In December 2012, University of Maine football player Zedric Joseph was arrested on a domestic violence charge for allegedly choking his girlfriend so hard he left marks on her neck.

Under a then-new state law, Joseph could have been charged with aggravated assault, a Class B felony. Instead, he was charged with a misdemeanor simple assault that was eventually pleaded down to disorderly conduct.

Eighteen months later, Joseph was charged with holding a knife to the neck of the same woman and murdering a man he found in her company.

Today, police and prosecutors in Maine are much more likely to charge someone with aggravated assault when a victim is strangled – defined as cutting off the blood flow or breath by applying pressure to the throat.

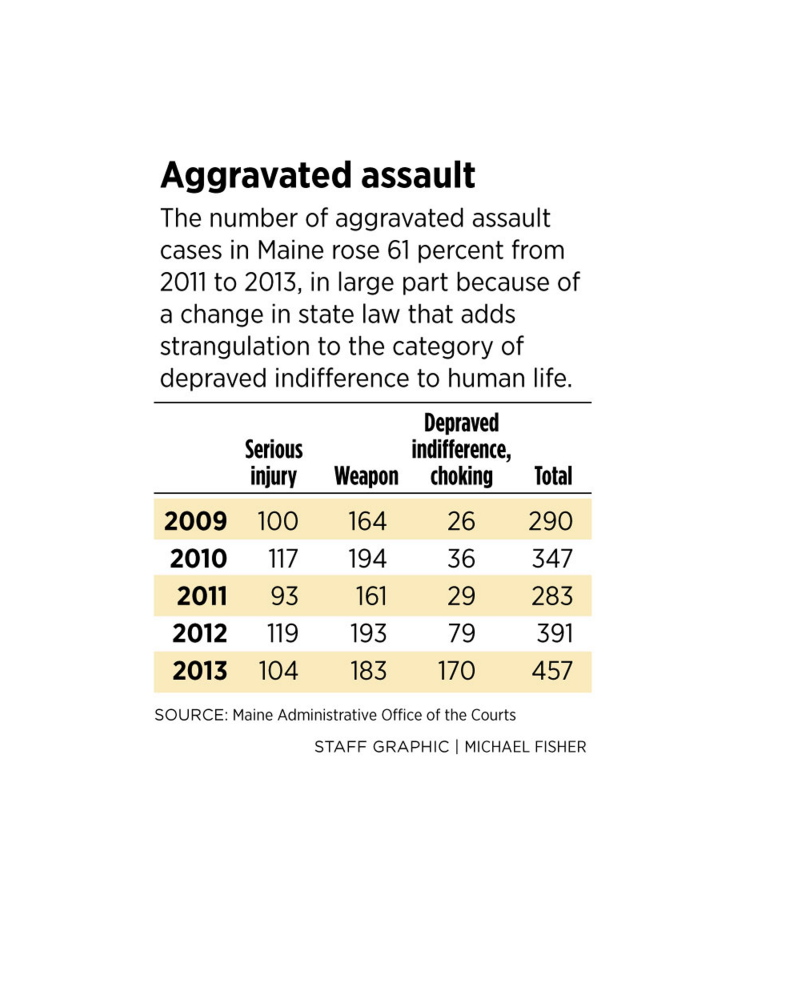

A Portland Press Herald analysis found that the number of aggravated assaults charged by prosecutors rose 61 percent from 2011 to 2013. The number of times prosecutors charged defendants with showing extreme indifference to the value of human life – the section of the law where strangulation was added in 2012 – jumped from 29 in 2011 to 170 in 2013, more than a sixfold increase.

“That is exactly what we were hoping for,” said Julia Colpitts, executive director of the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence. For years, strangulation was not treated as seriously as victim advocates believe it should have been.

“There’s something so intimate and terrifying about having your breath choked off,” she said. “You know you can die. When you’re hit or harmed it hurts, but you don’t have that immediate awareness you’re going to die.

“The immediacy and the dominance is far greater than backhanding someone or punching them. Even when the offender releases the pressure, the point’s been made: You could have been dead.”

Changing the law was a priority for the coalition in part because of research done by the Maine Domestic Violence Homicide Review Panel, which found that in many cases, strangling someone was part of an escalating pattern of violence on the part of the offender that ultimately led to death.

The coalition surveyed victims of domestic violence to gather their input on the severity of choking and presented that information to the Legislature’s Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee. Most of the 151 victims surveyed said they had been strangled on at least one occasion, most of them multiple times.

One victim who had been choked was quoted in the report as saying: “It is the worst. I’d rather be hit all day long.”

There are three types of aggravated assault under Maine law: Using a weapon, causing serious injury, or injuring someone “under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life.”

Whether someone used a weapon or caused serious bodily injury are clear behaviors that make prosecution on the charge relatively straightforward, said Geoffrey Rushlau, district attorney for Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Waldo and Knox counties and vice president of the Maine Prosecutors Association.

“‘Manifesting extreme indifference’ has been around for decades, but most prosecutors and police viewed it as less concrete as the other two ways of charging agg assault,” Rushlau said. “Adding the definition of strangulation, which is so concrete, certainly raises the visibility” of the statute.

John Pelletier chairs the Criminal Law Advisory Commission, which reviews changes in criminal law proposed to the Legislature. He said a judge or jury still must conclude that strangulation in a given case represents indifference to human life.

“I’m quite certain no one in the room thought there would be a 40 percent increase in the number of aggravated assaults charged,” Pelletier said of the panel’s deliberations. “Either members were not aware of how common this is or (didn’t realize) how these prosecutions work in the real world.”

Since 2009, the overall number of domestic violence simple assaults charged by Maine prosecutors has stayed relatively stable, from a low of 3,131 in 2010 to 3,322 in 2013.

The number of aggravated assaults involving weapons or serious injuries ranged from 254 in 2011 to 312 in 2012.

The strangulation language was added to the statute in 2012 and took effect midyear.

Since then, the number of aggravated assaults in which “indifference to human life” was cited jumped from 29 the year before the change took effect to 79 by the end of 2012. By 2013, the number had grown to 170.

Advocates for domestic violence victims have been leading training seminars for police and prosecutors to recognize, investigate and prosecute strangling. They say “strangling” is a more appropriate term than choking, which typicallty refers to having something like food lodged in the throat, blocking breathing.

Strangulation isn’t always obvious to first responders, Colpitts said. Bruises may not show up for a day or two, or even at all. Sometimes one sign is a hoarse voice. Often the victim, besides being scared, is disoriented and their account of events may be incomplete or incoherent.

There are health consequences to being repeatedly strangled as well, because it deprives the brain of blood flow. “It can kill you very quickly and it can cause permanent damage if your throat is constricted for even a short amount of time,” said Lois Galgay Reckitt, executive director of Family Crisis Services, serving domestic violence victims in Cumberland County.

Statistics gathered from Maine police departments for the FBI showed that the only violent crime that increased from 2012 to 2013 in Maine was the number of reported aggravated assaults, which went up 17 percent, from 803 to 943.

That is much higher than the number charged in court. One of the reasons for the disparity is that an officer makes an arrest based on probable cause that the crime was committed, a lower standard than the standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” which a prosecutor needs to secure a conviction, he said. A prosecutor may also conclude that strangulation did not by itself denote indfference to human life, and so it is charged as simple assault in court. Some reported aggravated assaults also remain open investigations.

Not all of the increase in aggravated assaults stems from domestic violence.

Maj. Gary Wright, head of operations for the Maine State Police, said there has also been an overall increase in the level of violence, with more people using knives and other weapons or causing serious injuries.

“One of the things we all are seeing across the board is a lot of confrontations taking place on the street now that used to be somebody punching somebody. Now one of them pulls a knife. Even if it’s superficial, non-life-threatening, it’s still an aggravated assault,” he said.

One consequence of charging strangulation assaults as felonies is that a defendant may be more interested in pleading guilty to a lesser assault charge in order to avoid a possible felony conviction and the penalties it carries, Rushlau said. That at least gets that person onto the radar of the justice system and can mean more safeguards to protect victims.

Charging strangulation as a felony also sends a message to an offender, as well as to law enforcement, about the seriousness of the offender’s conduct. A Class B felony is punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

After the assault charge against Zedric Joseph, in which he was accused of squeezing his girlfriend’s neck on two separate occasions, Joseph pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct and served 48 hours in Penobscot County Jail. Under the student and athletic disciplinary codes, he was suspended and required to undergo counseling. He participated in a domestic violence program on campus and was reinstated.

After Joseph was charged with murder in West Palm Beach, Florida, during spring break, university officials defended the lack of punishment against him, saying there were no red flags in his behavior that might have hinted at murder.

Colpitts said strangulation should have been that red flag.

“It’s in your face, an eye-to-eye encounter,” she said. “One victim said ‘I could see my death in his eyes.'”

For more information go to: mcedv.org or call 1-866-83-4HELP(4357).

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.