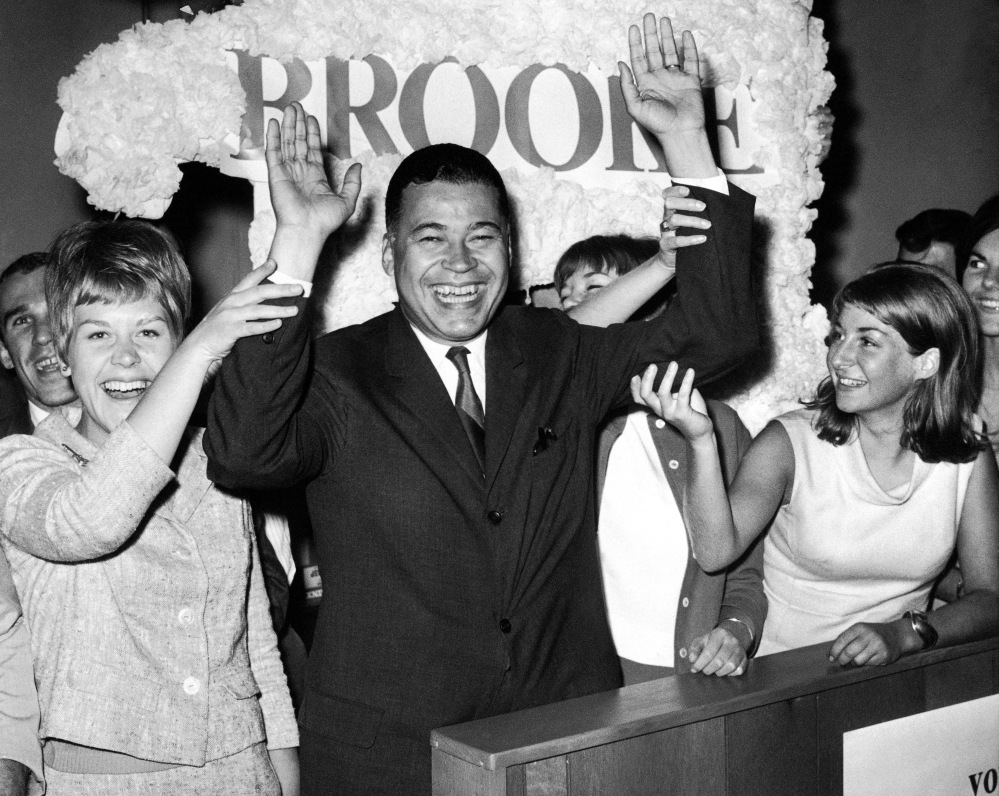

Edward W. Brooke, who in 1966 became the first African-American popularly elected to the U.S. Senate and who influenced major anti-poverty laws before his bright political career unraveled over allegations of financial impropriety regarding private loans, died his home in Naples, Fla. He was 95.

Ralph Neas, a family spokesman and former legislative aide to the senator, confirmed the death. The cause was not immediately disclosed.

Brooke, a liberal Massachusetts Republican, was one of only two African-Americans to serve in the Senate in the 20th century. He was the first to serve since Reconstruction, when state legislatures appointed senators. Six African-Americans have served in the Senate since Brooke left office in 1979.

Brooke grew up in a racially divided Washington and, after distinguished combat service in the segregated U.S. Army during World War II, he forged a legal and political career in Massachusetts. He became the state’s hard-charging attorney general before winning election to the Senate.

He was one of the most popular politicians in Massachusetts, known for his independence, both from civil rights leaders and from conservative members of his own party. Tall and husky, with a nimbus of closely cropped hair, he was regarded as charismatic and vigorous in a way that reminded many voters of another Massachusetts political figure: President John F. Kennedy.

In the Senate, Brooke served on the powerful Appropriations Committee and became the ranking Republican on the Banking Committee, which gave him influence over U.S. commerce, monetary and housing policy.

He was a black, protestant Republican representing a state that was more than 95 percent white, overwhelmingly Catholic and two-thirds Democratic. “I do not intend to be a national leader of the Negro people,” he told Time magazine after his Senate election. “I intend to do my job as a senator from Massachusetts.”

Because he represented an overwhelmingly white state, Brooke found it politically expedient to play down race and push for civil rights legislation discreetly, said Judson Jeffries, a professor of African-American studies at Ohio State University who has written extensively on blacks in politics.

Throughout his career, Brooke took a gingerly approach to the politics of race. He opposed two Nixon nominees for the U.S. Supreme Court over civil rights issues. He refused to join the Congressional Black Caucus, although he did speak at its annual convention. He voted in favor of busing as a means to desegregate schools, although many of his Boston constituents reviled the policy.

As state attorney general in the 1960s, Brooke showed the independence that marked his political career. He once fought the NAACP’s effort to boycott Boston’s public schools in protest of the city’s de facto segregation, ordering the students to attend class because the law required them to do so.

During the Watergate scandal, he was the first Senate Republican to call for President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Housing was his overarching passion. With Walter Mondale, D-Minn., he co-sponsored the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion or ethnicity.

Brooke hoped to influence civil rights through housing policy. “It’s not purely a Negro problem. It’s a social and economic problem – an American problem,” he told Time in 1967.

An amendment he introduced to the 1969 Housing Act capped public housing rent at 25 percent of income. In 1981, the cap was raised to 30 percent.

He later introduced and got passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which allowed women to obtain credit independent of their husbands.

“He was well respected on the Hill, because he was someone who could cross the aisle and work with people of a variety of perspectives,” said political scientist Darrell West, a former Brown University professor who works at the Brookings Institution.

In 2004, Brooke received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award, in large part because of his ability to bridge factions, West said.

Brooke culled friendships with segregationists including Sens. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., and John C. Stennis, D-Miss., who invited him to swim with them in the Senate’s pool. “They invited me to join them and urged me to use the pool as often as I could,” Brooke wrote in his memoir, “Bridging the Divide: My Life” (2006).

In political and media circles, Brooke was considered a potential presidential or vice presidential contender. But his career tumbled after he filed for divorce in 1976. He and his wife, the Italian-born Remigia Ferrari-Scacco, had been separated more than a decade, but she contested the divorce.

His deposition revealed that he had incorrectly reported to the Senate a loan from a friend and that he had helped his mother-in-law conceal money to help her qualify for Medicaid assistance for her nursing home care. He used some of the money to buy a Watergate condo.

Brooke said his deposition disclosure was a mistake, based on misunderstandings of his own finances. A 10-month Senate ethics investigation followed, and he was charged with welfare fraud.

The allegations cost him at the polls. He lost in 1978 to then-Rep. Paul Tsongas, D-Mass., who made a primary run for president in 1992.

The charges were later dropped, because the district attorney said the misstatements had no outcome on the divorce. The Senate ethics panel in 1979 said the offenses were not serious enough to warrant any punishment, and because he was no longer in the Senate, the committee’s role was moot.

The youngest of three children, Edward William Brooke III was born Oct. 26, 1919, in Washington. His father was a Veterans Administration lawyer.

The future senator graduated from Dunbar High School in Washington. He entered Howard University and became president of the university’s chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, the nation’s oldest black collegiate fraternity. He pursued pre-medical studies until he failed organic chemistry and concluded he wanted to become a doctor only because of the prestige it offered. He changed his major to sociology and received his bachelor’s degree in 1941.

During World War II, Brooke served in the all-black 366th Infantry Regiment in Italy. He was awarded a Bronze Star for leading a daylight attack on an artillery bunker. After the war, still stationed in Italy, he met Ferrari-Scacco, the daughter of a Genoese paper merchant. They married in 1947.

After the war, he moved to Boston after two Army friends convinced him it was a city friendlier than Washington toward African-Americans. He entered Boston University law school on the GI bill and edited the university’s law review. He graduated in 1948, then opened a law firm in Roxbury, a burgeoning black community in Boston.

Two friends prodded Brooke to run for the state House of Representatives in 1950. Since election would be difficult, he ran in both the Republican and Democratic primaries, a strategy known as cross-filing that was legal at the time.

He received the Republican nomination, but lost the general election. At the time, the Republican party had a strong liberal wing, especially in the Northeast. He ran again in 1952, but slurs against his interracial marriage were so brutal, he renounced politics and focused on his law practice.

In 1960, Brooke ran for Massachusetts secretary of state. He lost the election but was appointed to the Boston Finance Commission, a watchdog group, where he earned a reputation for rooting out corruption. In 1962, he won election as state attorney general by combining moderate politics with adroit campaigning skills and became the first African-American to hold that post in any state.

He served two terms and vigorously prosecuted corrupt politicians and organized crime and obtained more than 100 grand-jury indictments.

After his 1978 Senate defeat, Brooke became chairman of the National Low Income Housing Coalition and practiced law and later sat on several corporate boards. In 2008, journalist Barbara Walters admitted maintaining a long-running affair with him during the course of his first marriage.

Survivors include his wife of 35 years, Anne Fleming Brooke of Coral Gables, Florida; two daughters from his first marriage, Remi Goldstone and Edwina Petit; a son from his second marriage, Edward W. Brooke IV; a stepdaughter, Melanie Laflamme; and four grandchildren.

In 2002, Brooke was diagnosed with breast cancer, a rare disease in men, and underwent surgery to remove both breasts.

Brooke was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’s highest civilian honor in 2009, for his contribution to fair housing laws and for his inspiration to later generations of African-American officeholders.

“If one looks at civil rights broadly, I would not call him a civil rights icon,” Jeffries said, “but I would call him a pioneer of the civil rights movement.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.