Next to the things you need, like or want in even the finest grocery store are much larger quantities of things you don’t need, don’t like or don’t want.

If everything is pre-selected (have you noticed how hip the word “curated” has become in the retail world?), then it’s worth asking if our sensibilities are still sharp enough to find diamonds in the rough.

After all, if you want to find a needle in a haystack, what better way is there than to throw yourself in?

This is how I think about open-call art exhibitions – but many highbrow members of the art audience are intimidated by low-barrier shows because they are challenged to sift through the good, the bad and ugly on their own.

The “Rumpus Revival” now on view at Engine is an ideal setting to give your sensibilities such a workout. It’s lively and fun with an often wacky installation of about 200 works of art.

Among the motley ranks are artists whose works are held in important public collections. There are also works by inexperienced amateurs that successfully balance authenticity with charm (I’m thinking of you, $30 “Platypus”). But most interesting to me are the promising artists I had never seen before.

Last year, for example, I happened on the work of Jabez Malmude when I juried a USM show and awarded him top honors. His “The Irons’ Cow” at Engine makes the case why he heads my watch list. Most impressive is the interplay between Malmude’s mark-making and his sense of rhythm created by dividing his subjects into subtle cubist structures. It first looks like the pencil flies in his fingers, but on closer examination you see Malmude’s drawings require intricate planning, patience and plenty of time.

Francine Schrock’s “Arrival” and “Nearing” were among my favorite works in the show, and they marked a sea change in my understanding of her work: The two small foot-square panels are monochromatic (phythlo blue and white?) cloud-oriented mountaintop landscapes that showcase some truly impressive brushwork. It is interesting to see these just above a photo on canvas stretched like a painting – a medium that has probably surpassed “Giclée” (affected rhetorical camouflage for “digital reproduction”) for eliciting disgusted responses from professional artists. (We have none other than Graham Nash of Crosby, Stills & Nash to thank/blame for this technological innovation.) Walter Buczacz’s sunset scene, after all, looks quite like a painting and may fool some casual viewers. Responding to the wrap-around logic, however, is a brilliant little painting of digital numbers by Kenny Cole – a sort of ironic reverse camouflage.

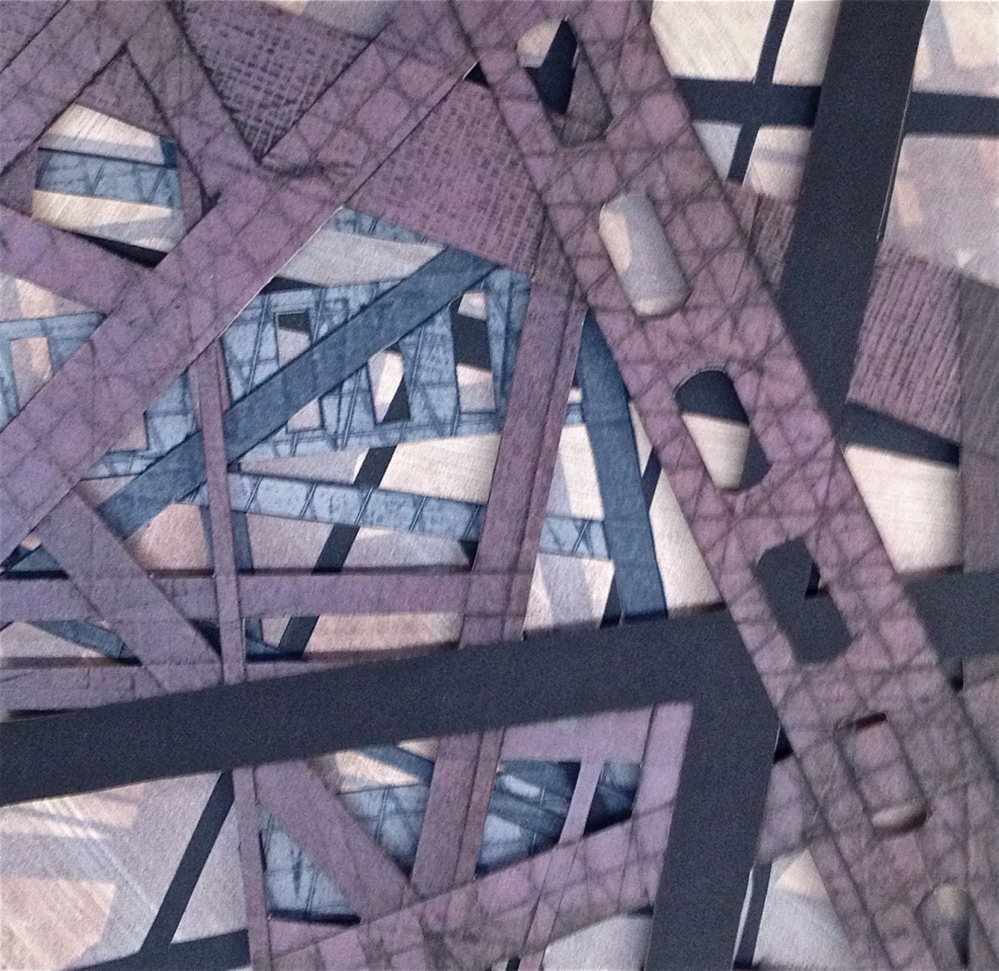

A few of the other notably strong works include: Chris Beneman’s geometrically elegant cut and layered ruler-ish collagraph and monotype, Nancy Barron’s “South Along the Tracks” with its rhythmically thick and chewy surface, G. Bud Swenson’s powerfully iconoclastic repurposed-Bible collage painting, Jeffery Ackerman’s brilliantly and creepily Magritte-like sepia drawing “Knight’s Move,” Dorette Amell’s savvy and striped “Psychology of Reversed Persons” and Rachael Eastman’s mystically reductive landscapes.

Many of the strongest works in the show are by artists who are new to me.

Jocelyn Toffic’s “The Collector” is an assemblage in a small wall-mounted (insect collecting?) case filled with scores of tiny, mounted clay penises labeled with names like “The Cellist,” “The Eunich” and “The Underwater Welder.” Between the labels, the diminutive scale amplified by the attached magnifying glass and the idea of detaching all these samples from their former hosts, “The Collector” is a laugh riot. (And I don’t even want to know about the brown smudge remnant that is all that remains of “The Handful.”)

Jarid del Deo’s “Brush Pile” is a nicely painted scene whose humble subject settles quietly into the show’s visual cacophony.

Keiren Valentine’s centrifugally opening box (a cyanotype?) offers slick motion to a geometrically impressive image.

Two painters working in colorfully abstract modes whose pairs of works make the case to keep an eye out for them are John David O’Shaughnessy and Amanda Hawkins. O’Shaughnessy’s paintings have an appealing ’80s-like splintery sparkle and Hawkins’ have a savvy and sophisticated softness that allows them to flow seamlessly between forms and colors.

Also standing out from the less accomplished (though not necessarily less interesting) works, is a group of decoratively appealing pieces. There should be a race between restaurant owners to see who gets to buy Jessica Chaples’ handsome “Lobster” mixed-media painting for $275. And Laurie Smith’s ink and dye on unprimed, collaged canvas scenes are some of the most stylistically original landscapes I have seen in a while.

Open shows remind me of the scene from “Moscow on the Hudson” in which Robin Williams plays a Russian immigrant who, after a lifetime of bread lines, walks into an American supermarket – and, overwhelmed, promptly faints. A panopoly is just a different kind of obstacle between you and what you’re looking for.

If you doubt the worth of open, un-juried shows, then you should read about Marcel Duchamp’s famous “Fountain” – one of America’s most influential works of art. It wouldn’t have happened with its unjuried birthplace.

There has been plenty of talk recently by artists who want to mount an open show to respond to the Portland Museum of Art’s decision to turn away from the William Thon Bequest-funded juried biennial for a more access-oriented curated biennial.

Thon’s bequest was always about a juried show. According to the Portland Press Herald news report published on March 23, 2001 announcing the bequest: “Thon’s will directs the museum to use the funds for support of its juried biennial exhibit of Maine art, but the money is not restricted to that use. (…) In his career, Thon found juried exhibits to be a big help, (erstwhile PMA chief curator Jessica) Nicoll said.”

In other words, while the money was not restricted to being used for the juried biennial (the news report proffers “…and possibly programs in support of American art”), it seems clear Thon never considered a biennial model other than a juried exhibit.

I suggest to those calling for an unjuried show go see the “Rumpus.” An open show, after all, is a very different animal than a juried one. And there were reasons why Thon wanted the PMA to have a juried biennial instead of just another curated show. Open shows (anything goes) and curated shows (curator gets what curator wants) are easy, but juried shows rely on both high standards and the relationship between the institution and the art community. Almost every show we see at galleries and museums is curated, and non-profits across the state – not just Engine but SPACE, the Harlow and others – can mount successful open shows, but very few institutions have the reach to mount a credible juried show. I particularly lament the PMA’s rejecting the spirit of the Thon Bequest because no one in Maine could offer a more credible and important juried show than the PMA.

For the sake of Maine’s art community, I hope they return to Thon’s vision for the next biennial.

Curated, juried and open shows have very different relationships to the community. And they all have their places. We must challenge ourselves to understand the differences between these varying modes as well as their histories instead of sweeping standards under the rug for the easy road of consolidation.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.