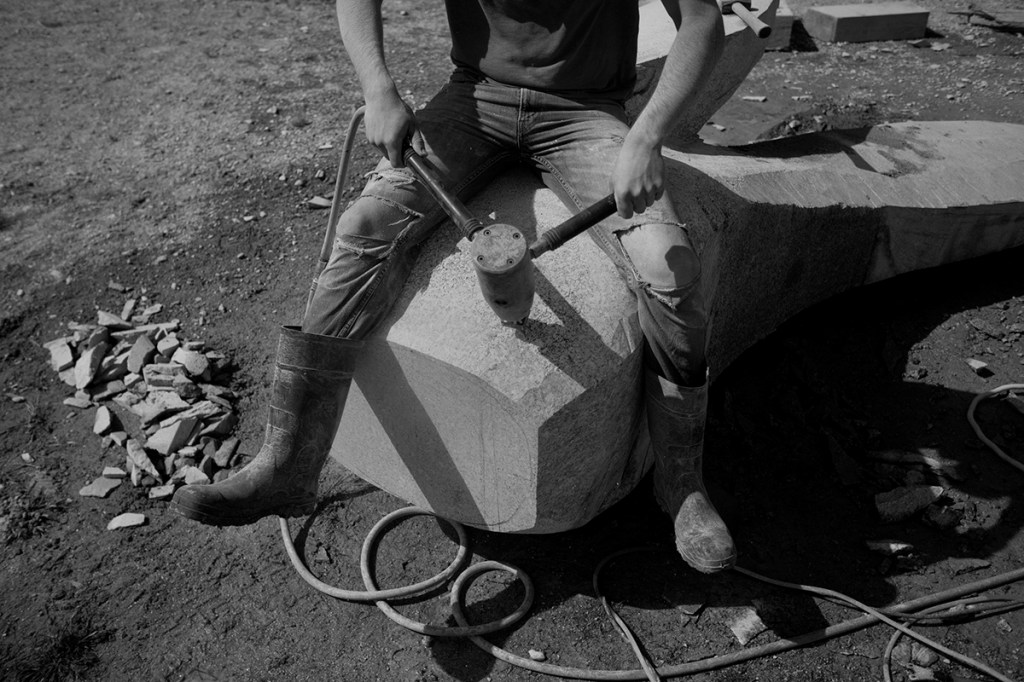

PROSPECT HARBOR — A cloud of white dust forms over a giant block of granite. Hammer in one hand, chisel in the other, Bertha Shortiss launches chunks of rock with each swing of her arm.

Most land in the grass around her, but this is hard-hat territory that more resembles an industrial site than a place we might associate with art-making. There’s a steady hum of generators, the whiny pitch of grinding tools and the tap-tap-tap of hammer and chisel. The diesel engine of heavy machinery rumbles to life, lifting a 5,000-pound block of rock on top of another.

Chalky residue outlines the sculptor’s protective gear, which blends with sweat when Shortiss pulls the goggles and respirator from her face.

“I’m trying to create the feeling of movement and waves,” says Shortiss, a 46-year-old sculptor from Altdorf, Switzerland. “I’m trying to create a lot of movement in my piece.”

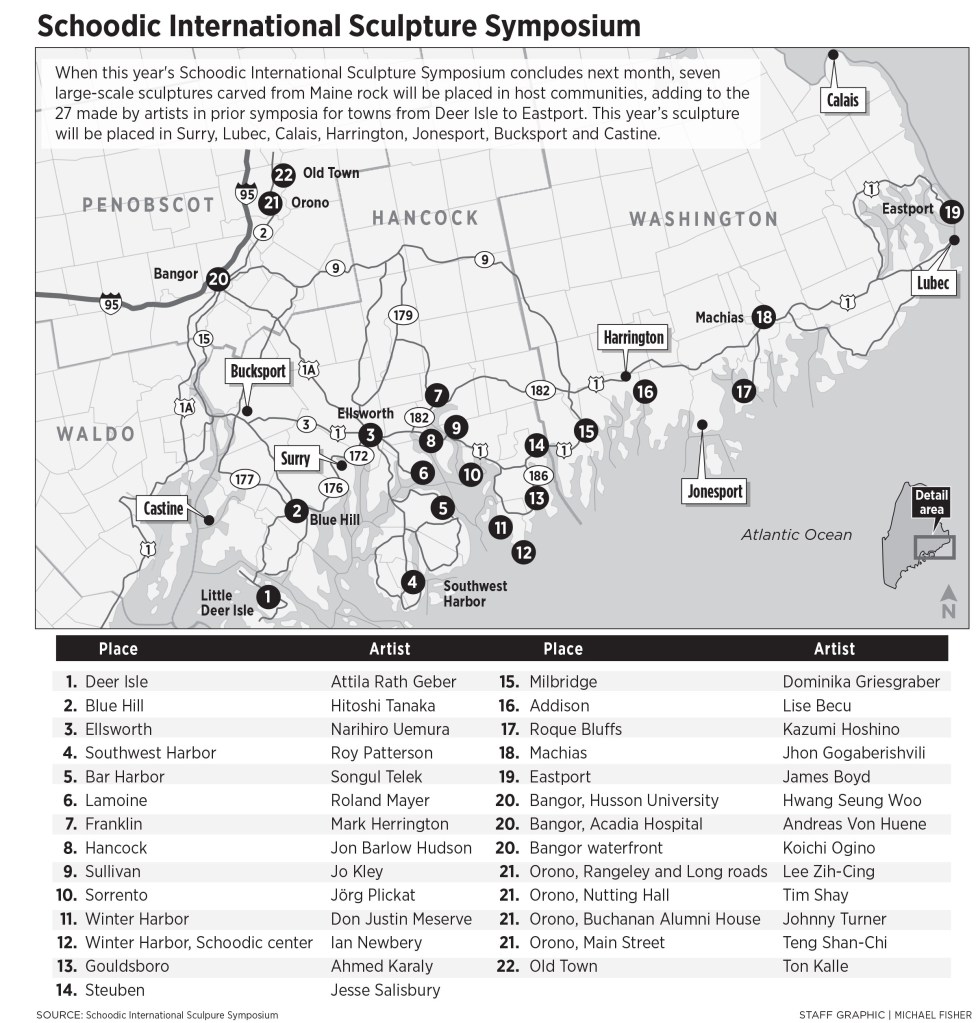

Shortiss is spending her summer in the tiny community of Prospect Harbor in Down East Maine, one of seven sculptors participating in what may be the final installment of the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium. Operating mostly on an every-other-year cycle since 2007, the symposium has resulted in 34 large-scale permanent pieces of public art across a wide swath of eastern Maine, from Deer Isle to Eastport and as far north as Old Town. It is the largest collection of public art in Maine, and represents a $1 million investment by host communities, individuals and foundations.

All the sculptures are made from rock quarried locally, by more than 30 artists from 14 countries. Many of the U.S. artists live and work in Maine.

They come together for six weeks, each working on individual pieces in a group setting. When the symposium closes, the sculptures are placed in communities that raise money to support the project. Twenty-seven have been placed so far; seven more will follow in September in Surry, Lubec, Calais, Harrington, Jonesport, Bucksport and Castine.

The artists work at Fisher Field, a community baseball diamond off Route 186 in Prospect Harbor. Visitors are encouraged to observe them as they chisel or saw away in the open field or under tents to shield them from the sun.

Some days, only a handful of people show up. But when the weather is nice, as many as 200 visitors pass through the grounds from morning to sundown. About 8,000 people will attend this summer.

Closing ceremonies are scheduled for 1 p.m. Sept. 10, when the seven finished pieces will be on view and the artists available to discuss the project.

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

This work is ambitious. Some pieces tower as high as 15 feet off the ground, constructed from a single cut or with multiple pieces of rock shaped and formed by machine and hand. Some lay squat, spreading horizontally across the ground.

There are abstract forms and realistic interpretations of nautical motifs. The rock may be smooth and finely detailed, or remain in its rough, natural state with the mark of quarry drills visible on the sides of granite blocks, indicating where they were lifted from a larger bed of rock.

Once placed, all of the sculptures become focal points of a community, marking rivers and harbors, anchoring public parks or beckoning entrance to a library, school, municipal building or hospital.

“I think this project has changed Maine art history, for sure,” said Jesse Salisbury, the Steuben sculptor who founded and directs the symposium. “We have raised the bar on the level of the public art and community involvement. We’ve been able to convince local people to invest in public art and become art collectors as a society.”

The project taps Maine history.

Granite once dominated Maine’s coastal economy. Ships loaded with Maine rock sailed down the East Coast, supplying building foundations, columns and piers for the Brooklyn Bridge in New York and the Washington Monument in the District of Columbia.

In 1900, Maine had more than 150 quarries that employed 3,500 people. The advent of steel and reinforced concrete made granite less desirable.

Today, only a handful of quarries still harvest granite.

Salisbury, whose work is on view at the Portland International Jetport and in public and private collections in Maine and around the country, conceived the symposium as a way to build a large collection of public art in a part of the state that has little of it, and to use that art to help residents connect with their past.

“Granite is just such a huge part of our state’s history,” he said. “It’s a 100-year-old trade, and this is a way to celebrate that history with art.”

BASED ON A EUROPEAN MODEL

Salisbury organizes the Schoodic symposium around a European model that emerged in the mid-1900s. Sculptors gathered in a central location to make work and learn from each other, while inviting the public to observe. The finished work became part of a public collection in the host community.

Schoodic follows that model nearly exactly, and adds the local history element by using native rock. For this year’s symposium, Salisbury arranged for 70 tons of Maine granite.

He envisioned the Schoodic Symposium as a series of five separate events. This year’s will be the last, although Salisbury is not ruling out another if he can garner support. “This is all we have planned, but we’re not saying it won’t happen again,” he said.

Shortiss is making a swirling, towering piece that loosely resembles a G-clef note. It’s wide on the bottom and narrows at it rises. She designed her piece with the movement of water in mind, and chose a piece of granite that suggested a wave. Her piece will be placed in the town of Surry, near the water.

Shortiss was among 200 artists from 52 countries who applied to participate. She heard about the Schoodic symposium through a German friend. She likes the idea of working among artists in a public place, where visitors are encouraged to observe. She also likes to work big – something that usually doesn’t happen without a private commission.

This is her first trip to Maine.

“This is a great opportunity to make a big sculpture for a public place, which is very nice,” she said. “I don’t get that opportunity very often back home.”

Roy Patterson has the distinction of being the only artist selected for two Schoodic symposia. He was part of the first in 2007, which resulted in a piece at the library in Southwest Harbor. He was asked back this summer as a replacement for a foreign artist who had to cancel just before the symposium began.

Patterson, who lives and works in Gray, is creating what he describes as “the figure as landscape.” With five granite blocks, he is making a reclining figure that appears as granite wall. He was inspired by the way the ocean smooths stones on the Schoodic peninsula.

He thinks the Schoodic project is the most enduring public art project in Maine, in part because of the long-lasting nature of the material.

“It’s a significant collection of monumental works,” he said. “How Jesse was able to talk all these towns into doing it, I still don’t know.”

Salisbury, 42, laughed at the compliment.

“I was too young to know better, and too stubborn to give up,” he said.

Salisbury and his board have a budget of $252,000 for this year’s effort. Just less than half that amount – $118,000 – comes from private donations. Another $30,000 comes from grants, and $84,0000 is raised by the communities where the sculptures end up.

Communities assemble a local committee, which is asked to raise at least $12,000 in return for a sculpture.

Lisa Marin, who teaches art in public schools, heads up the committee in Jonesport. She and her colleagues are within $1,000 of reaching their fund-raising goal.

“Our leap of faith is going to pay off,” Marin said.

COMMUNITY BUILDING

The project has brought people together and focused the community on art, history and culture, she said.

“Anytime you can get people working together for the arts, that’s a good thing,” Marin said. “And that’s especially true in Down East Maine, where we are so far away from museums.”

She has taken students to previous symposia to introduce them to sculpture and teach them the history of quarrying in Maine, as well as the intersection of art and industry. Her science-teaching colleagues also have gotten involved, she said.

The Jonesport piece is a towering sculpture that resembles a twisted rope. Its nautical theme is appropriate for Jonesport, Marin said. It will be placed in a newly created public park that overlooks Moosabec Reach.

South Korean artist Kyoung Uk Min is making the piece. The day he and his wife arrived in Maine, Jonesport hosted them for a lobster bake, took them on a boat ride to a local island with a granite quarry, and put them up in a cottage for the night. The next day, Marin gave them a tour of the local historical society and sardine museum, and then arranged another community lunch.

It was important for the artist to get to know local folks and understand the history of the town before beginning the sculpture, Marin said.

Tourists have begun incorporating Schoodic sculptures into their vacation planning. The symposium publishes a map for self-guided tours, and the province of New Brunswick also promotes a collection of a half-dozen pieces of public art just over the border, in and around Saint John.

New Brunswick is hosting its own symposium, with eight planned pieces. After the seven new sculptures in Maine and eight in Canada are placed, there will be 48 pieces of public art in Maine and nearby in Canada. Collectively, those pieces are known as the International Sculpture Trail and promoted on both sides of the border.

Dee Johnson arrived in Prospect Harbor last week, mostly by chance. She is from West Coast of the United States and was traveling in Maine with a friend. She likes to participate in RV rallies and plans to suggest a rally in Maine next summer organized around a sculpture tour. The Maine part of the trail covers more than 200 miles west to east. There’s plenty to do along the way, she said, and the sculptures offer incentive to explore communities on the coast and inland as far north as Old Town.

“I just think it’s wonderful,” she said. “I wasn’t planning on coming here, but now I plan to come back.”

At midday, the artists break for lunch, which is provided by volunteers from host communities. On this day, it’s chili.

Visitors take advantage of the pause to get closer to the work. Some collect chunks of discarded rock as souvenirs, talking quietly among themselves.

The generators have been silenced. Tools sit idle on blocks of granite, alongside dusty gloves and earplugs. As loud as the ball field was in the morning, it’s mostly quiet now. The only sound is a barking dog on a leash across the field.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.