LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — On a hot Friday last July, a parolee was mowing a lawn in a small cul-de-sac on the west side of the city when he stopped to ask for a glass of water.

The 70-year-old widow whose yard he was mowing told him to wait on her porch. Instead, she said, he jerked the storm door open, slammed her against the wall, forced her into the bedroom and raped her. The parolee pushed her with such force, she said, that her front teeth were knocked loose.

Then he went back to mowing the lawn.

Milton Thomas, 58, said he’s not guilty. His trial is set for March.

Thomas has been in and out of Arkansas prisons since 2008 for nonviolent crimes, including check fraud. After he got out in November 2013, the state predicted he was a low risk to commit another crime, Thomas said, and assigned him the least amount of supervision.

His low-risk prediction would have been calculated based on answers to a lengthy questionnaire, the latest tool among the nation’s court systems to try to predict the likelihood that an offender will commit a crime again.

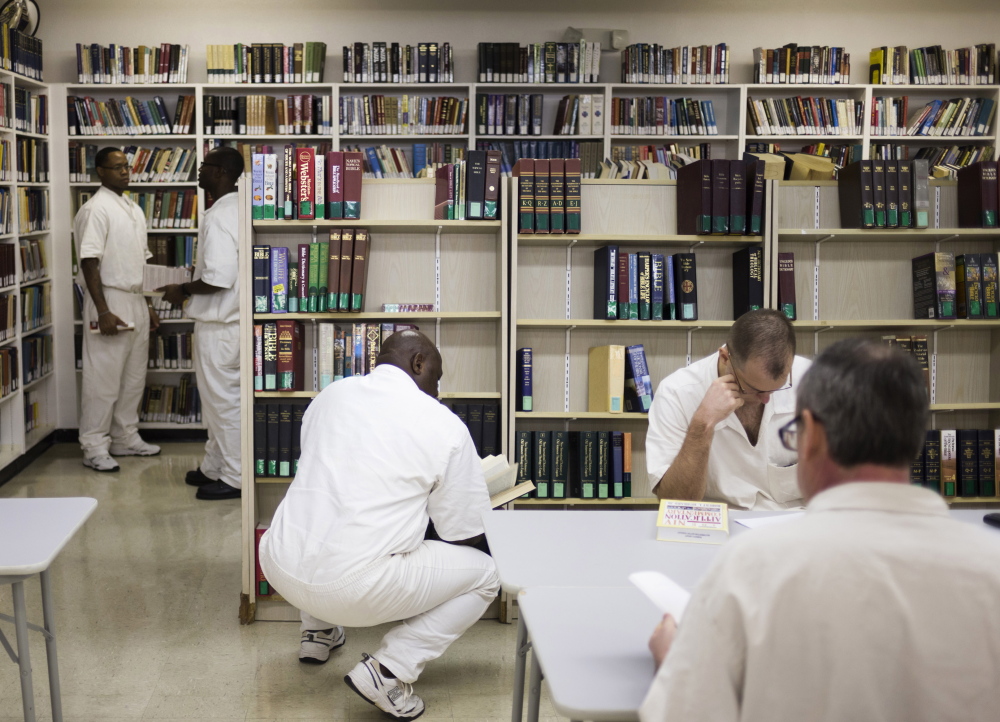

Across the country, states have turned to a data-driven movement to drive down prison populations, reduce recidivism and save billions of dollars. One emerging practice is the use of risk-and-needs assessment tools, which are questionnaires that explore issues beyond criminal history. They are based on surveys of offenders making their way through the justice system.

In a country with the highest incarceration numbers in the world, these questionnaires are a pillar of a new effort to get people out of prison. Repeat offenders are a major driver of bloated prison populations. But an Associated Press examination found significant problems with the surveys, which are used inconsistently across the United States, sometimes within the same jurisdiction.

SURVEYS COME WITH OWN RISKS

Supporters cite some research, such as a 1987 Rand Corp. study that said the surveys can be up to 70 percent accurate in predicting the likelihood of repeat offenses, if they are used correctly. Even the Rand study, one of the seminal pieces of research on the subject, was skeptical of the surveys’ effectiveness.

It’s nearly impossible to measure the surveys’ impact on recidivism because they are only part of broader efforts.

These assessment surveys, used for crimes ranging from petty thievery to serial murders, come with their own set of risks.

Many rely on criminals to tell the truth, though jurisdictions do not always check to make sure the answers are accurate.

The surveys are clouded in secrecy. Some states never release the evaluations, shielding government officials from being held accountable for decisions that affect public safety.

Some have the potential to punish people for being poor or uneducated by attaching a lower risk to those with steady work and high levels of education.

The surveys can include more than 100 questions and explore a defendant’s education, family, income, job status, history of moving, parents’ arrest history, or whether he or she has a phone. A score is affixed to each answer and the result helps shape how the defendant will be supervised in the system.

“How easy would you say it is to acquire drugs in your neighborhood?” a convicted thief could be asked.

“How many prior sex offense arrests (with force) as an adult?” a sex offender could be asked. A bubbled answer sheet lists options ranging from zero to more than three.

The idea is to use data about past offenders to predict what current defendants with similar backgrounds might do when released from prison. A major push is to free up parole and probation officers to focus on those more likely to reoffend, instead of lower risk inmates.

“It is a vast improvement over the decision-making process of 20, 30 years ago when parole boards and the courts didn’t have any statistical information to base their decisions on,” said Adam Gelb, director of the Public Safety Performance Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts, which is working with the U.S. Justice Department on changes to the prison systems nationally.

Cost savings are significant. In Arkansas, a prisoner costs the state $63 a day. A parolee costs $2. But the sexual assault case in Little Rock ALSO points to shortcomings.

Before Thomas was released, the parole board assessed him as a high risk to commit more crimes. But a second risk assessment, conducted by the state’s community supervision agency, found him to be a low risk, Thomas told the AP. Thomas said he has no recollection of answering questions from the lengthy survey.

Not only were Thomas’s contradictory assessments never explained, but after he was arrested on charges of raping Diana Miller, he was assessed again. The AP doesn’t identify victims of sexual assault, but Miller, now 71, agreed to be identified by her middle and married names because she said it is important for her story to be told.

Stunningly, Thomas’ risk-rating decreased after the rape charge.

The reason for the difference? The state couldn’t figure out how old Thomas was when first arrested, according to Solomon Graves, a member of the state parole board.

In June 2013, Thomas said he wasn’t yet 25 when first arrested, a high-risk factor, Graves said. The following year, Arkansas criminal history reports listed Thomas as having been in his late 30s when first arrested, so Thomas’s risk-rating was lowered. In a letter to the AP, Thomas said he was 19 when he was first arrested.

BEWILDERING CALCULATIONS

The calculations for determining probation conditions are often just as bewildering.

In February 2014, an Arkansas consultant said a majority of male parolees and probationers were classified as low risk by the state’s Department of Community Correction but 46 percent were rearrested within 18 months – “creating a potentially dangerous situation for public safety,” consultant JFA Associates LLC concluded.

“Virtually any recidivism reduction plan can be helpful,” said U.S. Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., who favors changes in prison policies.

Scott co-sponsored legislation in the last Congress that called for using risk assessment surveys for the federal prison population. “I think you ought to have some assessment and do the best you can and keep updating it based on the research. But you ought not be afraid of a system that’s working on average because of one anecdote.”

DOZENS OF DIFFERENT SURVEYS

Jurisdictions use dozens of different surveys that vary in the kinds of questions asked and how they are used. The Justice Department is helping bankroll this movement by providing millions of dollars to help states develop and roll out changes.

The goal is ultimately to save money, since states and counties spend some $92 billion a year on corrections.

But in most cases, the surveys can only work if the rest of the judicial system is working properly.

In September, that gap played out in a juvenile courtroom in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

There, a teenager faced sentencing for a charge of aggravated battery with bodily harm stemming from an incident one year earlier over a neighbor’s dog. The neighbor let his dog out without a leash, and the barking dog ran toward the teen’s father. The teen’s dad told the dog to go away, upsetting the dog’s owner. Curses and threats followed. The dog owner walked away, then turned back toward the teen’s dad and took his shirt off. When the teen’s father called the police, his son joined the fracas and stabbed the dog owner, police said.

The teen was given a 128-item questionnaire called the Positive Achievement Change Tool, or PACT, standard for juvenile cases in Florida. He was deemed a low risk to commit further crimes. The AP does not generally name juveniles charged with crimes.

The survey asked about his history of school expulsions, views on the value of education, whether his parents had been arrested and whether his friends had committed crimes.

One answer helping earn him the low score: getting credit for having a good group of friends.

But when the prosecutor, Maria Schneider, dug into the defendant’s background, she found that his circle of “friends” had attempted a drive-by shooting of his house because they said he owed them money.

‘COMPLETELY FLAWED’

The assessment “is completely flawed,” Schneider said in court. “They were obviously depending just on the information this young man was providing himself,” she said.

Corrections systems always have been plagued by inaccurate information, said Sean Hosman, founder of Assessments.com, the company that, in collaboration with Florida, fashioned the survey.

Even so, he said, the assessments are an improvement over past practices and help defendants get a fair shot.

“Too often,” Hosman said, “we would do a gut check or you’d use intuition … or assess them based on the color of their skin, or the fact that we knew their brother and they went through here before.”

The surveys have been largely confined to parole and probation decisions, but they increasingly are being used for sentencing.

One 2013 study said at least one court system in 20 states is using these questionnaires at some stage of sentencing.

Sonja B. Starr, a University of Michigan law professor who wrote the 2013 study, said the surveys could punish people for being poor.

“They are about the defendant’s family, the defendant’s demographics, about socio-economic factors the defendant presumably would change if he could: Employment, stability, poverty,” Starr said. “It’s basically an explicit embrace of the state saying we should sentence people differently based on poverty.”

The Justice Department’s posi- tion on the tools has been inconsistent. On one hand, it’s funding them, and on the other, the department is putting on the brakes.

“Criminal sentences must be based on the facts, the law, the actual crimes committed, the circumstances surrounding each individual case, and the defendant’s history of criminal conduct,” U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder told the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers in August. “They should not be based on unchangeable factors that a person cannot control, or on the possibility of a future crime that has not taken place.”

The Justice Department cautioned the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which sets national policies, about relying too much on the new surveys. But jurisdictions are sorely tempted to test new systems that could save billions.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.