Marine scientists see the collapse of local shrimp stocks as part of a global pattern reflecting the impact of rising sea temperatures.

Regulators canceled the Maine shrimp season Wednesday, citing dwindling shrimp populations in the Gulf of Maine. But the implosion of northern shrimp stocks here is part of a larger trend across the North Atlantic. Stocks within fishing grounds from Labrador to Norway are in sharp decline, indicating that warming ocean temperatures are affecting the species’ abundance and ability to reproduce, according to fishery biologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Populations of northern shrimp, a cold-water species, are down across their range, including in the Flemish Cap, Newfoundland’s Grand Banks, and waters off Greenland, Iceland and southern Norway, said Anne Richards, a fishery biologist at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Richards serves as an adviser to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which met in Portland to cancel the upcoming winter shrimp season for the second year in a row. Regulators say the region’s population of northern shrimp in the Gulf of Maine plummeted from 2011 to 2012.

“All of a sudden, everything was gone,” Richards said. “It was almost like a vacuum came and sucked up all the shrimp.”

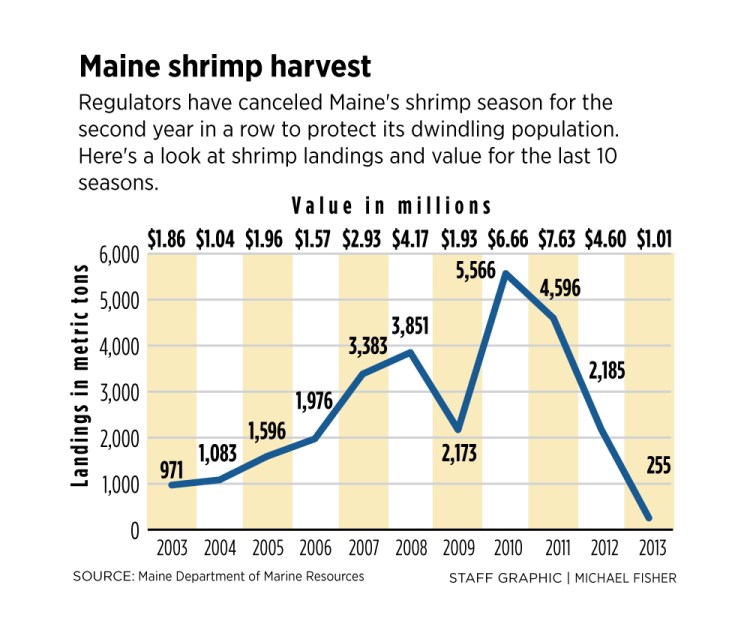

A small but valuable part of the state’s fishing industry, shrimp landings were valued at $1.01 million in 2013, down from $6.6 million in 2010, the last year there was a healthy harvest. Maine fishermen typically catch 85 percent to 90 percent of the annual harvest in the Gulf of Maine. The shrimp, which are small and sweet, are a popular food in New England.

Once plentiful, the shrimp population in the Gulf of Maine is at record-low levels. Its population this year is estimated to be at only 3 percent of the average population going back to 1984, when scientists began monitoring the species.

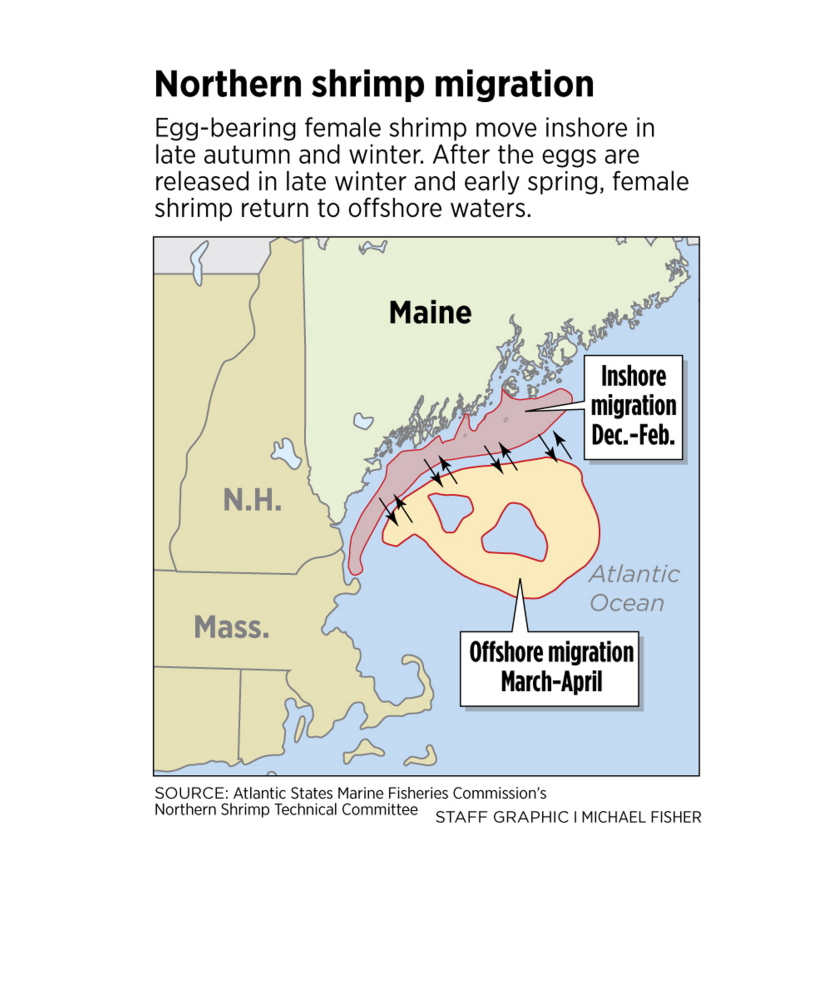

At the same time, the sea surface temperature on the coast of Maine in February and March, when female shrimp release their eggs, has increased. In Boothbay Harbor, where scientists have been recording sea temperatures since 1905, the average temperature in 2010 to 2012 – years with poor shrimp larvae survival rates – was 39.5 degrees, 2.5 degrees warmer than the average temperature from 1984 to 2009.

Shrimp are notoriously sensitive to water temperature, and the Gulf of Maine population, which inhabits an area stretching from Cape Ann, Massachusetts, to Penobscot Bay, is at the southern end of the species’ range.

Richards said it’s unclear how warming water temperature affects shrimp reproduction rates, but she suspects it’s connected to the timing of plankton blooms. Northern shrimp hatch their eggs to coincide with the release of springtime plankton blooms, which provide larvae with a ready food source. If warming water temperatures cause those two events to be out of sync, larvae have no food, Richards said.

Nearly all scientists studying changes in the world’s climates say that warming temperatures are caused by the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas.

Because of their small size, short life spans and sensitivity to temperatures, shrimp serve as a “canary” of global warming, said Andrew Pershing, an oceanographer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute.

He said the Gulf of Maine, the Grand Banks off Newfoundland and the waters off Norway – which also have seen declines in shrimp populations in recent years – have warmed up faster than the rest of the ocean.

The Gulf of Maine has been warming at a rate of 0.09 degrees annually over the past 50 years, but in the last decade the warming has accelerated and is nearly half a degree (0.50) annually, he said.

While female northern shrimp may live up to five years, lobsters can live to be 50, so the impact of warming temperatures on lobster populations takes longer to become apparent, Pershing said.

“They can hunker down and wait it out,” he said.

Richards said the increased number of northern shrimp predators, such as spiny dogfish and redfish, also may play a role in declining shrimp populations.

She said it appears that shrimp populations are being “squeezed in both directions,” with larvae dying for lack of food and adult shrimp getting eaten by predators.

Marine scientists from other northern nations need to work together to better understand the relationship between warming ocean temperatures and shrimp populations, she said.

Maggie Hunter, a scientist and shrimp specialist at the Maine Department of Marine Resources, suspects that the warming temperatures are to blame for the population’s collapse.

“They are in the southern part of their range,” she said. “You might expect them to be one of the first stocks to be affected if the gulf is warming, which it is.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.