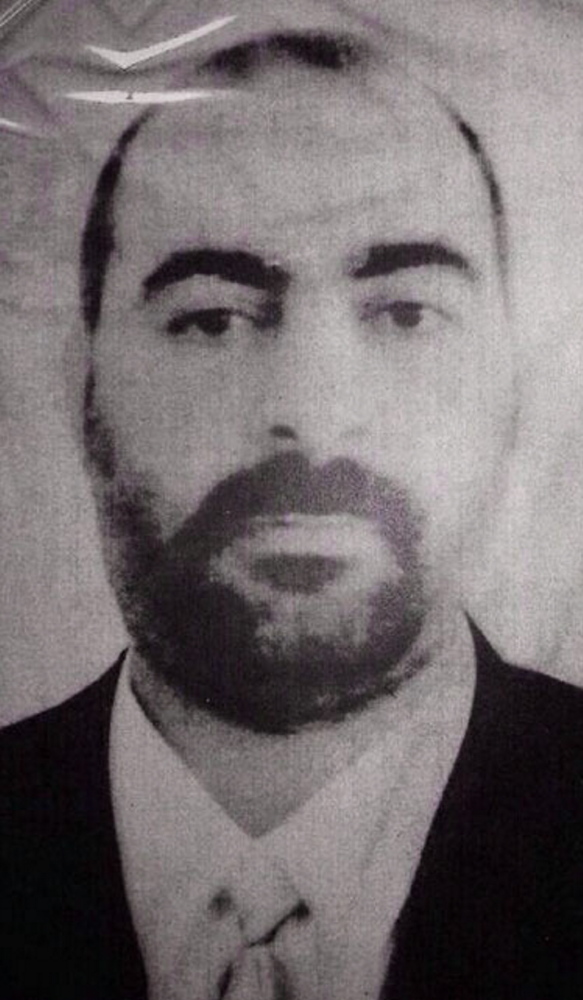

WASHINGTON — When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi assumed command in 2010 of what would become the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, the group already was a largely self-funded, corporation-style organization whose resilience allowed it to grow revenues even as it was targeted by counterterrorism operations.

The militant group al-Baghdadi inherited already had in place a sophisticated bureaucracy with middle managers who were almost obsessive about record-keeping. They detailed, for example, the number of wives and children each fighter had, to gauge compensation rates upon death or capture, and listed expenditures in neat Excel spreadsheets that noted payments to an “assassination platoon” and “Al Mustafa Explosives Company.” Income from the Sunni Muslim militants’ looting of Shiite Muslim-owned property was recorded as “spoils.”

By the time al-Baghdadi took charge, the group even had begun siphoning a share of Iraq’s oil wealth, opening gas stations in the north, smuggling oil and extorting money from industry contractors – enterprises that al-Baghdadi would build on and replicate as he expanded operations across the border into Syria, ultimately breaking from his al-Qaida roots and declaring himself emir of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

DAUNTING ADVERSARY

Now al-Baghdadi’s ISIS has seized control of much of Iraq’s Sunni provinces, is consolidating its hold on two provinces in eastern Syria and is circling the Iraqi capital, Baghdad, as 300 newly dispatched American military advisers arrive in Iraq to assess what the United States can do to stop its advance.

Insurgent records suggest that the United States will find it difficult to rout an organization whose structure and attention to detail allowed it to prosper even during the toughest U.S. counterterrorism efforts of the last decade.

U.S. officials believed, wrongly, the group had been vanquished.

This rare, in-depth look into the seed money and organizational structure of the militant organization comes from the Department of Defense’s classified Harmony Database, a repository of more than a million documents gathered from Iraq, Afghanistan and other war zones. Some 200 Iraq-related documents – personal letters, expense reports, membership rosters – were declassified in the past year through West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center for the use of RAND Corp. researchers looking into the evolution of al-Qaida in Iraq and the Islamic State of Iraq, the precursors to ISIS. Some analysis of the documents, which haven’t yet been published, was discussed with McClatchy to lend context to the current crisis.

The documents provide a cautionary tale as the Iraqi government pleads for U.S. military assistance to beat back ISIS’ brazen new campaign.

The records reveal that previous incarnations of ISIS have had an extraordinary ability to regroup even after military defeats.

That’s the direct result of ISIS’ aggressive and diverse fundraising arm, said Patrick B. Johnston, a RAND Corp. expert on militant financing who’s analyzing the declassified documents.

Johnston said the lessons from the internal records were even timelier now that ISIS reportedly had made off with more than $420 million from banks in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, which fell to ISIS’ control earlier this month. And that’s only part of the valuable assets the militants seized during their virtually unimpeded march across northern Iraq.

THE ABILITY TO RECONSTITUTE

“They continued to raise more and more money over time, even amid the U.S. troop surge and the Sunni Awakening revolt of Iraqi Sunni tribes against the Islamic State, and that’s going to make it difficult for a limited intervention to do more than disrupt ISIS’ pursuit of its objective, which is war to control Sunni areas in Iraq and Syria to establish an Islamic state,” Johnston said. “If the past is prologue, intervention is likely to degrade ISIS militarily, but the funding is the prerequisite to being able to reconstitute itself as it did after the U.S. withdrew its troops from Iraq.”

The documents also challenge popular narratives about the group, including that Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf countries were key contributors to the birth of ISIS – a claim that Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki recently repeated. In fact, the intercepted documents show, outside donations amounted to only a tiny fraction – no more than 5 percent – of the group’s operating budgets from 2005 until 2010, when al-Baghdadi took over after the deaths of two superiors.

Another widely held belief that’s refuted by the financial records is that Iraqi recruits flocked to the Islamic State for higher wages and steady jobs because they couldn’t make ends meet in Iraq’s war-ravaged economy. In the years for which financial records are available, the average Islamic State foot soldier earned a base salary of just $41 a month, far lower than blue-collar Iraq jobs such as a bricklayer making $150 a month.

The low pay is even more striking against the background of the risk these new members incurred. In Anbar in 2005 and 2006, Islamic State fighters were 47 times more likely to die than the general population of men ages 18 to 48, according to the RAND analysis. The conclusions echo what counterterrorism experts have long suspected: that members are so ideologically driven that economic incentives to stop the flow of fighters aren’t likely to have much impact.

Because the documents obtained by RAND end in 2010, there’s still no complete picture of how al-Baghdadi has built on the business model to finance his group’s current involvement in Syria and Iraq.

Estimates of the group’s current war chest go all the way to $2 billion, factoring in new revenue from Syrian natural resources and other battlefield spoils, making ISIS the richest militant group in the world.

Charles Lister, who researches extremist groups as a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Doha Center in Qatar, said there was no evidence that foreign donors such as Gulf nations became any more important to the group after 2010; he dismissed that idea as stemming from a “political context of deep suspicion and paranoia.”

The group has suffered setbacks, Lister said, noting that ISIS was forced to withdraw from Idlib province in northwestern Syria.

Even so, the group still has access to oil resources in northeast Syria and, with its newly won prizes in Iraq, appears comfortable enough to put money concerns aside and focus on the fight.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.