Maine Wild Blueberry Crisp and Ripe Mango Sorbetto have been longstanding favorites at the Gelato Fiasco store in Brunswick, where the gelato maker has been serving its frozen treats for seven years. But in 2014, the business took on an international flavor.

Josh Davis, co-founder and CEO of Gelato Fiasco, traveled in June to the Chinese cities of Shanghai and Ningbo to meet with companies eager to buy his product, made with milk from Maine dairy farms. Now he’s filing the paperwork to export his gelato to Hong Kong, mainland China and South Korea.

“Even people not familiar with every detail of Maine get a good feeling about food products that come from Maine,” he said.

That observation is apparently widespread as seafood and agricultural commodities are driving much of the growth of Maine’s exports. International sales of Maine food products more than doubled between 2007 and 2013, according to federal trade data.

The rise in food exports coincides with the growth of domestic sales in those categories and the rise of the middle class in emerging markets, particularly China, where more people can now afford premium food products from the United States. According to data collected from trade forms that companies fill out for the U.S. Commerce Department, total exports in seafood, agricultural commodities and prepared food products increased from $276 million in 2007, the last year before the Great Recession, to $557 million in 2013.

Canada, by far Maine’s largest trade partner, is the leading importer of those products. In 2013, Canada imported about $300 million worth of Maine food and agriculture products, some of which – lobster and potatoes – were processed and exported back to buyers in the United States.

But after Canada, the next four leading importers in 2013 were all in Asia – Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea and China.

Hong Kong, a former British colony that is a special administrative region within China, is on track this year to overtake Japan and move into second place, with imports of $20.5 million through September.

China is catching up and is on track to overtake both South Korea and Japan. Exports to China increased more than 1,000 percent between 2007 and 2013, from $1.4 million to nearly $17 million. By September 2014, exports to China had already exceeded $17 million.

The rising popularity of Maine-made foodstuffs is a boon to multiple industries.

Jasper Wyman & Son, a Milbridge-based company that employs 170 Mainers, is one of the largest producers of frozen blueberries in the United States. President Ed Flanagan says expanding exports give his company diversity, so if sales in one country fall because of internal factors, such as a recession or currency devaluation, those losses can be offset when sales pick up in another country.

Declining blueberry consumption in economically troubled Japan has been offset by rising sales to China, he said. About 15 percent of the company’s sales are exports, and shipments to Asia account for most of the export growth.

“The Asia markets, as they have prospered, have become enthusiastic about blueberries,” he said.

The trade category that includes cranberries and blueberries increased 127 percent between 2007 and 2013, from $10 million to $23 million. Exports of frozen blueberries doubled over the same period, from $10 million to $20 million.

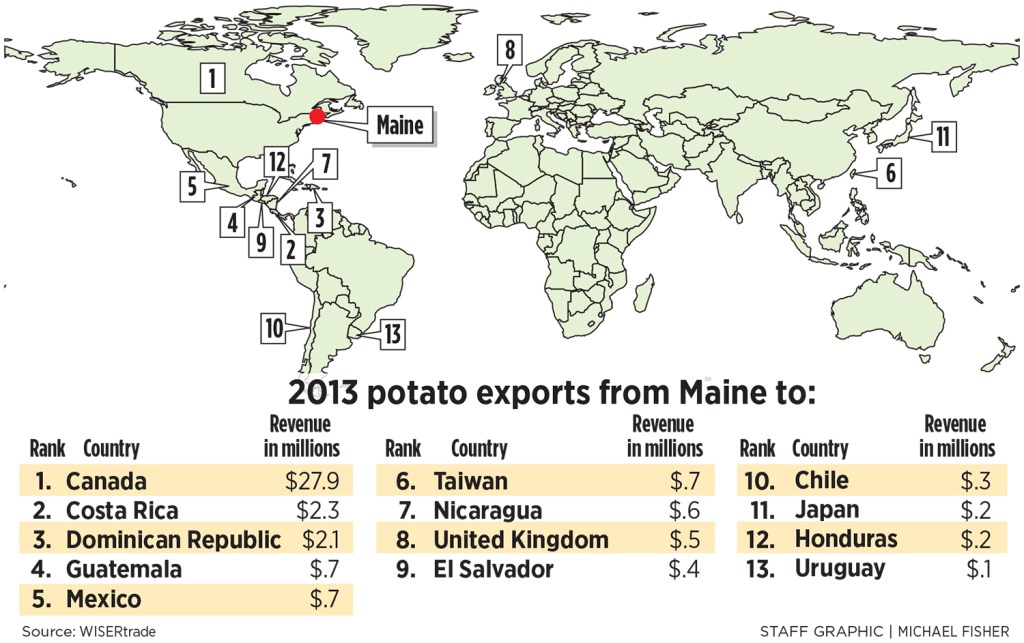

Potatoes, too, have been enjoying a boon of worldwide popularity. Sales of frozen Maine potatoes increased nearly 200 percent, from $9 million to $27 million from 2007 to 2013.

Potatoes are an established product that can be grown in most parts of the world, so increased sales come from being more competitive in price and quality rather than introducing a product to a new market, said Donald Flannery, executive director of the Maine Potato Board.

Maine’s farmers and food processors are also benefiting from a trend in which families in other nations are adopting the American habits of eating out in restaurants more often and eating more prepared foods at home, said Gordon Pow, senior vice president at Penobscot McCrum, which grows potatoes on 5,000 acres in Aroostook County and operates a processing facility in Belfast. The company is a major supplier of potato skins, potato wedges and twice-baked potatoes.

The family-owned company, which employs 250 people, exports between 10 percent and 12 percent of its total sales, and most of its exports go to restaurants in Europe and Russia, he said.

Seafood also represents a big chunk of Maine’s export growth. Live lobster exports between 2007 and 2013 increased 67 percent, from $145 million to $242 million, with exports to Asia driving much of that growth.

Elvers, which sold for prices topping out at $1,800 a pound in 2011 and 2012, saw exports increase from just over $1 million to $14.6 million from 2007 to 2013. The baby eels are sold to buyers in South Korea and Hong Kong.

AN IMPRECISE SCIENCE

Overall, Maine’s exports are up, but the increase is at a slower pace than what the nation is experiencing as a whole.

Maine exports are difficult to calculate, though. The federal trade numbers show that Maine exported $2.7 billion worth of products in 2013, a number indicating Maine’s exports have not grown at all since 2007. However, the official numbers are not reliable because of flaws in the federal data, especially with regard to computer chips.

Recent federal data exclude computer chips manufactured at the former National Semiconductor plant in South Portland. After Texas Instruments Inc. purchased National Semiconductor in 2011, it stopped listing Maine as the “point of origin” of its Maine-made computer chips. The chips for years had been among the leading exports from Maine. Exports in the trade category that included computer chips fell from $919 million in 2011 to $95 million in 2013.

Another problem in the federal data: a category called “Petroleum Gases and Other Gaseous Hydrocarbons,” which in 2013 accounted for exports valued at $135 million. Officials at the Maine International Trade Center, the quasi-state agency charged with helping Maine businesses increase exports, believe the category reflects a lone Washington County company near the Canadian border that transports natural gas. The fuel comes into Maine from New Brunswick via a pipeline and is trucked by the company to customers on both sides of the border – not really a commodity produced in Maine and exported.

When those two categories are eliminated in both the Maine and U.S. data, Maine’s exports grew from just under $2 billion in 2007 to $2.5 billion in 2013, an increase of about 25 percent. During that same time period, U.S. exports increased by 39 percent.

Maine lags behind the nation because exports are driven by multinational corporations, and Maine is primarily home to small and medium-sized companies, said Janine Bisaillon-Cary, president and state director of the Maine International Trade Center.

Products and commodities with the largest growth nationally are oil, computers, vehicles and aircraft, soybeans and grain. Although Maine has some manufacturers involved in the supply chain, it’s not at the same level as in states with large manufacturers, such as California, Texas and Ohio.

The growth of Maine’s exports in food and natural resources shows that Maine is competitive globally in those areas, and businesses and policymakers should work to develop those markets more, said Bisaillon-Cary.

“You focus on where the growth is,” she said.

PAPER PRODUCT EXPORTS GROW

Maine’s dominant manufacturing sector, the paper industry, is also heavily dependent on natural resources. That sector is also showing growth in exports.

Paper and paperboard exports increased 82 percent between 2007 and 2013, from $96 million to $175 million. Coated paper and coated paperboard increased from $3 million to $47 million.

That growth occurred even as the industry has been shedding jobs and closing plants in Maine. Overall paper production has remained steady because the remaining mills have increased capacity. Also, while the paper market historically has been a domestic one, the relatively small overseas market is growing, said John Williams, president of the Maine Pulp and Paper Association.

“We make high-quality paper, and there are markets overseas that are sure interested in that paper,” he said.

Regardless of what his exporting peers are doing, Gelato Fiasco’s Davis sees a world of possibilities for his products. The company began exporting gelato to Barbados and the Bahamas in 2013 and now, in addition to new Asian markets, is preparing to enter another: the Middle East.

“What makes us proud is that we are bringing pieces of Maine to places that are very far from Maine,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.