At first glance, the notion of “Maine to Greenland” as a geographical entity seems a bit of a stretch. However, in their book of the same title, that is the argument that authors William Fitzhugh and Wilfred Richard set out to make. And using the umbrella of a “Maritime Far Northeast,” they largely succeed. These lands, they write, “have always been porous, interlinked by many waterways, common species of animal life, and shared cultural and linguistic ties.”

The term “Far Northeast” was originally coined by anthropologists seeking to understand the region’s cultural history. To this, the authors have added the maritime aspect that as much as any other feature binds and defines this chunk of the earth. It “extends through forty degrees of latitude,” and ranges in climate from temperate to arctic. To history and culture, they add geography, ecology and geopolitics.

Fitzhugh directs the Arctic Studies Center at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Richard, a well-known photographer in Maine, has spent a lot of time with Fitzhugh and the center as a researcher in various archaeological projects throughout the region. The experiences of these expeditions are the basis for their book. While “Maine to Greenland” has a decidedly academic bent, it also reflects both men’s passion for and 40 years of travel in this often forbidding region.

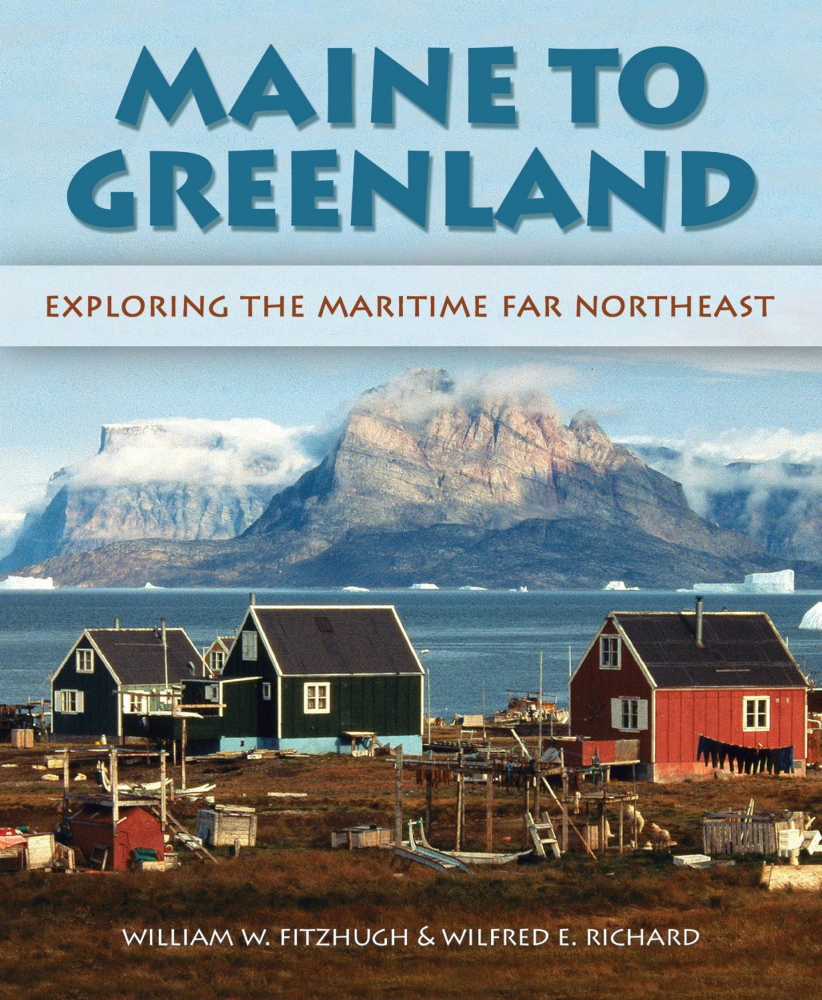

Richard’s magnificent photographs especially make it a handsome addition to the coffee table, a subtitle of which might have been, “Everything you wanted to know about the region, but didn’t know you wanted to know.”

After an overall sketch of the land and its exploration, the authors take the region pretty much by its political divisions, starting with Maine, “the southern Anchor.” Proceeding north, chapters are devoted to the Canadian Maritime Provinces, Quebec’s Lower North Shore, and then on toward the Arctic Circle through Labrador, Nunavut and Greenland.

Each chapter is a small encyclopedia that deals with the area’s culture, history and ecology, but also includes vignettes of the people the authors encountered on their travels. Inevitably, given the very linkages that make up the book’s premise, there is some repetition, and one wonders if certain aspects – the changes in prehistoric cultures, for instance – might not emerge more clearly if treated holistically.

On the other hand, today’s political divisions are themselves the result of history, and the succession of colonists that started with the Norsemen a thousand years ago has made it a rich one. After the Vikings came Basque and Portuguese fishermen followed by the thrust and parry of the French and British empires. Their impact is to be read in the names and customs of the land today.

Not surprisingly, given the rapidity with which it is affecting northern latitudes – the Northwest Passage became ice-free for the first time in recorded history in 2007 – global climate change is a major concern. In a separate chapter, its progress is documented with maps, time lines and personal anecdotes. Among the researchers’ major worries while on expeditions is the increasing number of icebergs, spawned by retreating glaciers, through which their vessel must thread its way.

“We were looking for answers that could be applied to our rapacious consumption of the earth’s most precious resources,” write Richard and Fitzhugh. They find them in the “small-scale societies” that typify the region, which they hope can be “sources of inspiration for new ways of adapting” elsewhere.

Ironically, this land of isolated communities, heretofore only “grazed by whalers, occasionally exploited by miners and fishermen, and coerced into hosting Cold War Distant Early Warning and military installations” is about to be forcibly integrated into the modern world as the race intensifies for oil and minerals below the Arctic Ocean and the Northwest Passage becomes a major shipping lane.

The use of acronyms – the Maritime Far Northeast often becomes the MFNE – seems at odds with the authors’ emphasis on their spiritual feelings for the region. Every now and then, the sheer quantity of information in the text seems to defy their ability to present it logically. And there are a few careless mistakes. As a Scotsman and therefore from the analogous region across the pond, I have to point out that James I of England was James VI of Scotland, not the other way around.

But these are quibbles. The Smithsonian has done its researchers proud with a book that is beautifully produced and designed. Anyone with any interest in the Maritime Far Northeast will find Maine to Greenland as rich a treasure trove as the lands it explores so attentively.

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and the author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.