Sea levels off Portland rose by 5 inches during 2009 and 2010 as part of what researchers called an “unprecedented” two-year spike resulting from changes in ocean circulation that are tied to rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere.

They said extreme fluctuations in sea level are likely to occur more frequently, given the rate of climate change, which raises the threat of more frequent flooding, erosion and damage to homes and property along the coast.

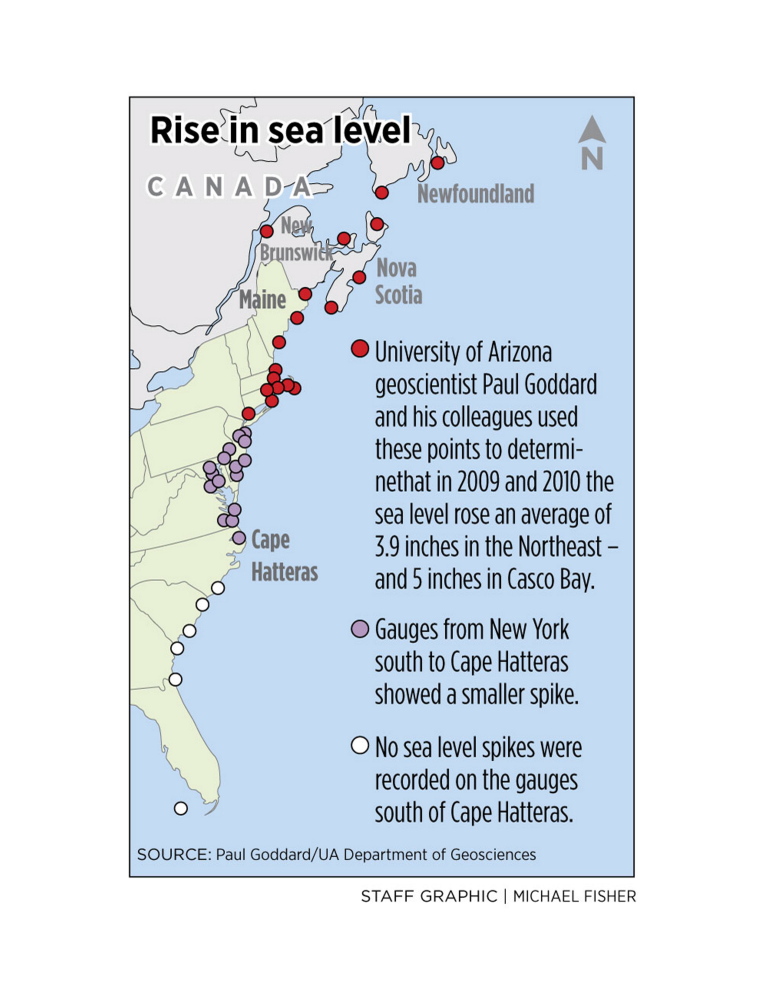

Scientists at the University of Arizona, with help from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, used monthly tidal data, some dating to the 1920s, to track sea levels at tide gauges along the Eastern Seaboard from Key West, Florida, to Newfoundland, Canada. The results of their study were published this week in the periodical Nature Communications.

Sea levels increased by an average of 3.9 inches in the Northeast – the tide data were gathered at 18 locations from New York to Newfoundland – but rose by 5 inches in the waters of Casco Bay, according to the study.

“This magnitude of interannual SLR (sea level rise) is unprecedented (1-in-850 year event) during the entire history of the tide gauge records,” the study says.

The biggest increases occurred between April 2009 and March 2010.

Tide data collected in the mid-Atlantic and Southeast ocean waters in 2009 and 2010 showed rises as well, but not extreme increases.

George MacDonald, director of sustainability for the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, hadn’t seen the study but cautioned that highlighting a two-year period can sometimes produce skewed results. He said 20- or 30-year studies often give a better picture.

Historically, sea levels regularly rise and fall at unpredictable rates, but the readings reported in the study reflect a peak period of increase, the authors said.

The University of Arizona researchers said such extreme events are likely to occur with greater frequency as the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases.

“In terms of beach erosion, the impact of the 2009-2010 (sea level rise) event is almost as significant as some hurricane events,” the authors wrote, noting it caused flooding along the Northeast coast independent of hurricanes and winter storms.

DECADES OF TIDE RECORDS REVIEWED

The sharp sea level rise in 2009-10 was attributed to changes in ocean circulation tied to rising levels of carbon dioxide, which traps heat in the atmosphere. As water gets warmer it expands, and last year NOAA scientists reported that the Gulf of Maine is warming at a rate faster than 99 percent of the world’s ocean water.

The higher level puts Portland and surrounding areas at a greater risk for flooding, which could be exacerbated by extreme weather.

Paul Goddard, a doctoral candidate at the University of Arizona, and a team of researchers reviewed monthly tide records at 40 points along the East Coast going back to the 1920s and found that no other two-year period had such a big increase.

“The sea level rise of 2009-2010 sticks out like a sore thumb for the Northeast,” Goddard said in a written statement.

Sean Birkel, research assistant professor at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute, said the rise didn’t surprise him, but he also said it’s not quite as alarming as it seems.

“It’s definitely a significant rise during a short interval, but our research has shown a lot of variability, or ups and downs, and that 2009-10 is likely a peak,” he said. “But the overall trend is certainly that seas are rising. No one disputes that.”

MAINE LOOKS AHEAD AT COASTAL LAND USE

Jianjun Yin, an assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Arizona, said the current rate of increase in greenhouse gas emissions suggests that rising sea levels, and corresponding coastal flooding, are likely to occur more often in the Northeast over the next several decades.

Rising sea levels and the side effects are increasingly on policymakers’ radars in Maine.

Next week, the Legislature’s State and Local Government Committee will host a public hearing on a bill, L.D. 408, that would require all future comprehensive land use plans in coastal communities to consider sea level rise when managing growth.

Dylan Voorhees, global warming project director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine, said sea level rise is an impact of climate change that has consistently turned out to be worse than the predictions.

“The more we learn about warming temperatures, glaciers and extreme storms, the more stark (the) unmitigated climate change becomes for coastal communities,” he said. “On the positive side, we’re pleased that more and more Maine people and communities are taking these coastal climate impacts seriously and are restarting conversations about what to do about it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.