Where on Earth is South Africa? You could probably locate it on a map (thank goodness the country’s name helps out with that), but on wine shop shelves and restaurant menus, a nation that has been producing wine since 1659 exists mainly in dreams.

Or nightmares, the ones that include Pinotage. I know there’s good Pinotage. With anything, there’s some good something somewhere. I don’t mean to be disrespectful. But too often, the wines from this native cross between Pinot Noir and Cinsault strike me as a perverse adolescent dare: Stuff a Band-Aid inside a used gym sock, light it on fire, douse it in sweetened coffee and gulp it down. I’ll give you five dollars.

Is this why the wines of South Africa suffer in our neck of the woods the frequent banishment to low shelves, bargain bins and back pages of wine lists under the heading “Other”?

Well, fine, then. As I pretty consistently argue, often “Other” is where the most interesting wines are to be found, especially if you’re into cost-benefit analysis. With South Africa, you can often find an outlook and set of flavor expressions much closer to traditional French country wines than anywhere else in the Southern Hemisphere.

That’s partly due to colonial history: Dutch East India Company, French Huguenots, etc. It’s also due to soil and climate. The latter, in the wine regions that predominate along the coast, is rather Mediterranean. The former is tremendously varied, created and organized by mountain ranges. And then there are the winemakers themselves, who have looked for the best ways to establish French varietals in their homeland’s unique terroirs.

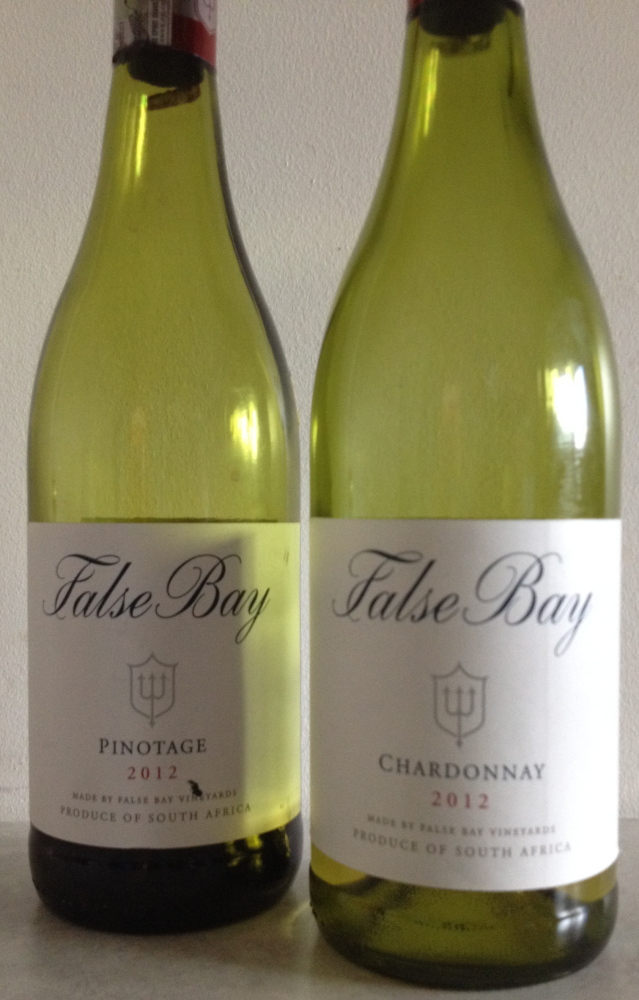

A primer on South African wine is beyond my experience, knowledge and allotted newspaper space. But I’m so happy to have found the wines of the Western Cape’s False Bay Vineyards. False Bay is the second label of Schapenberg’s biodynamic, very-natural stalwarts Waterkloof.

The False Bay wines are made from sourced grapes, rather than the estate-grown fruit at Waterkloof, and while not every natural-wine benchmark is reached by every False Bay wine, the emphasis on clean lines, pure varietal expression and deeply established harmony is consistently evident.

“We’re aiming for elegance, value for the money and typical varietal characteristics,” Nadia Barnard, cellarmaster at Waterkloof and False Bay, told me. “We want balance above all. So we buy from many different regions for each varietal, and the most important thing for me is choosing the right time to pick, with all harvesting done by hand. We’re never going to add acid to a wine, and since we’re working with wild ferments, we have to get it right in the vineyards.”

All the wines undergo relatively leisurely fermentations: at least five months, with more than six months of lees contact after that. Allowing time for the wines to self-construct is what is what gives them their remarkable multilayered quality and graceful arcs of flavor.

Barnard is from South Africa and studied enology at Stellenbosch, but she learned much from stints in Australia, Chablis and New Zealand. It shows.

I’m not saying the False Bay Chardonnay 2012 ($13) is like Chablis. It is ripe and fleshy, tangy-tropical, emotionally very open and relaxed, not the least bit held-back. But the wine comes by those traits honestly. The grapes are from the chalky-soiled Robertson area, and the juice doesn’t touch oak, doesn’t undergo malolactic fermentation. Dramatic diurnal temperature fluctuations in the vineyards are responsible for a prickle of refreshing acidity throughout that caused me to triple-check the listed 14 percent alcohol. The wine’s Chablis influence comes across in a salty lick of flint off the back end, just about forcing your lips to smack.

“What I enjoyed in Chablis was the finesse of those wines,” Barnard told me. “Chardonnay is not the most aromatic varietal, but it’s so expressive of terroir. We don’t have that distinctly intense minerality of Chablis here, but we can bring out the grape itself if we’re humble about it.”

From oak-chip-soaked vanilla boats to stainless-fermented enamel-rippers, there’s an intimidating haystack of cocktail-yeasted inexpensive Chardonnays out there, and precious few needles. False Bay’s is a needle.

The Chenin Blanc 2012 ($13) is at least as enticing, though perhaps less needle-like just because there’s so much less bad Chenin in the world than there is bad Chardonnay. An entire percentage point lower in alcohol, yet fuller on the tongue, as is this intriguing varietal’s nature, the Chenin Blanc tones down the fruit characteristics, aiming instead for gardens and trees: the bittersweet pull of anise hyssop, the white-flower tickle of Solomon’s Seal, the dry stretching-out of almonds and beeswax.

Chenin thrives in relatively dense soils and warmer climates. False Bay sources its Chenin from bush vines, some of them more than 70 years old, from vineyards in the rightly famous-for-Chenin Swartland area. If this wine doesn’t make you want to get a “Chenin” tattoo on your left bicep, I won’t be of much use to you in the future.

And then, there’s the Pinotage. This story wouldn’t be complete without mention of it, and I’m enough of a classicist at heart that I’m not going to tell you a story without a happy ending. Pinotage was developed at Stellenbosch, a cross of Burgundy’s delicate Pinot Noir and southern Rhône’s high-yielding Cinsault. As Barnard explained it to me, “For Pinotage, in terms of picking and fermentation, you can lean toward the Cinsault or the Pinot Noir. We tend toward the Pinot side.”

That means it’s not picked too ripe, nor is it left on its skins so long after crushing as to result in overextraction and those infamous burned flavors. Relatively short time on the vine, in the tank and aging in barrel all yield a rare bird indeed, a Pinotage without too many points to prove.

Not quite as gauzy and glassine as Pinot, yet certainly influenced by that varietal’s inimitable precision and buoyancy, the False Bay Pinotage 2012 ($13) is excellent. It’s a cool-tempered wine, closest to a balanced Sonoma Cabernet, wild-herby and granitic, or a young Bourgeuil, with its notes of lilac and pepper and a fourth-gear acidity. For just about any land animal off the grill, herb-crusted and unsauced, this is a Pinotage to come back to again and again.

None of these wines is going to blow you away. That’s not what False Bay is here for (perhaps Waterkloof’s top-tier line of wines would, but those wines are not currently available in Maine). These wines are here to bring a great amount of pleasure, in a loose and affable sort of way, for not a lot of money. False Bay wines, benefiting from what Nadia Barnard calls “a modern approach along the lines of New Zealand and Australia, but based on a distinct centuries-old heritage,” are the best sort of utilitarian beverage: balanced, clear, interesting but not distracting. They might just help move the wines of South Africa onto a shelf of their own.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. Contact him at soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.