UNITED NATIONS — The Ebola epidemic and the war in Syria have cast a spotlight on the inadequacies of the United Nations as it tries to operate in a globalized world with a power structure that hasn’t changed since 1945.

To many who know the U.N. well, the organization has grown bloated with age, is underfunded and shows few signs of righting itself. That was evident when an internal report by the U.N. health agency revealed that cronyism and incompetence in its leadership may have contributed to the spread of Ebola.

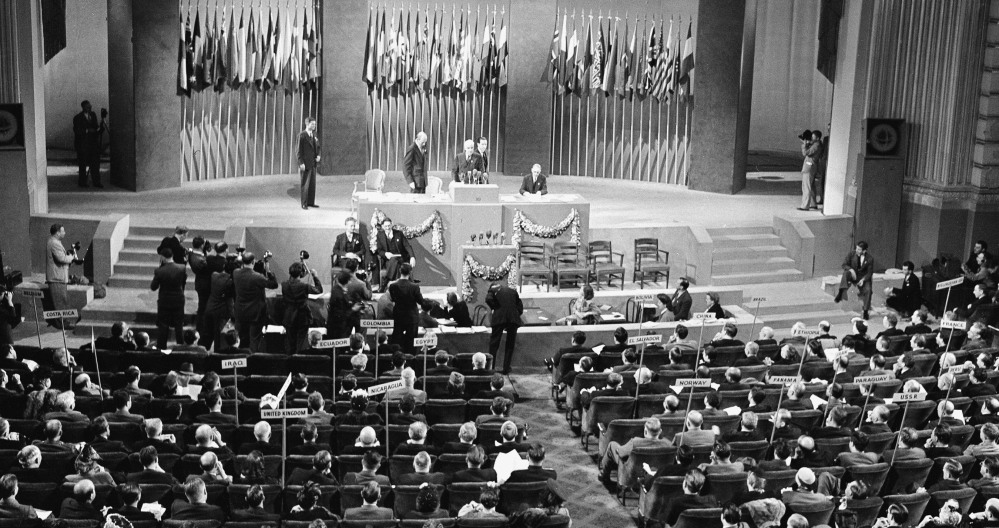

Since the U.N. was born after World War II, it has grown from 51 members to 193. As it approaches its 70th anniversary next year, it is hobbled by bureaucracy, politics and an inability among its five most powerful members to agree on many things – including how to bring peace to Syria.

“If you can imagine any big multinational corporation keeping its structures the same as in 1945, it would have been destroyed by now in the marketplace,” said Patricia Lewis, a nuclear physicist who led the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research.

POWER STRUGGLES

The paralysis shows in the debate over what the U.N. itself should be. Most nations agree that the 15-member Security Council – the U.N.’s most powerful body – must adapt to address threats to international security. Yet all reform proposals are repeatedly rejected.

“Those who wield the power don’t want to lose the power and they don’t want to share it,” said Lewis, who is now at the Chatham House think tank in London.

The five permanent members of the council who can cast vetoes – the U.S., Russia, China, Britain and France – ultimately call the shots.

One result is that Russia, a close ally of Syria, has blocked all Western resolutions that would pressure President Bashar Assad to end the conflict there.

Certainly the U.N. has had some success in its primary mission to stop “the scourge of war.” A record 130,000 U.N. peacekeepers are deployed in 16 hotspots, and it has responded to an unprecedented four simultaneous, top-level humanitarian crises: Iraq, Syria, Central African Republic and South Sudan.

U.N. spokesman Stephane Dujarric argues that the U.N. has adapted since its founding. He said Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has worked with member states “to make the system more flexible and even more responsive” to needs in many areas, including collective security, international transport, health and human rights.

But inefficiency, inaction and sometimes paralysis extend through a sprawling system that includes 15 autonomous agencies such as the World Health Organization; 11 other funds such as UNICEF; and numerous other bodies.

The secretary-general is the chief administrative officer, elected by the General Assembly with approval from the Security Council. The result: Secretary-generals may have an outsized role on the world’s stage, but they have little independent power and 193 bosses.

FUNDING SHORTAGES, CUTS

The members often fall short in funding the U.N. and owed about $3.5 billion in early November for regular operations and peacekeeping. Countries slashed the budget of WHO, the agency addressing the Ebola crisis, by nearly $600 million in 2011, and the U.S., its biggest contributor, has dropped its donation by at least 25 percent since then.

The WHO’s botched initial response to Ebola was blamed on a shortage of funds, overstretched staff and a dysfunctional organizational structure. A draft internal document obtained by The Associated Press in October describes how WHO country offices in Africa are led by “politically motivated appointments.”

Meanwhile, U.N. peacekeeping forces have been criticized for failing to protect civilians against attacks. Peacekeeping chief Herve Ladsous recently said his department is under the most severe strain since the U.N. was founded, pointing to the deaths of over 100 peacekeepers this year.

The agency’s human rights operation also faces problems: Although it is one of the U.N.’s three so-called pillars, along with development and peace and security, it gets only 3 percent of the regular budget.

The question now is whether the U.N. can change.

Stewart Patrick of the Council on Foreign Relations said that institutional reform is extraordinarily difficult in the absence of a major crisis.

“It may take something along the lines of an existential crisis or something as horrific as nuclear use or dramatic deterioration in the world’s climate, with potentially catastrophic cascading effects,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.