“Can we talk?”

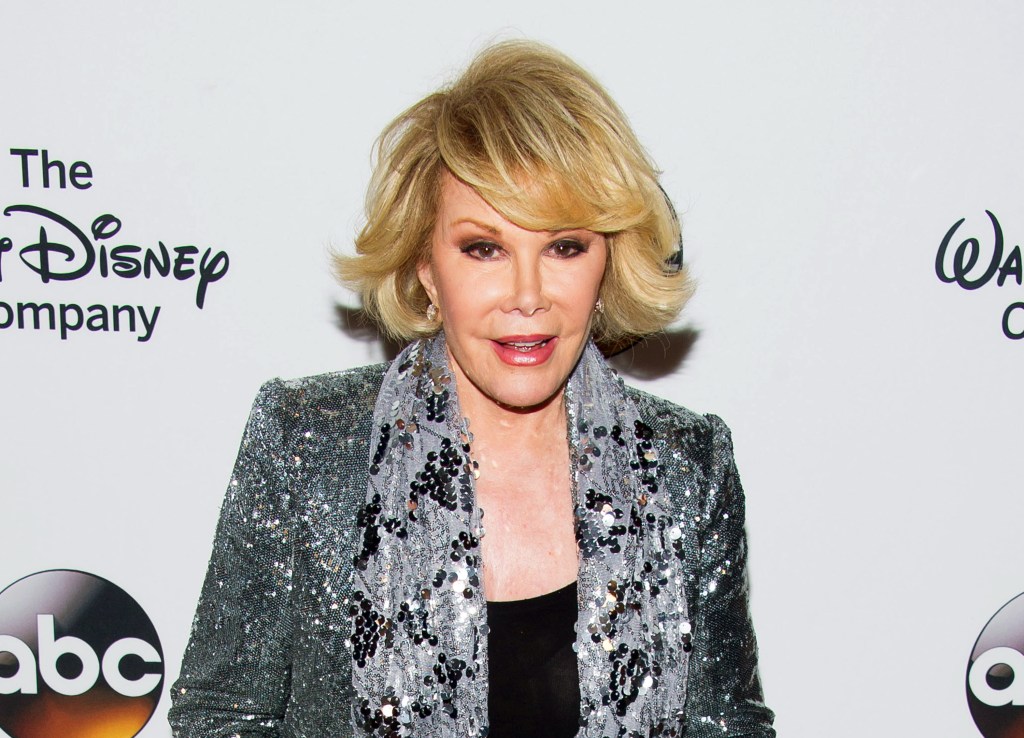

From the artificially plumped lips of Joan Rivers, it was an invitation, even a provocation, to join her on the uncensored comedic romps that made her one of the most popular and transgressive comedians of her era.

Decades before Comedy Central aired the rants of Sarah Silverman, and at a time when much of society considered comedy unbecoming of a lady, Rivers was telling jokes about her erogenous zones and sex life.

“On our wedding night,” she quipped, “my husband said, ‘Can I help you with the buttons?’ I was naked at the time.”

Celebrities, particularly the actress Elizabeth Taylor when she put on weight, were frequent targets. “When she pierces her ears,” Rivers quipped, “gravy comes out.” Queen Elizabeth II, the formidable but not always fashionable English monarch, she observed, wore “gowns by Helen Keller.”

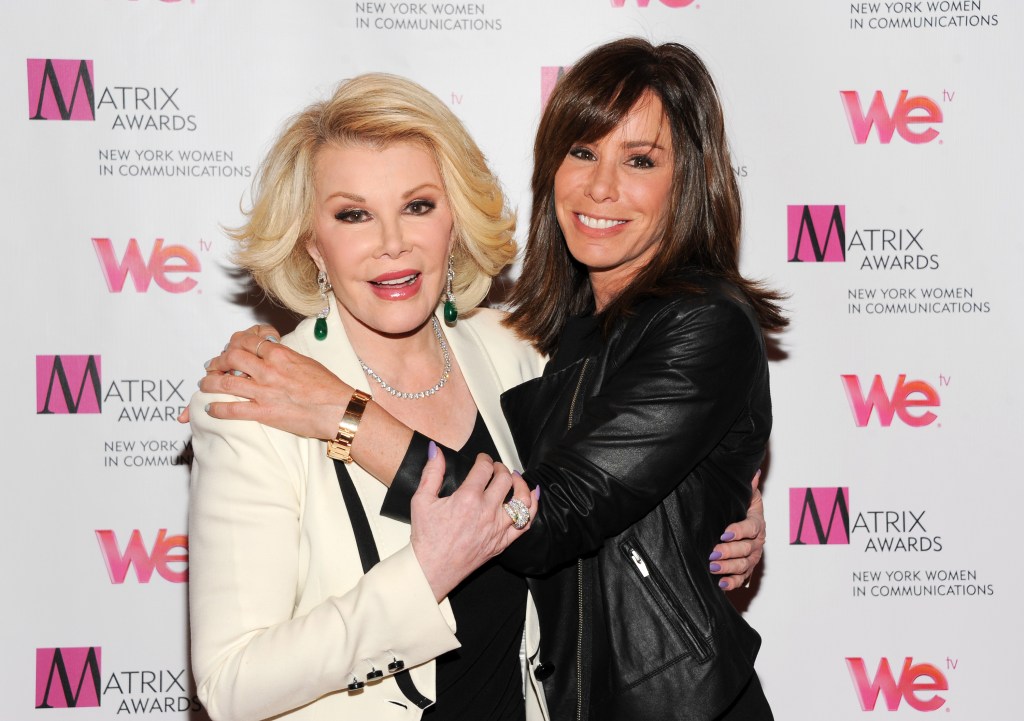

Over the years, Rivers’s comedic mean streak turned off some audiences while drawing in others — notably when she and her daughter, Melissa, cattily opined on celebrity fashion during their trademark red-carpet interviews for the E! cable network at the Academy Awards, the Golden Globes and other events. “Who are you wearing?” was a frequent line.

But Rivers joked as fiercely about herself as she did about others.

“I wish I had a twin,” she remarked, “so I could know what I’d look like without plastic surgery.” The image of her tightly stretched face, she speculated, could be shown to death-row inmates “to get their minds off women.”

Rivers, who was enjoyed or endured by the millions who watched her routines during her five decades as a television, radio and comedy-club performer, died Sept. 4 at a hospital in New York City, her daughter, Melissa Rivers announced. She was 81 and was hospitalized last week after going into cardiac arrest following a routine medical procedure.

Rivers was not the first female comic to become a household name; Phyllis Diller and others went before her. But she was among the first mainstream funny women to go dirty.

“She was very clever, quick, smart, appealing,” said Gerald Nachman, a historian of humor and the author of books including “Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s.”

She also was aggressive. “Something in her,” Nachman said, “made her feel that to keep up with the times, or to keep up with stand-up comedy,” that was how she needed to be onstage.

Rivers had entered show business in the 1950s over the objections of her parents, Jewish immigrants from Russia who had sent their daughter to Barnard College, the all-women’s school not known for producing raunchy comediennes. (She later would poke fun at her heritage. “A Jewish porno film,” went one joke, “is made up of one minute of sex and six minutes of guilt.”)

After a false start as an actress, Rivers turned to stand-up comedy, a form of employment that landed her in a series of unseemly clubs. But it provided a release for her unforgiving and seemingly endless social observations.

Comedy would carry her through professional setbacks, most notably her public falling out with “Tonight Show” host Johnny Carson, and personal tragedy, including the suicide in 1987 of her husband, Edgar Rosenberg.

“My comedy is about telling the truth,” Rivers once told an Australian interviewer. “My big thing originally was to say, ‘Can we talk?,’ meaning, can we tell the truth?”

Rivers’s break came in 1965 with an appearance on “The Tonight Show,” NBC’s long-running and highly watched late-night program then hosted by Carson. She had auditioned for the program seven times before she got a spot, and Carson was completely won over by her routine. “You’re gonna be a star,” she recalled his saying on the air.

Rivers returned as a guest and a regular substitute host and, in 1971, became the first woman to fill Carson’s chair for a full week while he was on vacation.

In the late 1980s, largely on the basis of those performances, the newly formed Fox Broadcasting Co. made major entertainment news by engaging her to host “The Late Show,” a program intended to compete with “The Tonight Show.”

Critics accused Rivers of betraying the program that had propelled her to fame. Her supporters insisted that if she were a man, Rivers would have been cheered on for taking the challenge.

By all accounts, her relationship with Carson never recovered.

“The first person I called was Johnny,” she wrote in the Hollywood Reporter in 2012, recalling the conversation in which she told Carson about her show on Fox. “He hung up on me — and never, ever spoke to me again. And then denied that I called him. I couldn’t figure it out. . . . I think he really felt because I was a woman that I just was his. That I wouldn’t leave him.”

In a matter of months, when the Rivers show’s ratings failed to meet expectations, Fox ended her run. It was a devastating blow to Rivers and her husband, who was the show’s executive producer and who was already weakened from a heart attack several years earlier. He overdosed on pills in a Philadelphia hotel room.

In her sorrow, Rivers called on comedy for relief.

“My whole life has been so horrendous this year,” she said at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas after Rosenberg’s death. “Thank God my husband left in his will that I should cremate him and then scatter his ashes in Neiman Marcus. That way he knew he would see me five times a week.”

Rivers later hosted the syndicated “Joan Rivers Show,” for which she received a Daytime Emmy in 1990. She was a headliner at high-end venues where she doled out the thousands of jokes that she had recorded and organized in cross-referenced files. A secretary noted in the files where and when each joke had been delivered so that Rivers’s act might never appear stale.

At times, she displayed what appeared to be an intense need to maintain her celebrity. In addition to her co-hosting duties with her daughter, Rivers formed a jewelry company that, through a bad business dealing, was reported to have left her $37 million in debt. She sold her jewelry on QVC.

“I don’t want sympathy audiences,” she had told People magazine after her husband’s death. “It’s my job to make them laugh, and I’m a professional. . . . Besides, I’m too short to be a tragic figure.”

Joan Alexandra Molinsky was born June 8, 1933, in Brooklyn. Her mother and her father, a physician, had what was described as an unhappy marriage and were terrified, their daughter said, of being poor. They raised her in Larchmont, N.Y. — a place, she said, where “a bush is a shrub, a porch is a terrace and everyone hides their wedgies.”

Rivers — Rivers was a stage name — showed early interest in show business and had an uncredited role in the 1951 movie “Mister Universe” with Bert Lahr and Vince Edwards. Three years later, she graduated from Barnard with an English degree.

Her other movie roles included a brief appearance as a party guest in “The Swimmer” (1968), based on the John Cheever story, and as the voice of the robot Dot Matrix in Mel Brooks’s comedy “Spaceballs” (1987).

Early on, she worked in publicity for the Lord & Taylor department store and as a fashion coordinator for the Bond clothing retailer, where she met her first husband, James Sanger. Their brief marriage was reportedly annulled.

She said that she turned from acting to comedy “because in those crummy clubs I could be comfortable and endure the rejection.” In the early years of her career, she adopted the stage name Pepper January in an act, the Times reported, that “got her fired from some of the least dignified strip joints in the country.”

“I humbled myself before sleazy agents,” she was quoted as saying, “the kind of people who shed their skins every year.”

Her fortunes changed when she wrote to and was signed by the agent Roy Silver. Silver helped her get jobs writing material for Phyllis Diller, whom she credited as a major influence, as well as Zsa Zsa Gabor and Bob Newhart. He also helped arrange her 1965 appearance on “The Tonight Show,” which led to more TV bookings as well as record albums.

Rivers ventured into Broadway, writing the short-lived comedy “Fun City” with Rosenberg and Lester Colodny. She helped write the popular TV film “The Girl Most Likely To . . .” (1973), a comedy starring Stockard Channing about an unattractive woman who undergoes plastic surgery and then seeks revenge on those who had previously been unkind to her. The 1978 film “Rabbit Test,” which she directed and co-wrote and which starred Billy Crystal as a man who becomes pregnant, received poor critical reviews.

She was nominated for a Tony Award in 1994 for her leading role in “Sally Marr . . . and Her Escorts,” a play, which she co-wrote, about the mother of comic Lenny Bruce.

Rivers’s books sold millions of copies and captured her style and bite in their titles. They included “Enter Talking” and “Still Talking,” both memoirs; “The Life and Hard Times of Heidi Abramowitz,” about the fictional tramp of her monologues; “Men Are Stupid . . . And They Like Big Boobs,” a guide to plastic surgery; and “I Hate Everyone . . . Starting With Me.”

She was the subject of the 2010 documentary by Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg, “Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work.”

Besides her daughter, survivors include a grandson.

Shortly before his death, Edgar Rosenberg said in an interview with The Washington Post that his wife was profoundly different from what many of her audiences assumed her to be.

“Very few people seem to make a distinction between her on- and offstage personalities,” he said. “I don’t know why that is. Nobody thought Jack Benny was stingy offstage. But Joan is a shy, introverted family woman, a very good mother and a wonderful wife.”

Rivers once explained the draw of comedy.

“The conventional diagnosis of comics,” she wrote in a memoir, “holds that they are hypersensitive, angry, paranoid people who feel somehow cheated of life’s goodies and are laughing to keep from crying. I agree, but think comedy is more aggressive than that. It is a medium for revenge.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.