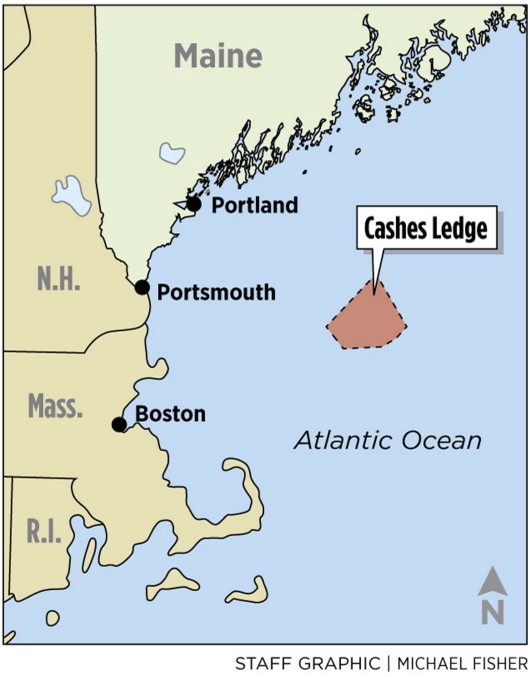

Roughly 100 miles off the coast of southern Maine, a hidden, mountainside forest that scientists describe as an ecological time machine offers glimpses of an abundance long lost on the New England coastline.

Schools of oversized cod and pollock congregate in Cashes Ledge, drawn to the food and shelter found in one of the largest, densest kelp forests in the world. Endangered North Atlantic right whales, humpback whales and various species of shark swim above, while sponges, sea stars and sea anemones form a brightly colored blanket on the bottom – all in an area largely off-limits to commercial fishermen.

Now a proposal to reopen part of the 500-square-mile area to groundfishing is reviving debate about how to balance conservation with attempts to keep New England’s historic groundfishing industry from becoming extinct. That debate will continue Tuesday and Wednesday as the New England Fishery Management Council holds public hearings in Brewer and Portland on the Cashes Ledge proposal and other potential changes to regional fishing regulations.

“It makes no sense whatsoever to allow the (gains) we have established over the past few years to be destroyed for a few boats,” said Greg Cunningham of the Conservation Law Foundation, a nonprofit that pressured regulators to create the refuge for cod and other struggling groundfish species in 2002. “The fish they are targeting there are readily available in other areas.”

Fishermen and members of the management council – the regional federal commission that regulates the industry – insist that the proposed changes still will protect the rare Cashes Ledge habitat while giving fishermen access to surrounding waters. The council is accepting public comment on the suite of proposed changes through Thursday.

“We are not opening up Cashes Ledge or Ammen Rock if this goes through,” Harpswell fisherman and council member Terry Alexander said in referring to the tallest peak of the cluster of submerged mountains. “All we are opening up is the deep water to the west of Cashes Ledge.”

Under the “preferred option” being considered by the council, the more than 500-square-mile closure zone would shrink by roughly 70 percent. All mobile “bottom-tending” fishing gear – such as draggers and trawlers that can disturb the sea floor – would remain banned around Ammen Rock and most of the ledge proper. But fishermen could resume targeting haddock, cod, pollock and other groundfish in surrounding mudflats that the council deemed “less vulnerable to accumulating adverse effects.”

The potential changes come at a critical juncture for New England’s groundfishing fleet.

As many as 350 Maine-based vessels plied the waters for groundfish in 1990; today that number is less than 50. And the $7.6 million in groundfish landed in Maine in 2013 represented roughly 2 percent of the $378.7 million in lobster that was landed that year, and 1.3 percent of the total value of the commercial fisheries harvest in the state that year.

Responding to surveys showing record-low cod populations, the fishery council cut the region’s cod quota by 75 percent in November on top of already severe reductions. The cuts all but eliminated cod fishing in the region this year, although boats can continue to target haddock, pollock and other groundfish with stable populations.

Conservationists and researchers are raising alarms about proposed changes they insist could affect a unique “biodiversity hot spot” in the gulf.

Cashes Ledge is an outcropping of bedrock about 80 miles due east of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that at its tallest point, Ammen Rock, sits roughly 40 feet below water. Most of the Gulf of Maine is deep, dark and cold, so areas where geologic formations rise closer to the surface – in places such as Cashes Ledge, Jeffreys Ledge and Stellwagen Bank – tend to have higher concentrations of sea life. At Cashes Ledge, cold but nutrient-rich water circulating in the depths of the gulf hit the rock outcropping and rise high enough in the water column to allow photosynthesis, leading to a proliferation of life of all sizes.

“The combination of sunlight and nutrient-rich waters fuels the growth of these (fish and invertebrate) larvae, creating a productive area that supports one of the largest kelp forests and deepest seaweed communities in the world, as well as abundant populations of large predatory fish including cod, pollock, wolf fish and sharks,” the fishery council states in its description of the ledge. “These unique conditions are found nowhere else in the greater Gulf of Maine/Georges Bank ecosystem, clearly making the Cashes Ledge area a rare habitat type.”

“It really is a remarkable place,” said Bob Steneck, a researcher and professor at the University of Maine School of Marine Sciences who traveled to Cashes Ledge annually in the 1980s and 1990s.

Between the powerful currents and the cold conditions, Steneck said, Cashes Ledge is among the more challenging places around the globe where he has scuba dived to conduct research. Steneck said he was struck by the abundance of large predatory fish, such as cod and haddock, as well as the fact that the ledge provided habitat to almost every life stage of the fish, from spawning adults to “young of the year.” But Steneck said he witnessed a significant decline in abundance during that time because fishermen began targeting the area.

Steneck described Cashes Ledge as an example of “an ecosystem past” that is largely gone from New England after centuries of commercial fishing. He was among more than 130 researchers from around the world who signed a letter sent to the fishery council last year expressing concerns about “opening closed areas to relieve short-term fish shortages at the expense of future ecosystem recovery.”

“These local stocks are very fragile and I think we have extirpated most of them along the Gulf of Maine,” Steneck said.

Alexander, the Harpswell fisherman who is one of 17 voting members on the council, said Gulf of Maine groundfish stocks already are protected by the strict annual catch limits. He said continuing the current closure is not a viable option in his eyes and would be unlikely to pass muster with the majority of the rest of the council. Reopening the deep-water areas near the ledge could help the few remaining groundfishing vessels still in business to reduce costs, he said.

“We need to be able to reach our quota and catch it fast in order to reduce expenses,” Alexander said.

But Cunningham, at the Conservation Law Foundation’s Maine office, countered that the council’s own data support leaving the current closure intact. The “no action” option was ranked as having the most positive effects on habitat, as well as short-term and long-term economics, among the six scenarios examined by the council.

“There is no reason to compromise,” Cunningham said. “There is not a good argument other than to appease a couple of fishermen. The science – both the ecological and economic science – both say to leave this place alone.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.