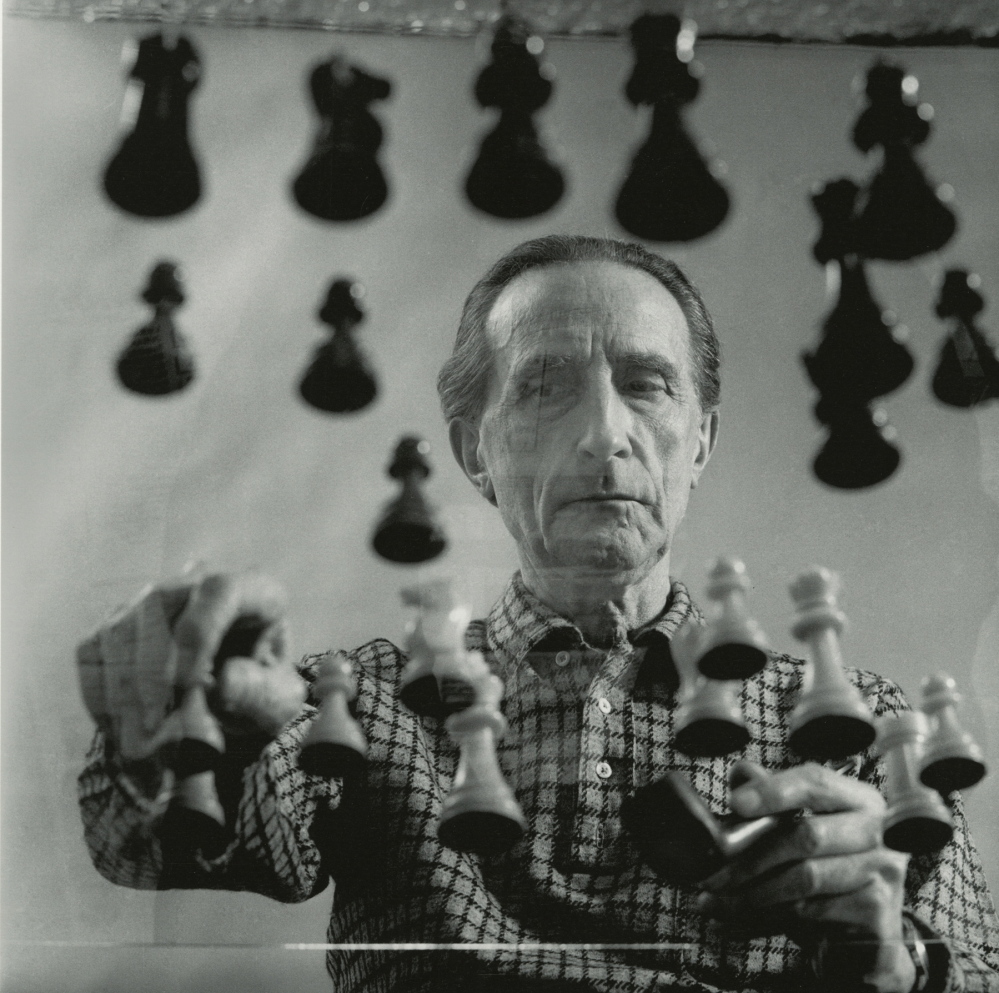

In 1956, Marcel Duchamp said: “The danger for me is to please an immediate public … I would rather wait for the public that will come 50 years – or a hundred years – after my death.”

Duchamp died in 1968, so in the spirit of Duchampian play, we still have few years. Or maybe he was right, and we are still too close. After all, there is little consensus about Duchamp.

Duchamp came to fame in America as his “Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2” came to the seminal 1913 Armory Show. Combining the logic of Eadweard Muybridge’s multiple image motion photography with Cubist style, the painting had already inspired controversy about hanging it in the Cubist section of the Salon des Indépendents in Paris – from which he famously withdrew it when painter Albert Gleitzes requested Duchamp paint over the title included in the work.

Because of all the academic ink spilled about him, Duchamp is more daunting to the public than he should be. But you do not have to know what has been said about Duchamp to enjoy and appreciate his art. If you are open to ironic wit, then Duchamp’s work can be fun and even hilarious.

Bowdoin College’s “Collaborations and Collusions in Modern and Contemporary Art” is a Duchamp exhibition. Its biggest flaw is that it is not clear at first what the show is about: You leave the first room, with its Picassos, Manets, Cassatts, Cézannes and minor printers, and only then find yourself in a Duchampian world. It would be a better show if its subject were clear from the start.

Still, it’s an excellent exhibition if you hunker down and follow the narrative that, whatever he claimed, Duchamp was not operating in a void and his artistic community involved everyone from his grandfather to his siblings, friends and colleagues. This idea is a game-changer: Instead of appearing like he was trying to mess with the audience, Duchamp seems dedicated to ideas shared amongst respected friends and colleagues. It shifts Duchamp’s irony from being wielded like a sword into a ploughshare used to break new ground.

The first important piece to the puzzle is Emile Nicolle, Duchamp’s maternal grandfather. As strong as Nicolle’s French architectural etchings are, they aren’t what you take away from the show’s first star-studded gallery. (If this introductory room’s role as preface were clearer, the exhibition would be stronger.) Then among Duchamp’s work, which essentially revolves around his portable vanity museum “Boîte en-Valise (Box in a suitcase),” we find the work of his brothers Jaques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, sister Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti and friend-then-brother-in-law Jean Crotti.

The last rooms look to Duchamp’s artistic legacy through artists such as Andy Warhol, Sol Lewitt and Jasper Johns. While the impressive roster alone makes this a worthy show, it also distracts from the compelling premise that Duchamp’s obsession with his future legacy stems from his respect for people, culture and art, rather than self-involvement.

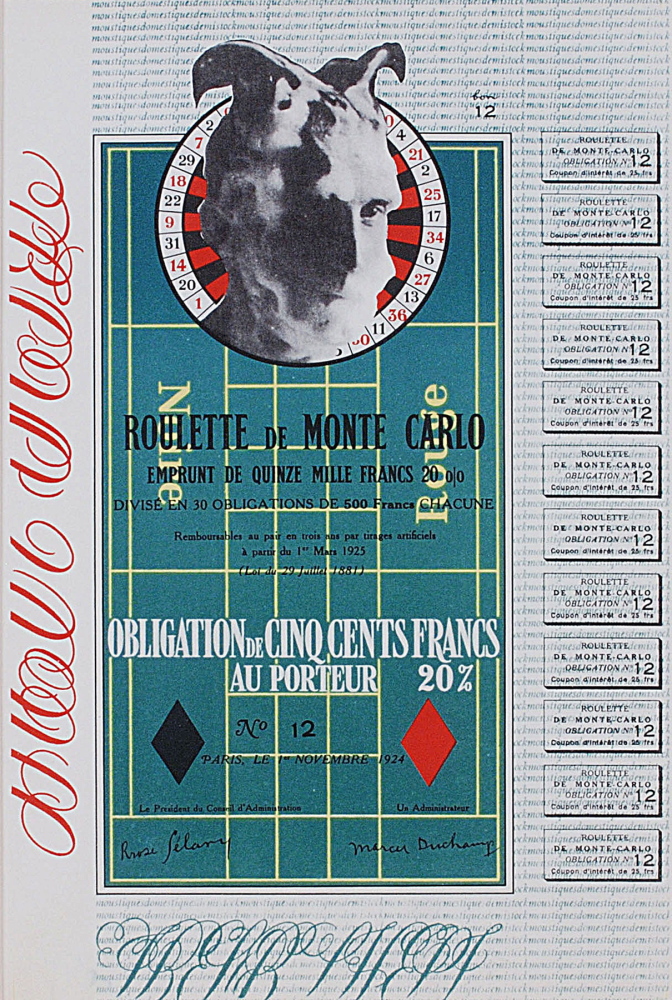

Duchamp’s “Boîte en-Valise” is a mini-museum with about 70 reproductions of the works he considered most important, including his “Nude,” “Fountain” (the infamous urinal signed “R. Mutt 1917” and Duchamp’s most important “readymade,” an art genre he invented), “The Large Glass,” “L.H.O.O.Q.” and “Tu m’.”

“L.H.O.O.Q.” appears in several formats in “Collaborations.” It is a reproduction of the Mona Lisa on which Duchamp drew a mustache and under which he wrote “L.H.O.O.Q.” which, when said aloud in French, means (among coarser alternatives) “her derriere is hot.” Because the work uses a reproduction, it is easily reproducible; and this leads us to consider the “art” here is the act, approaching vandalism, of defacing a reproduction, repeatable by anyone. One of the most exciting works in “Collaborations” is an exhibition invitation on which Duchamp attached a Mona Lisa playing card and wrote “L.H.O.O.Q.” Leaving off the mustache, Duchamp included the label “rasée,” which means “shaved,” referring to a thing that was never there but that we recognize. (This is the art equivalent of Maine-style driving directions like “take a right 5 miles before where Henderson’s store used to be.”) It is quite the sleight of hand.

Duchamp’s wit is indefatigable: “erasée” means “erased” and that missing “e” (and “e” means “painting” in Japanese – just sayin’) might have been erased, or not. And that is Duchampian wit: It never gives in, and it refuses to be final. Because you never really know if you “get” it, Duchampian wit can be frustrating. But, if you take the approach that Duchamp doesn’t want to be solved (well, at least not for another three or four years) but played with, then you get everything you need to know about Duchamp. If the work can’t be “solved,” you don’t need to get every joke. And how you experience Duchamp’s work comes down to this: Do you prefer endlessly insightful comedy or fruitless archeology?

Although he made many works after, “Tu m'” was Duchamp’s last painting on canvas. For us, however, the title matters: Literally, it’s the “you/me” portion of “you piss me off.” It cuts to the idea stated so well by Ansel Adams: “There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.” Change “photographer” to “artist” and you have opened the door to Duchamp. His work is not about the solitary artist expressing his genius through a heroic struggle with his materials. It’s about culture, language and how these are very playful and constructive (if sometimes misleading) components of who we are.

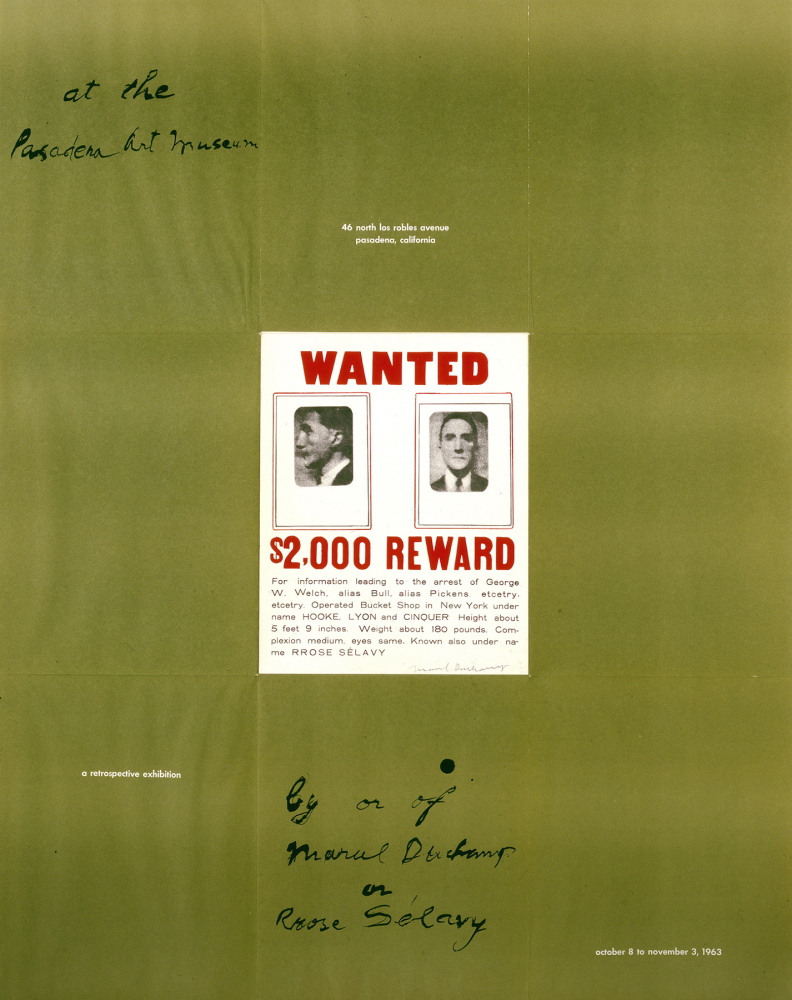

Next to this you/me author function problem is the conflict of Cubism so well illustrated by Rene Magritte who painted a picture of pipe under which he wrote “This is not a pipe.” (It’s not a pipe but a painting of a pipe.) The conflict of Cubism mirrors the difference between seeing a magic trick and having it explained to you – to explain it is to kill the magic. When Duchamp takes aliases and even portrays himself as a criminal, we feel his angst about having shared Cubism’s goal of exposing the mechanisms of art. (You can’t un-explain a magic trick, after all.)

From this standpoint, Duchamp makes sense. He loved art and was deeply conflicted about what he did to it. He laments how he helped Cubism push us out of paintings and into the one-way street of critical discourse. With play (in an anti-archeology kind of way), Duchamp hoped to reclaim, if not quite innocence, then maybe a freshness of sorts.

“Collaborations” is a reminder of the incredible academic resource the Colby, Bates and Bowdoin art museums are for the art audience of Maine. Bowdoin Museum of Art co-director Anne Goodyear was the force behind the show. Her book “aka Marcel Duchamp: Meditations on the Identities of an Artist” was published this year by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. (Goodyear was the editor and an essayist). While many Maine art venues are local in subject and source, our leading academic institutions stand below no one in what they have to say on the world stage.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. Contact him at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.