Four University of Southern Maine students may lose thousands of dollars in research fellowship funds from a NASA-related program because USM is closing several research labs, officials and students say.

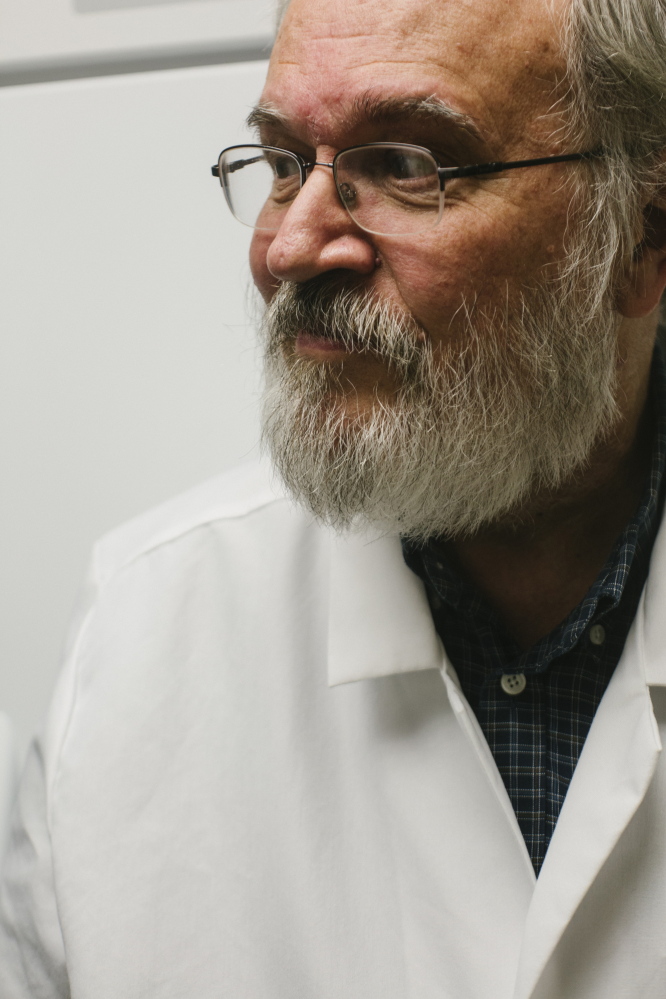

“I am absolutely livid,” said Jillian King, a graduate student awarded $6,000 through the NASA/Maine Space Grant Consortium Fellowship Program to study viruses as part of her thesis project. King’s adviser, virologist S. Monroe Duboise, said he is equally frustrated at the move, one of several ripple effects of the university’s decision two weeks ago to end the applied medical sciences graduate program.

University of Maine System trustees have voted in the past two months to cut four other USM academic programs – the undergraduate French major, the American and New England studies graduate program, the geosciences major, and the arts and humanities major at USM’s Lewiston campus.

USM President David Flanagan said the elimination of those programs, and of 50 faculty positions, will shave $6 million off a budget gap of $16 million for the 2015-16 fiscal year. Critics have repeatedly questioned what happens to students in the five eliminated programs, and to other students who planned to take courses that had been taught by the eliminated faculty. USM officials have said other faculty, and part-time or adjunct faculty, will teach those courses.

But losing fellowships that have already been awarded to students shows the consequences of the cuts, Duboise said.

“This action is one more piece of a growing body of evidence that there may be no real administration intention to keep good faith with students in their pursuit of the educational opportunities that brought them to USM,” Duboise wrote in an email, referring to the administration’s responsibility to ensure that all current student majors in eliminated programs can finish their studies in what is known as a “teach-out” plan.

In addition to King, three undergraduate biology majors were awarded $3,000 fellowships to work in labs that will be shut down at the end of the year, said Samantha Langley-Turnbaugh, associate vice president for academic affairs in charge of research.

She said Wednesday that officials were trying to find alternative mentors and projects for those students to try to save the fellowships.

King’s case is different, she said, because the school must give her the opportunity to complete her graduate degree in applied medical sciences.

“I know the students are very anxious,” she said, acknowledging that there are no alternative USM labs or professors in certain fields. Duboise, for example, is the only virologist on campus.

“We certainly don’t have any depth at USM, but certainly an industry mentor could be a possibility, or Duboise could remain to teach some students out,” Langley-Turnbaugh said. “The dean is working on it as fast as he can.”

One of the undergraduate students, Danny Tomkinson, said his fellowship is specifically tied to research on viruses in Duboise’s lab, and he doesn’t think he can change that and still keep the fellowship. No one from the biology department has contacted him to discuss what happens when they close the lab.

“I have the letter that I got the grant,” he said. “I haven’t gotten anything else, so as far as I know I can get started.”

The applied medical sciences program, with five faculty members, had 16 majors and 54 graduate and undergraduate students enrolled this fall. All five faculty members will be gone by Dec. 31. The program offers courses in immunology, molecular biology, genetics, toxicology and epidemiology to prepare students for doctoral work and careers in biotechnology, biomedical research and public health.

Several biotechnology executives in the Portland area have vigorously objected to closing the program, saying they rely on the applied medical sciences students and graduates for research and potential employees.

“It’s going to be a hard loss for us,” Joe Chandler, president of Maine Biotechnology Services, told trustees when they were considering the cuts.

On Wednesday, a NASA Ames Research Center astrobiologist who has worked with Duboise for more than eight years through the Maine Space Grant Consortium was visiting his lab, and said she was sorry to hear it would be shut down.

“This has been a really nice collaboration,” said Lynn Rothschild, reminiscing with Duboise about joint projects, from field work they did together in Africa to teaching students at three Maine high schools about weather balloons. “Having hands-on projects is so important to get kids excited about science.”

Duboise’s work with viruses is also important, Rothschild said. “When Ebola is on the front pages, I’m glad to know the next generation is being trained in virology,” she said.

Duboise, an associate professor of molecular biology and microbiology, said he was still hoping to figure out a way to continue his work. “I refuse to consider it a done deal, because it makes so little sense,” he said.

Just two years ago, Duboise was awarded the University of Maine System Trustee Professorship, a special program that allowed him more time and resources to work on developing an anti-malaria vaccine, research partly funded by a Bill & Melinda Gates grant.

Shutting down his lab in a few weeks is almost impossible, he said.

“I don’t think they have a clue about what it takes to be a scientist and run a research program. You can’t just shut it down in weeks. Even a year would be rushed,” he said.

For King, who graduated from UMaine-Augusta in May, canceling the NASA fellowship puts not only her thesis project – and degree – in jeopardy, but is a financial blow for the single mother who has already spent “a significant amount of time” researching and preparing for the project.

Her work in the lab, combined with tuition waivers and being a graduate assistant, are all tied together.

“That is how I make being a mom and being a student work,” King said.

She’s also frustrated that no deans or administrators have contacted her.

King got a letter Oct. 23 on USM letterhead, telling her she had received the award and spelling out the details of the project. The consortium generally gives USM about $25,000 a year, and allows the research administrators on campus to solicit and select which students get fellowships.

Langley-Turnbaugh said the faculty member who made the selections this year didn’t know the labs and graduate program were going to be eliminated.

King said she learned there was a problem when she emailed the department to find out how to fill out some fellowship paperwork. She received a two-sentence email from a department administrative assistant saying that USM “could not approve” the award because the program was being eliminated. The email directed her to talk to Duboise or other professors “to see if an alternative arrangement with another mentor might be possible for you.”

King and Duboise said shifting her project to another mentor is not practical, since her research project will be impossible if the lab and Duboise are both gone.

Duboise criticized the “truly regrettable” situation in an email he sent to some colleagues.

“The fact that the new interim administration at USM orchestrated a distorted, rushed, and mistaken attack upon (applied medical sciences) and the USM research community has not ended any of my research and education collaborations,” Duboise wrote. “The UMS board of trustees and USM continue to have obligations to see that students are not deprived of the educational and research opportunities that they have sought and indeed earned.”

King said she was particularly upset that the email she received suggested she was responsible for figuring out how to move forward by herself.

“The administration made this cut and they should be the ones responsible for finding a solution,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.