After she makes 16 beds at the hotel where she works, Lori Godin boards a bus, waits in line at a Portland homeless shelter, and if she’s lucky, she will get to make one more.

Standing in the cold, Godin adjusted the straps of her backpack, the one that she’s lived out of for two months, and surveyed the crowd. It was approaching 7:30 on a recent weekday evening, and Godin was getting worried.

“I work and I come back here and see new faces, and it’s like, ‘Will I get a bed tonight?’ ” she said. “Normally we’re in the door by 7, but tonight I don’t know.”

She and scores of others queue up outside the Oxford Street Shelter, hoping to be one of the 218 people who are handed a sheet and a blanket and assigned a 3-inch-thick foam mat to call their own, if only until morning. If they’re too late, they may be offered only a chair to sit in through the night.

Most Americans will never spend a night like Godin and other Oxford shelter residents do, forced to clutch one’s belongings and eke out brief stints of sleep, exposed to the sounds of other people stirring, including some who have been drinking or using drugs and others who can be delusional or violent.

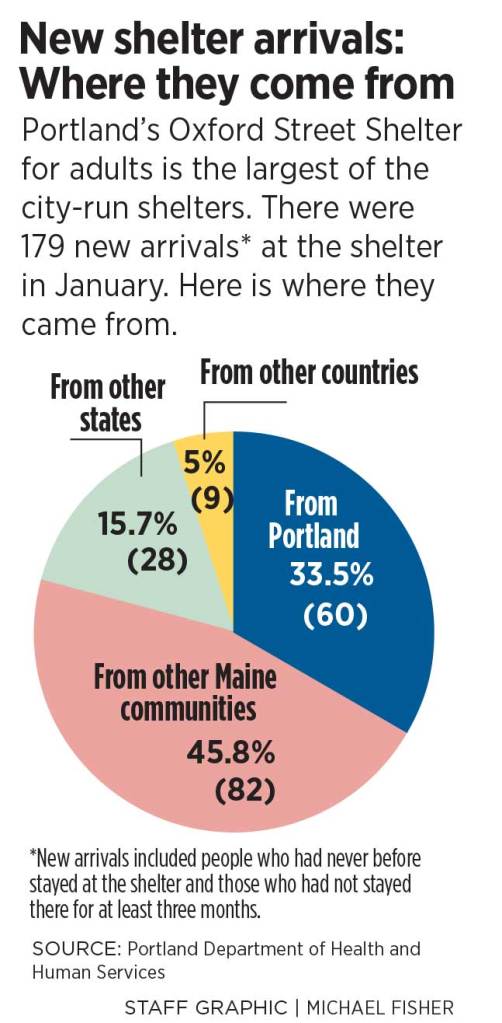

Portland’s homeless shelters have been at the center of a clash between the city and the state Department of Health and Human Services.

In February, state officials criticized the city for using state General Assistance funds to operate shelters even though not all the people sleeping in them qualify for the aid. Gov. Paul LePage and others held that up as the latest example of Portland being overly generous with state money.

City officials, however, have argued that the state is reversing a 30-year agreement that Portland would bill the state to operate shelters that have become a refuge for people from around the state, including some who have mental illnesses and lack access to other community support services.

Although the shelter is meant to be a transitional refuge, some guests have racked up hundreds of nights there.

Godin hopes never to be one of them.

Two weeks ago, with the help of her case worker, Godin was hired as a housekeeper at a South Portland hotel, where she works full time for $8.75 an hour. It is her best shot to escape homelessness and Oxford Street, where comfort and rest are relative terms.

Her days begin with a wake-up by staff at 6 a.m., giving her time to beat the rush for bathrooms and showers that happens just before the rest of shelter occupants have to vacate by 7:30 a.m.

Godin catches a 7 a.m. Metro bus to the Hilton Garden Inn near the Portland International Jetport. By 8 a.m. she is on the job, cleaning rooms, making beds, vacuuming and replenishing bathroom towels.

Her job gives her time to think, time to be alone. More importantly, she said, while standing outside the shelter, “It keeps me away from here.”

In a typical work day, she’ll tend to at least 14 rooms. She hopes to pull overtime hours this summer, when tourists mean a greater need for her services.

After two weeks on the job, Godin was excited to cash her first paycheck and open a bank account. They are steps that she knows will bring her closer to independence, and farther from the hectic malaise on Oxford Street.

The contrast between days spent pushing a cleaning cart stacked with fresh linens down hushed hotel hallways, and her nights spent amid the disruptive, sometimes-intoxicated shelter guests have begun to wear her down, Godin said. She has been sleeping at the shelter for two months.

“I don’t like coming back here,” she said. “It’s getting kind of old.”

MANAGING ARRIVALS, CLIENT ISSUES

Every night at the state’s largest homeless shelter, clients begin checking in at 6:10 p.m., but the queue forms next to Oxford Street at least an hour earlier.

Beds are assigned in a tiered system that gives first priority to people with physical or mobility-based disabilities, followed by people with medical issues. Next to be checked in are women, followed by the majority of clients, men.

All guests who stay the night must enter through a glass side-door that leads to a front desk.

Most shelter clients are repeat customers, and have already been assigned a white, bar-coded plastic card that a member of the shelter staff scans with a computer. The card not only identifies the shelter client, but allows the city to track who is present and how many nights they’ve been there.

General check-in usually starts about 6:30 p.m., and continues until the shelter’s 9:30 p.m. curfew. The only break comes at 7 p.m., when shelter staff gather in a tiny back office for their nightly meeting. Sprinkled between the mundane discussion that could come from almost any workplace – talk of trash collection, parking, break times, an update on replacing some furniture – are aspects wholly unique to the rough-and-tumble clientele the shelter serves.

The shelter’s interim director, Angela Havlin, speaks first, and starts with the good news. A staff change means three employees who are lower on the hierarchy get to move up into new roles. Because Portland is under a hiring freeze, however, the promotions are temporary, another reminder of the tenuous financial state of the city’s shelter operation.

After the housekeeping items, Havlin delivers a gut punch. The night before, a long-time shelter client died, Havlin said. The cause of his death wasn’t clear, but he was not at the shelter at the time.

“I know people knew him pretty well,” she said. “People did a lot to try to assist him.”

Although there are more than 200 regular clients, the staff knows most of them by name, and the night-shift team leader on this particular evening, Jason Chan, gives updates on a few of them who need extra attention. Chan has been a shelter attendant for three years, but at only 26, his calm demeanor makes him seem older.

Chan runs through the list of disturbances the night before. One client made unwanted sexual advances toward another person and spat at a shelter worker; Portland police had to be called. Another client was served with a criminal trespass order preventing him from returning to the shelter after he refused to listen to shelter staff and threatened to shoot someone in the head. A third client was ejected after he threatened and then attempted to assault someone.

“He likes to present ETOH,” Chan said, an acronym used by staff to indicate someone seems intoxicated. (The term is chemical short-hand for ethanol, the inebriating ingredient in wine, beer and liquor.)

A fourth client was scheduled for an intervention the next day. Chan reminded staff to take note of any abnormal behavior by a fifth client, a man suffering from an untreated mental illness and whom staff were attempting to have admitted to Riverview Psychiatric Center.

“He’s another one. Document, document, document,” said Brian Marchant, a shelter counselor. “Getting him into a hospital … is a priority.”

A sixth client, also suffering from apparent mental health problems, has been showing signs of increasingly delusional thinking, Chan said.

But Havlin interrupted him.

“We’re out of time,” she said.

Outside, the line for a bed was growing.

HIGH DEMAND, HANDLING OVERFLOW

At full capacity, the Oxford Street facility can house 143 people. Although staff call them “beds,” shelter guests sleep on nothing more than plastic-coated foam mats, measuring roughly 2 feet by 6 feet and a few inches thick. When those fill up, shelter staffers lay out 75 more mats at Preble Street, a nonprofit group that runs shelters and a food pantry. The final overflow facility is at the General Assistance office at 196 Lancaster St., where up to 75 additional people can spend the night dozing upright in chairs.

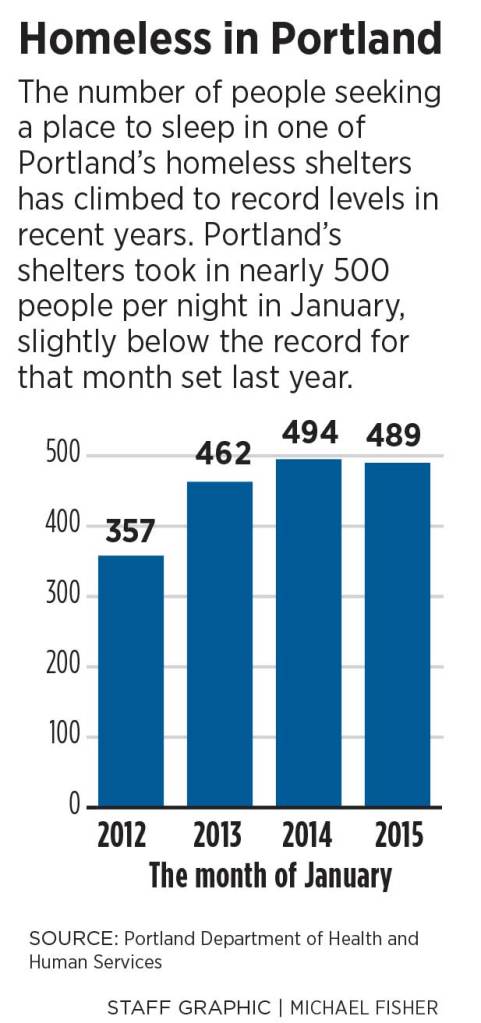

The Oxford Street shelter is part of a network of city-run and privately run facilities in Portland – others serve teens and families, for example – that are serving nearly 500 or more people a night.

A crew of 10 or 11 staffs the Oxford Street Shelter each night. Some evenings the complement feels like enough, Chan said, but a single absence can complicate planning.

For instance, to safely open Preble Street each night for the overflow, two shelter employees must be present. Another staffer is diverted to the General Assistance office to watch over as many as 75 people.

To make sure the facilities are staffed when needed, the shelter relies on 15 per-diem employees to fill out the daily roster.

During the overnight shift, staffers monitor each of the Oxford Street Shelter’s three floors. On average, there are four or five disturbances each night, ranging from verbal disputes that can be de-escalated to full-blown fights or confrontations that require a guest to be asked to leave.

If at all possible, staffers try to handle problems without police intervention. Calling the police usually means that someone who came for a place to sleep will be turned out into the cold, cited or arrested.

If there are repeat offenses, the shelter can bar someone from returning, sometimes via a criminal trespass notice.

It’s those disturbances that wreak havoc on Godin, whose work days frequently stretch to 10 hours, including travel time.

Where she will sleep is not her choice. Mats are randomly assigned for most shelter guests, other than those who require special accommodations. Each is numbered, and depending on where she is assigned and who is sleeping nearby, rest can be elusive.

HOUSING VOUCHERS HELP DOZENS

Godin, who is 40 years old and originally from the Sanford area, said she’s been homeless twice before.

She has two children, ages 15 and 20, who do not live with her. She was married about eight years ago, although it didn’t last and she expects to finalize the divorce next month, she said.

Three years ago, she was living with her parents. But when they both passed away, Godin had a falling out with her siblings and was without a place to live, she said.

She stayed in a shelter briefly until she moved in with a boyfriend. The two stayed together until recently, when the relationship began to fray. Godin landed in the shelter after her boyfriend and other tenants were evicted from a pair of Wilmot Street apartment buildings when they were purchased by a new owner.

Godin is now building up some savings and hoping to qualify for a state-funded housing voucher program that has moved dozens of people into housing in the past 18 months.

The program requires that she pay 30 percent of her income in exchange for a monthly rental voucher, good for one year. She hasn’t applied yet, according to the city, but plans to get involved as soon as she can assemble the required documentation. Most of her personal documents were lost when she left her former apartments, she said.

In the program’s 18 months of existence, 118 people are somewhere in the process of either applying for housing or living in a subsidized apartment. Thirty-two people completed the full 12 months, with a handful of others choosing to end the subsidy earlier because their incomes increased, according to the city.

Godin also gets breaks from the shelter by visiting her former boyfriend at his new apartment a couple of times a month, she said.

Although no longer a couple, on a recent afternoon in the Oxford Street day room, Godin and Craig Campbell conversed in a corner, before retiring outside to smoke cigarettes that Campbell rolled for them.

“We’re still friends,” Godin said. “We help each other. It’s not easy. I just take it day by day.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.