Hendrick Goltzius (1556-1617) is one of the most important European artists you have never heard of.

A towering figure in Dutch art, Goltzius was a printmaker, draftsman and publisher whose subjects included Italian sculpture as well as portraits, Biblical themes and other popular topics.

Because he was a publisher, engraver and artist who sold work directly in the public market at a time when art was typically commissioned by a patron, Goltzius’ art business uncannily mirrored contemporary cultural capitalism. He treated style as a portable commodity and participated directly in the open market in such a way that seems prescient of Pop Art. It may be our standard now, but it was possibly unique at the time.

But his extraordinary pictorial talent places him on a short list of the most important print artists from Western culture that includes Albrecht Dürer, Giambattista Piranesi, Rembrandt van Rijn, William Hogarth, Francisco de Goya, Honoré Daumier and, most notably, Winslow Homer. Homer became America’s best known and most influential artist because of his engravings that went out to millions via Harper’s Magazine.

Like Dürer, Goltzius was easily identifiable by his virtuoso hand – one that was particularly famous, however, because it was malformed in a way that allowed him remarkable control of the burin, or the steel engraving stylus with which he drew. Goltzius’ images have a technical sizzle that makes them fascinating to both connoisseurs of Old Master prints and contemporary audiences with our focus on the here-and-now object qualities of art.

In other words, Goltzius could draw like few ever could. And that is an easy thing to appreciate.

But he could also design beautifully during an age when composition was far more than the balance of visual elements on a page. It was about the appropriateness, complexity and narrative flow of the subject within and throughout the image. It was about scale – both real and imagined. And Goltzius was doing this at a time and place unlike any other in history, when the church dominated European politics, capitalism as we know it was in its infancy and artists were considered artisans rather than the entrepreneurial impresarios we see them as today.

Although he took up painting at middle age, Goltzius was primarily a printmaker. The stunning 1615 “Helen of Troy” may fool viewers into thinking that paint was his primary medium, but it was not. (While the glazing of the flesh is masterful, for example, the fabric falls short.)

One of Goltzius’ images in his “Life of the Virgin” series is the 1594 “Circumcision.” It shows a large, gothic church interior with dozens attending the sacrament. A hooded priest (reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Adam-touching Jehovah) holds the baby while the doctor attends to him. The doleful Virgin waits patiently behind the circle.

What the audience of the time would see, however, was a scene rendered in the exquisite hand of Dürer. And, in fact, the competitive Goltzius famously fooled specialists with this piece.

Goltzius was less interested in forgery than proving he could adopt and adapt the styles of (other) great artists for his own purposes. This is a post-modernist strategy centuries ahead of its time and, combined with his skills and market awareness, it made Goltzius unique.

This is a step away from the idea of making copy prints of famous designs – like when Goltzius would make engravings of his friend Bartholomeus Spranger’s paintings. And we even see Goltzius pushing the envelope of viewing perspective with his images of famous sculptures he saw in Italy, such as the “Hercules Farnese” or the “Apollo Belvedere” – which Goltzius would present as sculptures under the considering eye of visiting viewers or discerning, drawing artists.

His handling of the Pygmalion theme also goes further than expected: By asserting styles have lives of their own, the mannerist champion adds a new (and satisfying) twist to the mythological artist’s desire for his work to come alive and love him back. (Goltzius might have been a bit too confident that history would adore him.)

Goltzius’ best known sculptural image is his “Great Hercules” of 1589. It was itself made on a single, giant copper plate (22 inches by 15.75 inches) and features a preternaturally bulging figure that hearkens back to Bandinelli’s Hercules at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence that was criticized as a “sack full of melons” by none other than Benvenuto Cellini when unveiled in 1534. (We see the bodacious backside of Bandinelli’s colossus in other Goltzius images at Bowdoin – those blushworthy buttocks are hard to miss.)

Goltzius’ images are fascinating and entertaining enough that we get pulled into the details. Even casual viewers are likely to notice that Goltzius could vary the thickness of each line to create shading-like effects, and that he used the “dotted lozenge” technique in which a dot would be placed between crosshatched lines for similar reasons. What we can’t see here is that Goltzius was an inventor of the latter technique and that very few artists ever approached Goltzius’ control of lines.

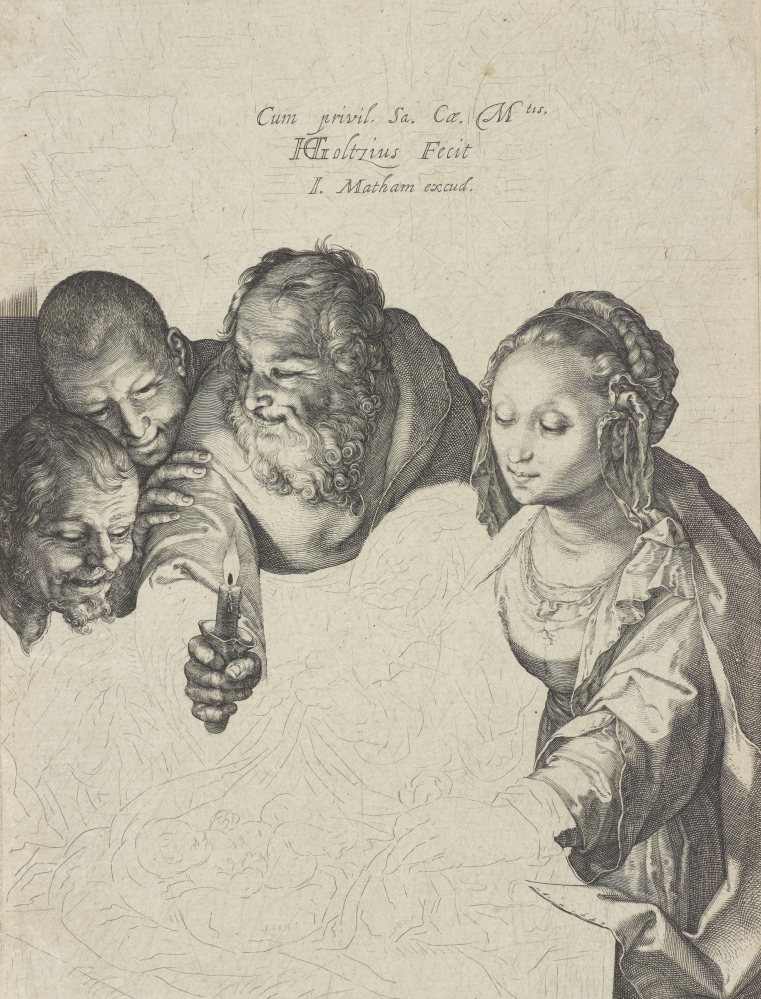

One of the most revealing images in the show is an unfinished “Adoration of the Shepherds” that picks up on the single-candle light source of Titian’s handling of the same scene. The unfinished image is a window into Goltzius’ process, but the sheer beauty of the work reminds us that something far beyond technique is happening before our eyes. This transportive, ineffable quality characterizes the exhibition.

The works on display reveal Goltzius’ teacher and his students as well as the political context of the day. They introduce his business model and his influential circle of friends. But, as much as they try to lure you away with intriguing ideas, it’s impossible to forget the composition, design and – more than anything else – the bravura line of this great Dutch artist.

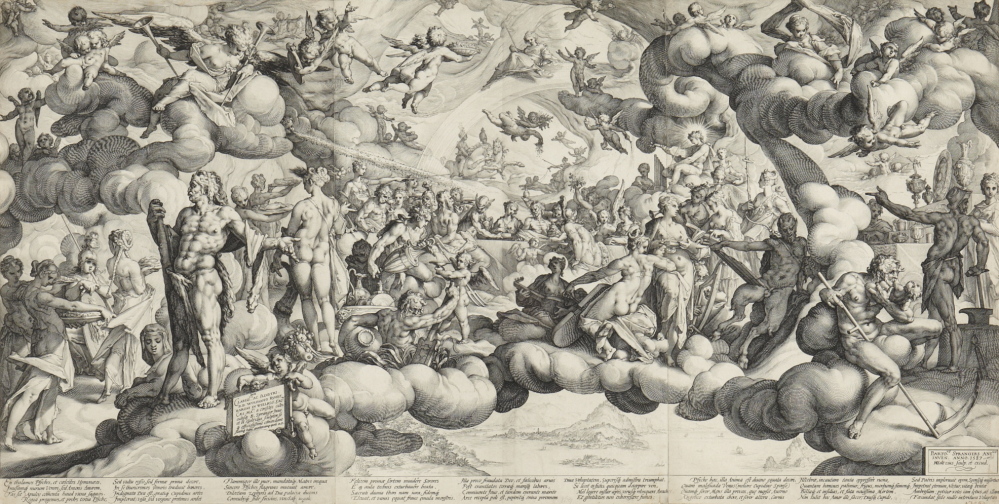

The one thing that may pull you away (at least momentarily) starts with Goltzius’ 1587 engraving “The Wedding of Cupid and Psyche” and its scores of celebrating celestial figures that comprise a virtual compendium of art historical high points. In the next room, the suite of tapestries illustrating Apuleius’ story of Cupid and Psyche, made after designs by the great Pieter Coecke van Aelst, provide the affluent bookend to Goltzius’ paper prints.

Coecke was another great Western artists. With the current, incomparably beautiful exhibition of his giant tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he may soon get his rightful applause.

Whether Coecke holds your attention or not, you will find yourself coming back to Goltzius again and again. Once you notice certain things, after all, you start to see them everywhere.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.