When you go to the Richard Estes show at the Portland Museum of Art, take a moment to visit Mark Wethli’s 1988 painting “Crossing” on the third floor. Estes is one of the most important American painters, but he has so successfully transformed how we understand realism in painting that his work no longer looks radical to us. “Photorealism” – painting that acts like photography instead of human vision – is our new “normal.”

The Estes show will be revisited in depth in this column, but there is no better comparison with Estes than Wethli, and there is no better time to discuss Wethli’s painting than in a review of his first major show in Maine since 2009.

“Crossing” is a highly detailed view through a spare and clean-lined room fitted with dark wood furniture so simple and sturdy that it will lead most people to see this as a hotel room. If you know Wethli is a Bowdoin professor, you will likely project that setting onto the scene.

Along with a wisp of a lipped jar in profile, there are two simple and otherwise unarticulated forms on the two tables, maybe a book and a box of cigarettes. But it hardly matters – the painting is not interested in the objects or the furniture or the space. It is about the light: reflections, tonal modulations, direct light coming through a door on the right, indirect light flowing in from the tall, slender window directly in front of the viewer, and even the differences between areas of indirect light that is reflected and reflected again. Compare, for example, the light softened through window glass compared to the section below it coming directly through the open window.

The subtleties pile onto each other to create masterful phrases, like where light reflected off a chair leg is framed by the silhouette of the table leg just behind it. It’s like Vermeer to the nth power.

Where Wethli shares a concern with Estes is not within the virtuoso handling of light, however, but within their extraordinary solutions to the extremely complex geometrical structures underlying their compositions.

Whereas Estes’ paintings are immersed in the visual language of photography, “Crossing” is all about the subtleties of human vision. Looking at a photograph, after all, is very different than looking directly at the room around you.

If you only know Wethli’s work from his current exhibition at ICON, then you might think I am writing about a different artist. Your Mark Wethli, after all, paints minimal geometrical abstractions. It can’t be the same guy.

Oh, but it is.

Around 1999, Wethli shifted his primary interest to the underlying structures of his geometrically complex interiors and decided to leave behind the illusionism. From the energy and impact of his abstract work, it was clear from the start that shedding the painstaking technical vocabulary suited him. Wethli was a great painter, and with his move to abstraction, he became even better.

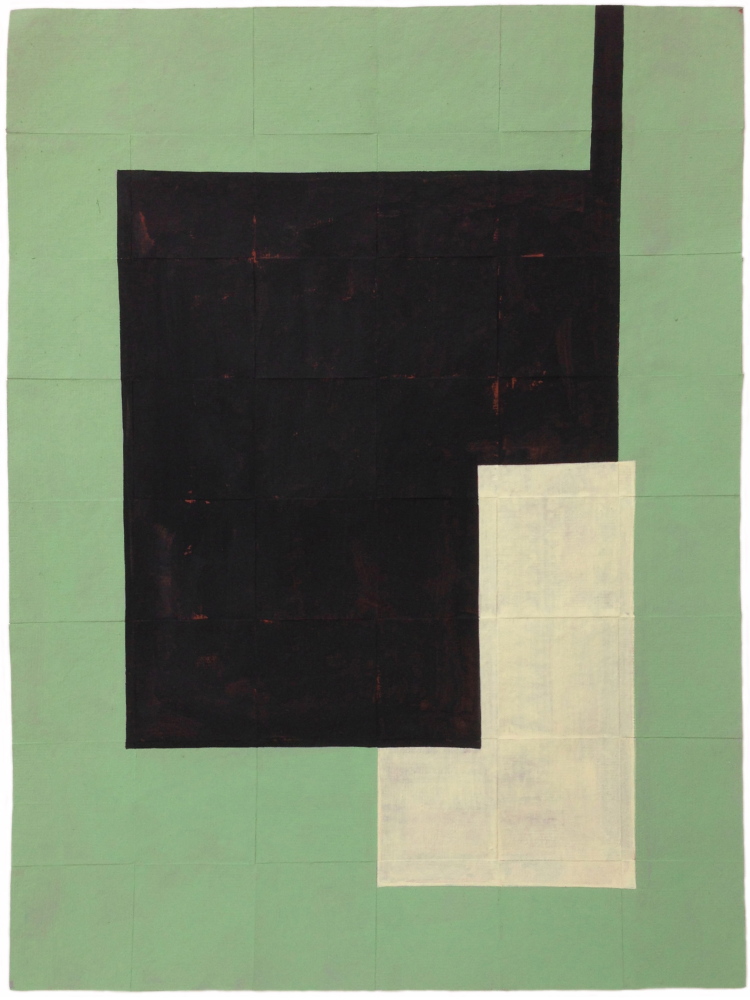

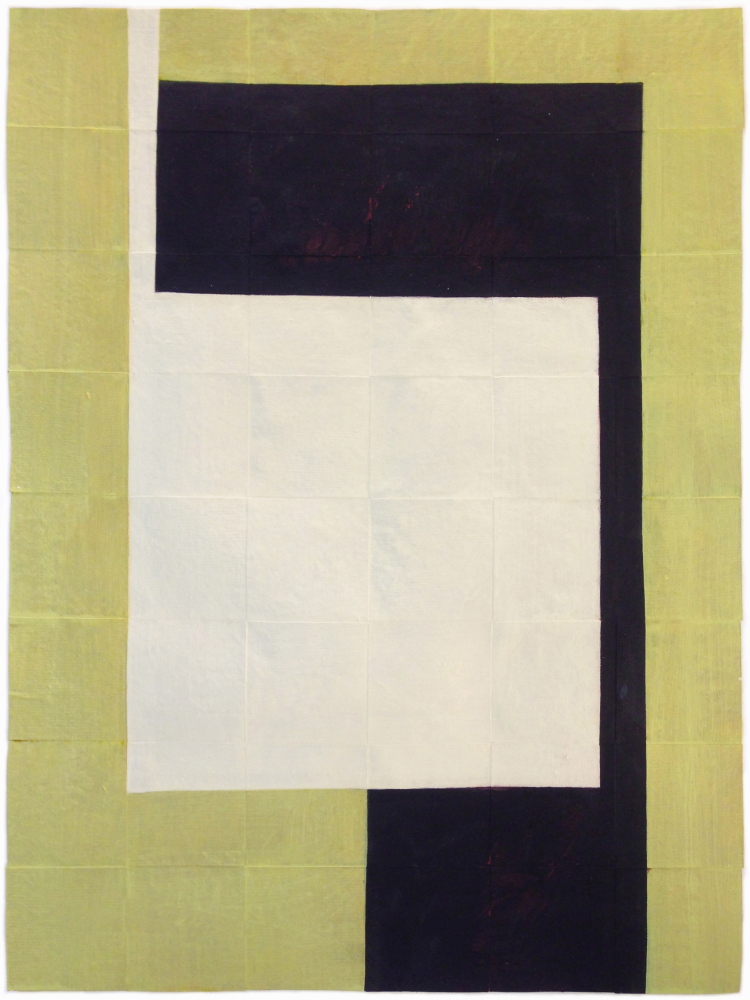

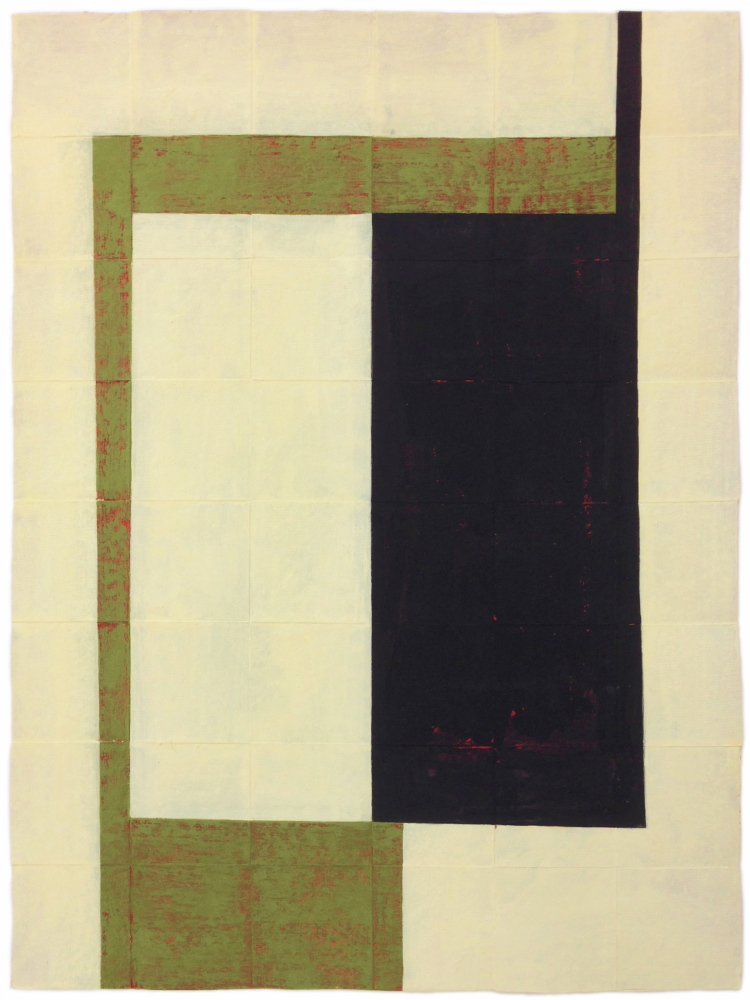

Wethli’s works in “Paintings” are 16-by-12-inch vertical works on woven jaipur paper that use black, a creamy white and a third color (usually a variant of copper green) to present a central pair of rectangle-based shapes that interact with each other, a background color and sometimes a framing shape (to distinguish the white rectangle from the same color background). They are painted in a vinyl emulsion (Flashe) notable for its even, matte consistency. The woven paper is floated on solid white backing under glass in light wood frames.

Wethli’s 2014 “Branch,” for example, features a centered and virtually matched pair of abutting vertical rectangles – one black and the other creamy white. The white rectangle sits on the left. It is demarcated from the white background by an olive green form that rises architectonically from the bottom edge of the paper to just above the adjacent rectangles. The green reaches across the top of the pair until it is cut off by a narrow black segment extending along the right side of the black form straight up to the top of the paper.

This may sound like simple geometric design, but I assure you it is not. The paper is slightly irregular and the forms are not measured or taped, unlike the hard-edged forms of Douglas Witmer, the other painter in this fascinating two-person show. It quickly becomes clear that these works are the product of Wethli’s free-hand abilities and, more importantly, his extraordinary sensibilities.

The shapes are made by pushing the paints up against each other. We see enough pentimenti (painted-over shapes) to know that Wethli has been thinking his way through the compositions – and that his choices matter. Edges aren’t necessarily parallel and Wethli employs this in his vision. Lines that converge or tilt away from each other are part of the breathtakingly subtle punctuation that guides the structures of these paintings.

While his welcome mat might read “push-pull” – that in-and-out logic of American painting championed by Hans Hofmann – Wethli uses such visual assertions to lead your eye throughout the complex formal maps he creates. He also uses these mechanisms to reach towards similar motions sometimes found in Tantric art, an effect that becomes even more pronounced when you let the long, looping pulses of the work deliver what seems to be their intended, meditative effect.

As a painter, Wethli has always had virtuoso capacities for observation. It is what drove his “realistic” interiors and it is the force behind his abstract work. The difference is that Wethli has now positioned himself alongside the viewer. Instead of observing a room somewhere else at a moment in the past, Wethli has brought his process and content together. His immense observational powers are now completely focused on exactly what the viewer sees: the painting.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. Contact him at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.