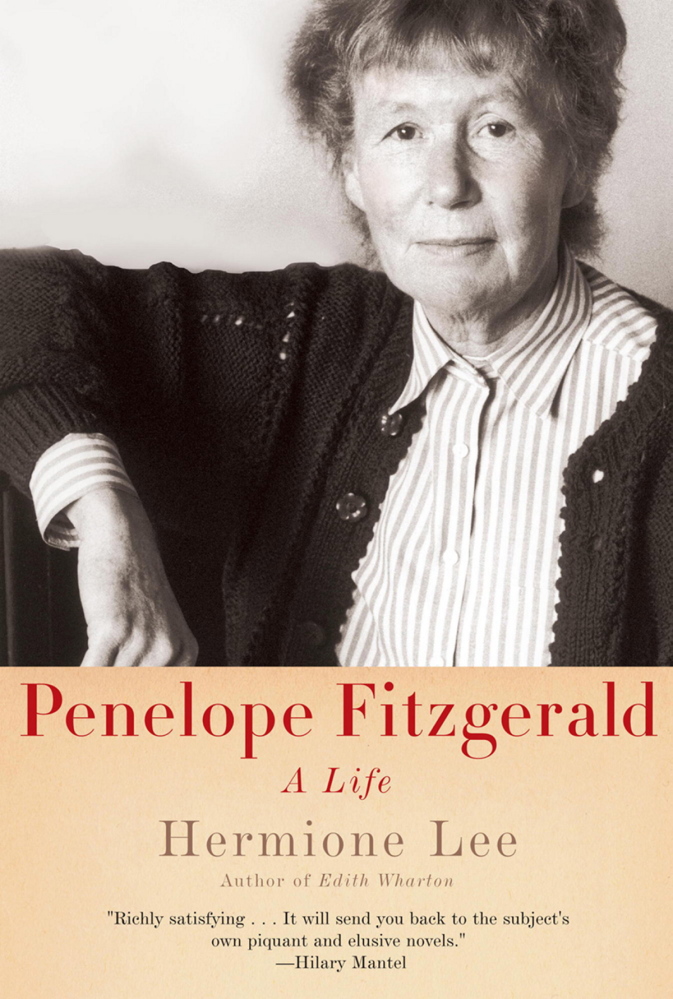

Hermione Lee’s sensitive, respectful biography traces the life of a woman as elusive and enigmatic as her fiction. Coming into public prominence when she was over 60, Penelope Fitzgerald often concealed her razor-sharp intelligence beneath a scatty exterior, inviting unwary journalists to think of her as the sort of vague old lady who always mislaid her keys. The wit, brevity and lucid prose of her novels, from “The Bookshop” in 1978 through “The Blue Flower” in 1995, similarly misled superficial critics into patronizing them as charming comedies of manners.

On the contrary, Fitzgerald commented, in a candid moment; she wrote about “the tragedy of misunderstandings and missed opportunities which I have done my best to treat as comedy, for otherwise how can we manage to bear it?”

She had ample experience of such tragedies – not in youth, when misunderstandings tend to be dramatic and temporary, but in middle age, when missed opportunities might well be gone forever.

Born Penelope Knox in 1916, she seemed in her 20s and 30s to be making brisk progress toward the brilliant success her formidably intellectual, high-achieving family expected. She graduated with highest honors from Oxford and in 1942 married Desmond Fitzgerald, a dashing lieutenant in the Irish Guards. By 1950, they were living in London’s “shabby-smart bohemian” Hampstead area, editing a well-regarded cultural/political monthly, World Review.

It all went smash in the decade following World Review’s 1953 demise. Having vividly captured the sparkling milieu of the rising young Fitzgeralds, Lee evokes with equal cogency the grim particulars of their descent. Desmond retreated into drink, Penelope retreated with their daughters to live on a Thames barge (inspiration for her 1979 novel, “Offshore”); it sank, and they wound up in a homeless shelter. It was during this bleak period, Lee suggests, that the erstwhile golden girl discovered her empathy for, in her own words, “people who seem to have been born defeated or, even, profoundly, lost.”

The Fitzgeralds reconciled and reordered their life on a much-reduced scale. Desmond worked as a travel agent until his death in 1976; Penelope held a series of underpaid teaching jobs, satirized in “At Freddie’s” (1982). She never complained; she was a loyal wife and a devoted (albeit exacting) mother determined to ensure that the Fitzgeralds’ financial problems did not mar their children’s prospects.

The stoicism she developed during a quarter-century of scheming to make ends meet served her well in dealing with the condescension that greeted her early novels. Lee rebuts reviewers who dismissed Fitzgerald as a lightweight by spotlighting her profound engagement in the world of art and ideas, sustained even in her most impoverished years.

Fitzgerald finally achieved the widespread critical acclaim she deserved in her 70s, after she turned from loosely autobiographical fiction to write four novels set in historical periods and grounded in intensive research. “Innocence” (1986), “The Beginning of Spring” (1988) and “The Gate of Angels” (1990) cemented her reputation as a writer whose superlative technical skills allowed her to convey penetrating insights into the human heart as much by what wasn’t said as what was; “she felt it insulted the reader to explain too much.”

“The Blue Flower,” her final masterpiece, galvanized her sales for the first time in America and won her a National Book Critics Circle Award at age 80.

Lee, who has sympathetically portrayed Fitzgerald throughout, takes evident pleasure in depicting the fulfilled and happy years before her death in 2000. Yet the most memorable portions of this unsentimental, moving biography chronicle decades of sorrow and struggle, making palpable the weight of experience Fitzgerald transmuted into fiction of such remarkable grace and deceptive ease.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.