Maine painting has long been in love with the brush. Skill, swishy swagger and bravado have been here since Winslow Homer put Maine at the head of America’s art world.

But bristle-driven theatricality is only one bit part of the work of the brush in painting. The stroke is the physical connection between the artist and his picture. It is used to layer, set rhythms, blend colors and build up surfaces – or even wash them away. A long, quick stroke can speed your eye along and a grinding mark can slow it to a lingering halt. Brush strokes can play up the literal materiality of paint or hide it behind illusion.

Particularly in modernist art, the brush can be used to draw.

I admit to being seduced by the power of the brush. My favorite painting in the National Gallery, for example, is “Young Girl Reading” by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. To understand why, just look at the mach-speed brushwork – starting with her single-stroke pinky.

It’s why my favorite painters include Anthony van Dyck and John Singer Sargent. And it’s also why – or maybe because – I am a fan of Maine painting.

I have long thought George Lloyd was one of the most talented painters in Maine. But “Paintings and Drawings – A Survey” makes an even bigger case for Lloyd. His work could stand up to anyone, even Matisse and Picasso.

In fact, Lloyd comes across as better with a brush than Picasso. That’s not to say he’s a better artist, more inventive or more important, but it’s not hyperbole.

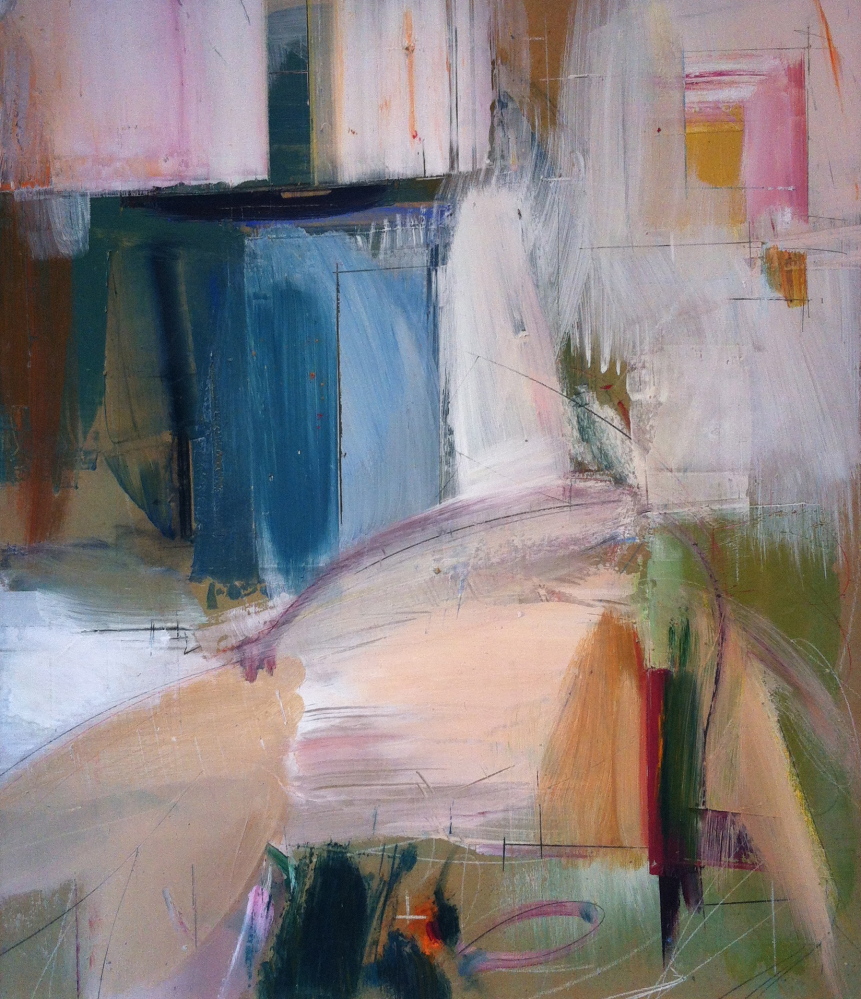

Lloyd’s paintings make the case for themselves from the moment you walk in the door. The centerpiece of the gallery is Lloyd’s 1973 “Composition with Seated Figure.” With the calm clarity of a faceless Matisse, a female figure sits cross-legged facing the viewer. The style combines the simplified drawing of Picasso with the wet, sheer strokes of the Bay Area Figurative Movement, a group that featured artists with whom Lloyd worked and exhibited for many years.

Surrounding the figure in comfortable patches, the colors – led by pinks, greens and browns – weave a rich but subtle compositional solution that lets the figure take center stage. It is on the figure where Lloyd lets his brush sing. The head looks to have been fixed in place with a perfect oval stroke. But the dripping mark reveals the vast quantities of paint being pushed around the surface by the brush.

This element of drawing with the brush within the painted surface is what not only ties Lloyd to the geometrically-nuanced but thick and chewy surfaces of Bay Area giant Richard Diebenkorn, but even to Van Gogh. (Lloyd’s “My Bed” is a telling tip of the hat to Van Gogh’s “Bedroom in Arles.”) And it is not only that Lloyd can draw with the brush, but how he uses it that makes this a great painting: the way a line of the left thigh swoops to make a knee, the infinitesimal curves of the opposing line that moves down the center of the entire leg, a white line reaching up on the right that echoes the figure and weaves it into the compositional fabric, a wide wet stroke tilting down from the head to set the slope of the right shoulder, and then the near-perfect freehand open rectangle hinting at a painting on the wall behind her.

It is these long, straight and even strokes that set the bar for Lloyd’s mark-making. They are a rare commodity in painting, and I am at a loss to think of a painter who has ever done them better than Lloyd.

Nowhere is Lloyd’s linear virtuosity more apparent than in his 1972 “Still Life with Grey Coffee Pot.” It is a horizontal table set for one with plate, utensils, mug and percolator-style coffee pot. What makes it so unusual is that the zoom of the lines is displayed by their straightness rather than their curves. (Zip a pencil across a piece of paper and the ensuing curve is a one-line explanation of Matisse’s drawings.) By the evenness of their textures and their swish as they change direction, paint paths reveal a great deal that cannot be faked.

This kind of surface detail also cannot be photographed particularly well; but the solution to that is pleasant – you have to see the paintings in person.

Lloyd’s work essentially follows the brainy strand of cubism championed by Maine’s John Marin. While Marin’s fame and popularity were largely erased by triumph of Abstract Expressionism, the issues of weaving representation and compositional structures into each other were kept on the West Coast. This makes Lloyd’s survey something of a Maine Odyssey, particularly insofar as curator Mary Harding chose to primarily feature Lloyd’s Bay Area work – rather than the more recent “divided paintings” that dominated Lloyd’s 2006 show at the Portland Museum of Art.

While it is a solo exhibition by a gallery artist, it is a superbly curated show. Harding mixes in new works, drawings, watercolors and smaller pieces to weave a compelling tapestry of context.

Other notable works include an intellectually effervescent pair of watercolors starring “Composition with Drafting Table”; the starkly original and powerfully punctuated “White Divider”; “Standing Woman,” with its genius draftsmanship (that line down the middle and along her thigh…); the endlessly witty black and white and brilliant table-top showdown “Studio Interior with Drafting and Dining Table”; and the splashy cascades of “Exhausted Figure.”

While thinking about brushy bravado always goes up and down, these days drawing is associated more and more with worthwhile brainy content. This makes American painters like Marin and Arshile Gorky more accessible to us. And it is why we can now see how Lloyd knit together many of the best parts of American painting from both coasts well enough to take them someplace completely new.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. Contact him at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.