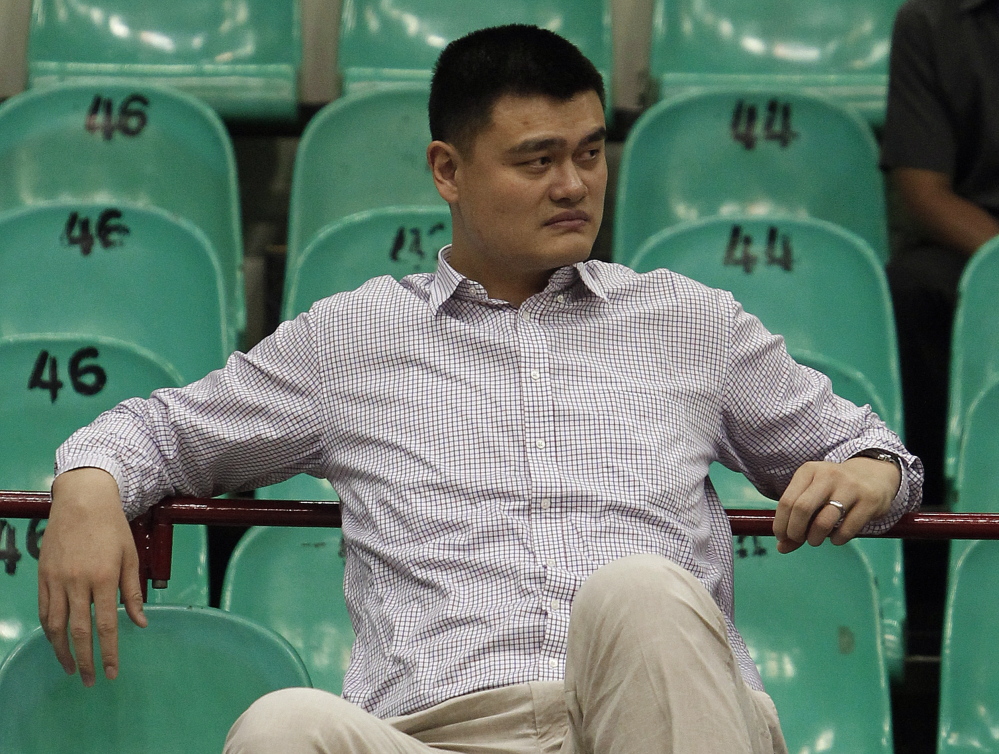

BEIJING — As a shy, nervous 22-year-old NBA rookie, Yao Ming confronted the concentrated power of Shaquille O’Neal for the first time – and came out a winner.

Now, more than a decade later and long retired from the game, the former Houston Rocket faces a challenge perhaps as daunting as it is radically different: to wean the Chinese nation off its love of ivory, and save Africa’s dwindling elephant population.

In the past three years alone, about 100,000 elephants have been poached for their tusks, according to a new study – a mass slaughter propelled by an ever-rising Chinese demand for ivory from an ever-richer nation. Yet the player once nicknamed the “Great Wall of China” aims to stop that flood, through the power of persuasion.

The metaphors are perhaps too easy: basketball’s gentle giant aiming to save Africa’s gentle giants; the man who built a bridge between China and the United States now trying to bridge another vast cultural divide, between his nation’s nouveau riche and the people and animals of Africa.

The 7-foot, 6-inch Yao, 33, said in a recent interview that he had connected with Africa particularly because “many animals there are bigger than me.”

Yao visited Africa for the first time in 2012 to see for himself the raw reality of elephant and rhino poaching. A documentary shown in China in August and scheduled to be shown in the United States in November shows the usually impassive Yao choking back tears as he towers above an elephant’s rotting carcass, its face brutally ripped off to remove its tusks.

“Before that, it was more of a number for me: How many tons of ivory, how much money comes out of this business. Sometimes the number is cold,” he said. “After you visit Africa, it is very unique. I felt that I built some kind of special connection with the animals.”

Yao’s transformation from basketball center to wildlife activist began in 2006, when he first met with staff members from WildAid, a San Francisco-based charity, during another injury-plagued season in the NBA. The activists soon persuaded the man who began his career with the Shanghai Sharks to join their campaign to save the world’s actual sharks, by pressing the Chinese people to give up shark fin soup.

Since then, Yao has appeared in a string of commercials and made countless public appearances to ram home the bloody reality of the global shark-finning industry, to show his fellow citizens how Chinese demand has been wiping out some of the ocean’s most elegant creatures, and to convince them that serving the dish at weddings and banquets is not a sign of sophistication but of ignorance.

Incredibly, implausibly, Yao and WildAid may have pulled it off. In part as a result of an anti-corruption campaign in which the costly delicacy was banned at government banquets, shark fin soup is falling out of fashion. A WildAid study released in August showed prices and sales of shark fins in China down by 50 percent to 70 percent.

But the carving of ivory is perhaps an even more deeply rooted tradition in China, and as wealth has grown, so has the fashion for giving lavishly carved pieces to business associates and friends as gifts. Although China allows a small, legal trade in ivory from old stockpiles, this provides the cover for a vast, illegal trade that has fueled a new wave of poaching in Africa, experts say.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.