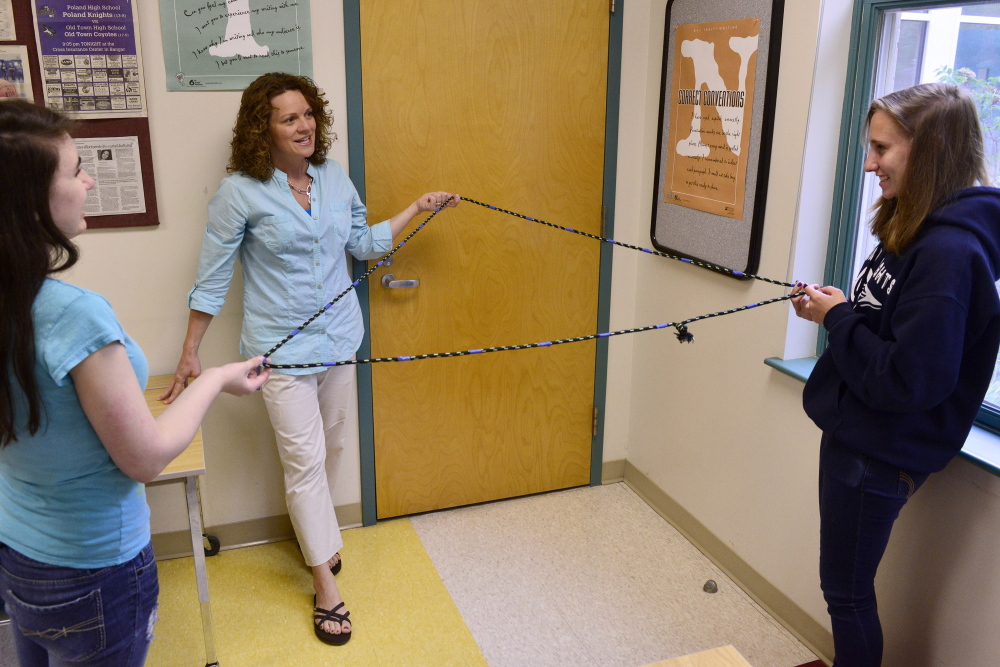

Poland Regional High School, where the education system has been based on the standards for 13 years, has support systems to help struggling students, including a drop-in learning center, four weeks of summer instruction available to any student in any subject area, and an after-school tutoring program three days a week. The drop-in center serves about 30 students every day, and about 100 students attend the summer school.

“We have more of a focus on response intervention as soon as they show they’re below,” said Superintendent Tina Meserve. Most of the support systems are funded in the school budget, she said, and teachers volunteer a lot of their own time, for programs like a once-a-month “catch-up Saturday” program.

“We definitely have staff who go above and beyond,” Meserve said.

Emma Gaul, who is finishing ninth grade at Poland Regional High, said the drop-in center has been a huge help.

“I come down here all the time,” said Gaul, who was at the center on a recent weekday for help with math. “It’s probably one of my favorite things at the school.”

Despite being held up as a model for implementing the new graduation standards, Poland Regional High got a “C” on its most recent report card from the state, down from the “B” it received a year ago. Many schools have questioned their grades since the state started giving them last year.

Poland Regional High’s graduation rate of 84.7 percent is higher than the state average of 83.3 percent. Supporters say it means a lot to earn a diploma from a school that requires students to have a deep understanding of material.

“I don’t view this work as a reform. I view it as an evolution of the very best practices that some schools have developed,” said Mark Kostin, associate director of the Great Schools Partnership, a Portland-based nonprofit. “When we’re clearer about what students need to know and do, we know students are going to be successful.”

Kostin said that schools’ current grading systems may cover up the fact that the student knows some material but may have failed other parts of the subject. In standards-based education, course work is broken down into pieces and all of the material must be understood completely.

“The emphasis is on assurances that you have learned these standards,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.