A man who flew from Liberia to Dallas this month was diagnosed with Ebola on Tuesday, becoming the first person to board a passenger jet and unknowingly bring the disease here from West Africa, where it has killed thousands of people in recent months.

Experts have said that such an event was increasingly likely the longer the epidemic rages in West Africa. But health officials were quick Tuesday to tamp down any hysteria, emphasizing the ways in which the U.S. medical system is well equipped to halt the spread of the disease.

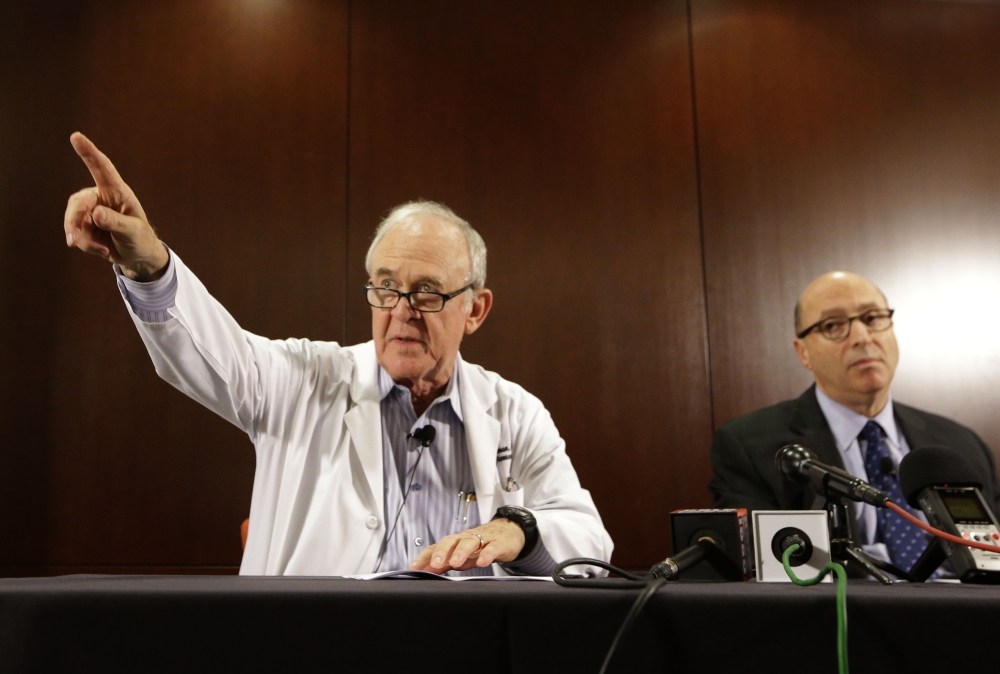

“We’re stopping it in its tracks in this country,” Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a news conference Tuesday afternoon.

The infected man, who was not identified, left Liberia on Sept. 19 and arrived in the United States the following day to visit family members.

Health officials are working to identify everyone who may have been exposed to him since he began showing symptoms last week. Frieden said this covered just a “handful” of people, a group that will be watched for three weeks to see if any symptoms emerge.

“The bottom line here is that I have no doubt that we will control this importation, or this case of Ebola, so that it does not spread widely in this country,” Frieden said. “It is certainly possible that someone who had contact with this individual could develop Ebola in the coming weeks. But there is no doubt in my mind that we will stop it here.”

People who traveled on the same planes as this man are not in danger because he had his temperature checked before the flights and was not symptomatic at the time, Frieden said. Ebola is only contagious if the person has symptoms, and can be spread through bodily fluids or infected animals but not through the air.

“There is zero risk of transmission on the flight,” Frieden said.

There were more than 6,500 reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone as of Tuesday, and the crisis has been blamed for more than 3,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Ebola was first identified in 1976, and the current outbreak in West Africa is considered the largest and most complex in the history of the virus, with more cases and deaths than every other outbreak combined.

Until now, the only known cases of Ebola in the United States involved American doctors and aid workers who were infected and returned to the country for treatment. All have survived.

One of them, Richard Sacra, was discharged last week from a Nebraska hospital. Days later, the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland admitted an American physician who was exposed to the Ebola virus in Sierra Leone. There were reports of possible Ebola patients in New York, California, New Mexico and Miami, but all of them tested negative for the virus.

The unidentified person with Ebola is being treated in intensive care at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, according to Edward Goodman, the hospital’s epidemiologist.

From television to Twitter, Tuesday’s news made the distant health crisis seem like something that could appear almost anywhere. But experts said it was hard to imagine that Ebola would not find its way across other borders – a CDC estimate recently projected more than a million people in West Africa could be infected by January if left unchecked.

“It was inevitable once the outbreak exploded,” said Thomas Geisbert, a professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, who has researched the Ebola virus for decades. “Unless you were going to shut down to shut down airports and keep people from leaving 1/8West Africa3/8, it’s hard to stop somebody from getting on a plane.”

But Geisbert quickly underscored how unlikely the virus is to spread in the United States. For starters, he said, officials placed the sick man in quarantine quickly in order to isolate him from potentially infecting others. In addition, health workers are already contacting and monitoring any other people he might have had contact with in recent days.

“The system that was put in place worked the way it was supposed to work,” Geisbert said.

That doesn’t guarantee that no one else will get infected, because the sick person could have transmitted the disease to someone else before being isolated. But that approach almost certainly ensures that the United States will quickly contain the disease. In addition, while there is no approved treatment for Ebola, hydration and other basic medical care is far better in the United States, making it more likely infected patients will survive.

President Barack Obama spoke with Frieden on Tuesday afternoon about the patient and the efforts to seek out any potential other cases, the White House said.

At a press briefing later in the day, Frieden said that the infected man did not develop symptoms until about four days after arriving in the country. He sought medical care on Sept. 26 but was sent home. He was admitted to the hospital two days later and placed in isolation, but it remained unclear Tuesday how many people he might have encountered during that period when he was contagious. Frieden, who would not say if the man was a U.S. citizen, said the man is not believed to have been in the response to the Ebola outbreak.

David Lakey, head of the Texas Department of Health Services, said the state’s laboratory in Austin, Texas, received a blood sample from the patient on Tuesday morning and confirmed the presence of Ebola several hours later. This laboratory was certified to do Ebola testing last month.

The deadliest Ebola outbreak in history is centered in the West African countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, though there is a separate outbreak in Congo. The affected countries have fragile or barely existent health care systems, people are being turned away from treatment centers, and family members are caring directly with those sick and dying from Ebola.

For months, the CDC has been conducting briefings for hospitals and clinicians about the proper protocol for diagnosing patients suspected of having the virus, as well as the kinds of infection control measures to manage hospitalized patients known or suspected of having the disease. Many procedures involve the same types of infection control that major hospitals are already supposed to have in place.

Early recognition is a critical element of infection control. Symptoms include fever greater than 101.5 degrees Fahrenheit, severe headache, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea and contact within 21 days before onset of symptoms with the blood or other bodily fluids or human remains of someone known or suspected of having the disease or travel to an area where transmission is active.

The CDC also has scheduled more training for U.S. workers who either plan on volunteering in West Africa or want to be prepared in the event that cases surface at their own hospitals.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.