Like a lot of other Maine writers who hold the coming-of-age novel “To Kill a Mockingbird” close to heart, Gibson Fay-LeBlanc was skeptical but curious when he heard that a publisher plans to release a sequel more than a half-century after the publication of Harper Lee’s literary classic.

“I am interested but a little wary,” Fay-LeBlanc said. “Why did it take so long? Where has it been? What I am really hoping is that it is good. It doesn’t need to be as good as ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ but I hope it’s good. I don’t want the drama broken.”

Lee wrote her sequel, “Go Set a Watchman,” before she wrote “To Kill a Mockingbird.” It is set 20 years after the original book, and features many of the same characters. Its existence has been long rumored, and many scholars speculate that it served as a draft for “To Kill a Mockingbird,” which won a Pulitzer Prize and remains required reading for millions of American school kids. An estimated 40 million copies have been sold.

The publisher, HarperCollins, will release “Go Set a Watchman” in July. It promises to be one of the most anticipated books of the year if not generations. Already, pre-orders have put the sequel at the top of Amazon’s best-seller list.

It also has become a controversial book. Many fans worry that Lee, who is 88 and in poor health, was pressured to offer a book that she and her representatives have long declined to publish. Those fears were reinforced by the timing of the news, which came a month after Lee’s older sister died. The sister, an attorney, shielded Lee from unwanted publicity after “To Kill a Mockingbird” became part of the country’s cultural lexicon, and oversaw the writer’s estate and legal affairs.

‘I HAVE TO EXPERIENCE’ THE BOOK

“To Kill a Mockingbird” is considered one the most influential books in literary history. Published in 1960 and never out of print, it tells of a young girl named Scout and her hero father, the lawyer Atticus Finch, who stands for moral principle in his defense of a black man accused of raping a white woman.

Lee, who is from Alabama, set her story in the fictional Southern town of Maycomb in the early 1930s. It presages America’s difficult struggle with civil rights.

Fay-LeBlanc, a writer and educator, read the book in eighth grade and has used it in his middle and high school classes.

“It’s such an amazing coming-of-age story, this young person who is realizing things about the world and grappling with injustice and being forced to confront that and her own faulty assumptions about people,” he said.

Fay-LeBlanc said his feelings about the sequel to “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the next “Star Wars” movie are similar.

“Whether it’s good or not, I have to experience it,” he said. “And I know publishing well enough to know that it’s entirely possible that it’s really good. It may just be that her editor didn’t like it or didn’t think it was as worthy as the other one.”

INTEREST IN REVISITING CHARACTERS

Every eighth-grade student at Waynflete School in Portland reads “To Kill a Mockingbird,” said English teacher Laura Lennig. The book is required reading because it says a lot about America – then and now, Lennig said.

“It’s a combination of a work with these really wonderful, compelling scenes of friendship and forgiveness, justice and injustice and family, coupled with this amazing young voice taking us through the story,” she said. “Here’s a book set in the 1930s, written in the 1960s and everything inside it is totally relevant for us to today, for better or worse.”

She understands the interest in a sequel. It will give readers a chance to drop in on the characters again, at a different stage of their lives.

“We’re all interested in how Scout is as an adult and how things are in Maycomb now. It’s revisiting a familiar place,” Lennig said.

BIG IMPACT FOR MAINE PHOTOGRAPHER

When the National Endowment for the Arts began the Big Read to encourage community reading, among the first books in the program was “To Kill a Mockingbird,” recalled Felicia Knight of Scarborough. She was communications director for the NEA at the time.

Knight has read the book multiple times, and looks forward to “reading what is almost another treatment of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ maybe a first draft or rough draft. It will give me more insight into this book that I love.”

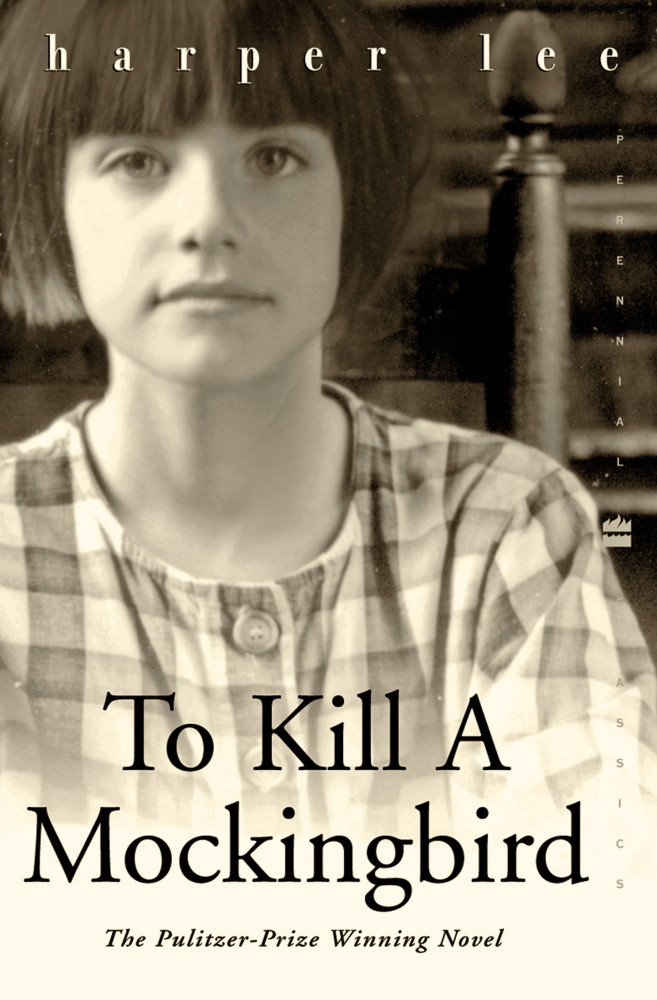

Freeport photographer Jack Montgomery has a different connection to the book. He shot the cover photo for a 2001 Random House paperback version of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” A friend suggested Montgomery to the photo acquisitions editor at Random House.

Montgomery shot a local girl in bib overalls and in an old-fashioned dress. After at first rejecting Montgomery’s work, Lee eventually chose a composite of both shots for the cover – an image of Montgomery’s Scout wearing a simple country dress, seated in a Shaker-style chair. He didn’t have direct contact with Lee and corresponded through editors at the publishing house.

The shot helped Montgomery establish his career in photography. “It gave me instant credibility,” Montgomery said. “It’s been reproduced so many times.”

Montgomery has a long history with “To Kill a Mockingbird.” A lawyer himself, he’s always identified with Atticus Finch, and held up his own legal work in light of Finch’s moral character. “He was always an archetypal figure for me. He set the standards,” Montgomery said.

RELEASE OF SEQUEL QUESTIONED

Gary Lawless, who operates Gulf of Maine Books in Brunswick, said customers are already asking for “Go Set a Watchman.”

“People are very curious about it, and so am I,” he said.

Lawless read “To Kill a Mockingbird” in the 1960s, when he was in high school in Belfast on Maine’s midcoast. His father was the police chief in town, so Lawless had a perspective of justice. “To Kill a Mockingbird” expanded that view.

“I was really interested in how justice worked, but I didn’t know much about justice outside my own state,” Lawless said. “I really didn’t know about the South and people of other skin color. … But we had a really good teacher, and we all felt this was something that was basically wrong. It taught us an injustice is happening.”

Yarmouth writer Lily King is curious to see how Lee evolved her characters and story. Those curiosities aside, King said the circumstances of the new book “feel a little fishy.”

Lee has been adamant in her refusal to publish the book and shunned nearly all publicity associated with “To Kill a Mockingbird” for 55 years. The sudden decision to publish the sequel after her sister-lawyer’s death “raises serious questions about the motives and desires of everyone involved,” King said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.