Who, and what, is old? When does a child become an adult? What does an adult have, what does she aspire to, what can she communicate that a child has not, does not, cannot? We know adolescents with the wisdom of elders, and leaders of nations with the maturity of kindergartners. All depends on upbringing and context. As with people so with vines, the cardiovascular system of wine.

Wine folks speak frequently about grapes, soil, climate. It’s less often that one hears about vines, except when a label notes that the wine in a particular bottle came from “old vines.” For a long time now I’ve been trying to figure out what this means. No one seems to know.

Or at least, no one seems to agree. In even the world’s most regulated, nit-picky wine regions, with rules about grape varietals, alcohol levels and aging time, vintners seem to have carte blanche to call a wine “old vines” (or “vieilles vignes” in France, “vecchie viti” in Italy, “alte reben” in Germany and Austria, and so on), without mentioning how old. Vintners who farm vines that can comfortably be called “old” tout them as such; vintners with younger vines rarely boast of them, though some explicitly dismiss the assumption that older is better.

Anyway, we’re in a gray area, and ought to refer to “average vine age,” since most vineyards contain vines that were not all “born” at the same time. Some vines get sick, some die. Sometimes a vintner will increase vine density in a given vineyard, adding vines and rootstock to a plot of land that has comfortably housed other vines for decades. Most wines blend grapes from vines of differing ages.

It’s probably safe to say that vines younger than 30 cannot be called old. Beyond that, the terminology gets chaotic. In Australia’s Barossa Valley, for instance, shiraz vines older than 35 are classified as old, but then there are survivor vines (75 years old and more) and even centurion vines (over 100). Genuinely old vines are rampant in Spain, and so anyone there who says “viejo” should be talking about 70 or more. In Campania, Italy, there are vines older than 150; are the 75-year-olds old?

Is it fair for an Oregon producer to call a special bottling “old vines” if it came from the 25-year-olds? Maybe, since Oregon’s wine industry is so young that most of the wines from there that we taste are from vines barely over 15 years of age. In Muscadet, France, there are extraordinary wines made from “old vines” that are around 40, while just a bit farther east along the Loire Valley, in Sancerre or Vouvray, due to different soil compositions the old-vines bar is raised and 40 doesn’t cut it.

Other questions relate to grafting. Is a 15-year-old vine grafted to 130-year-old rootstock capable of making an “old vines” wine? Many such wines come out of California, among other places, where extant old roots that were resistant to phylloxera still provide the home base for newer generations of ancient vineyards.

I’ve drunk a fascinating wine from Chile whose paìs grapes hung on 20-year-old vines grafted to 300-year-old roots. The wine (cheap, though not yet available in Maine) underwent carbonic maceration and therefore retained a delicious and digestible freshness even as it transmitted half-hidden signals from a world long past.

That, by the way, is what old vines do. They produce wines delivering an inimitable combination of intensity and mystery. One feels one is being stared at, assessed, even as the wine itself does not allow you to return the gaze. Successful old-vines wines penetrate, without fully revealing.

Flavor-wise, old- and young-vine wines do not align along the fruit/earth axis. There are fruity wines from old vines, such as many old-vine zinfandels; there are earthy wines from young vines, such as many Chiantis.

The older the vines, the deeper they have tunneled below the surface soils and the longer they have explored and conveyed what they’ve found. But it cannot be claimed that the deeper a vine burrows, the earthier the flavors it will return to its grapes. The spectrum is one of intensity rather than flavor, how rather than what.

Like “old,” the word “intense” garners respect. We respect old people and old houses; we admire intense athletes and actors. But intensity by itself is no virtue. Fewer grapes can grow on old vines than on young, so whatever the roots and their tendrils grasp goes into less fruit. This leads to wines with more concentration of flavor and aroma, but that’s a good thing only if the primary material – the information embedded in sunlight, soil, water – comes together in harmonious ways.

An old-vine wine that concentrates and intensifies unpleasant attributes, and lacks the refreshing, juicy, upfront quality most efficiently transmitted through young vines, is surely intense – and surely bad.

The Bobal deSanjuan 2012 ($13), from Valencia, Spain, is intensely good. The bobal vines are an average of 70 years old. The wine has a bold, ripe black fruit character, but as the wine arrives at its middle stage on your palate, something very different emerges: a tobacco-y profundity and forested quality you weren’t expecting at first taste. Good old-vines wines do this: They offer more and more, drawing you in patiently and in small steps.

Strangely, this can happen in even the most delicate sorts of wines. Take Muscadet, which is usually fine and light, though somewhat watery and lacking presence. The Domaine Luneau-Papin Muscadet Sèvre et Maine “Pierre de la Grange” Vieilles Vignes 2013 ($15) brings complete presence, though on tiptoes. First, whispers of peach and heady floral aromatics. Then – again, in the mid-palate – a deep-rooted, schist-laden mineral drive emerges. None of this happens obviously; nothing in the wine is impatient to speak. Yet it does not let go.

The list of excellent old-vine wines, all along the price spectrum, is vast. The grenache-based Vacqueyras from such excellent producers as Domaine Les Ondines ($19) and Domaine Le Sang des Cailloux ($37) seem to conjure up entire National Geographic documentaries on the earth’s mantle. The Beaujolais of Stéphane Aviron, even his Villages 2013 ($15) from relatively young (for him) 50-plus-year-old vines, is light-medium bodied and bone-dry, but expresses a thrilling precision and length.

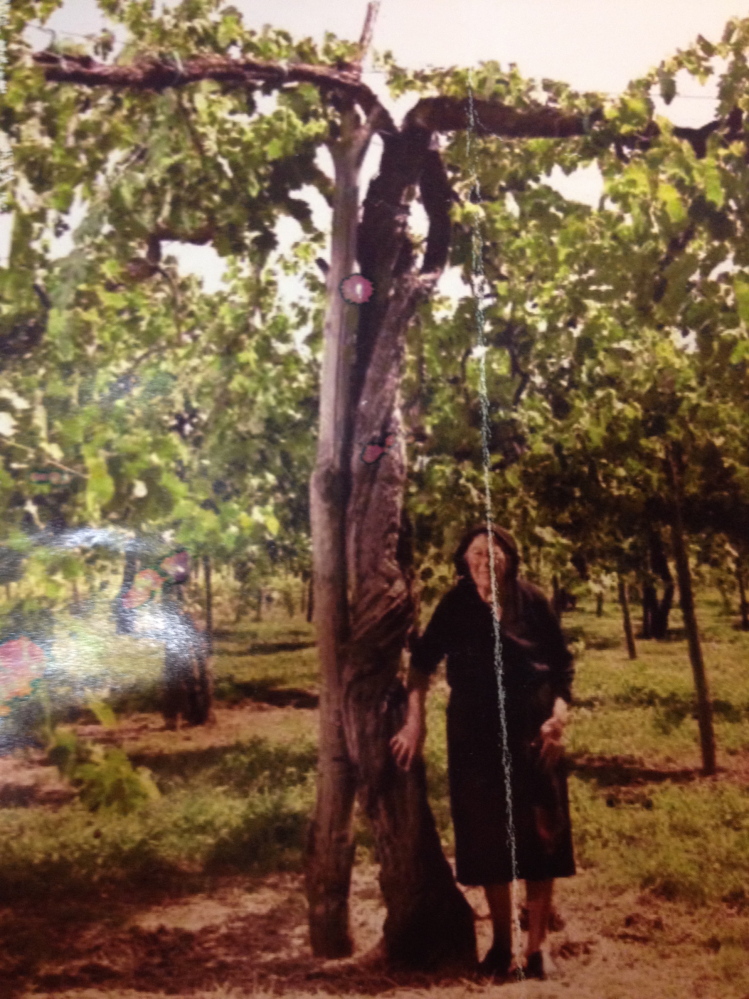

The Domaine de la Noblaie Chinon “Les Chiens-Chiens” ($21), off vines varying from 40 to 80 years old, is muscle-bound and peppery, tremendously full and satisfying though with uncommon elegance. South African chenin blancs, many of them off old bush vines that grow close to the ground, carry a weight and substantiality that could knock you over if you’re not careful. Old-vines zinfandels of disorienting mystery and darkness (and sometimes, strangely, the opposite) are many, and will serve as the subject of an upcoming column.

What do all these wines have in common? Steadiness and unhurried power. They abide. Old vines stabilize the vagaries of weather from one vintage to the next, gathering phenolic compounds and accruing sugar levels slowly, consistently.

Their roots are deep enough to avoid soaked soils in rainy seasons, and they can absorb tiny reserves of water hidden way down in the subsoil if a drought parches the vineyard. Whatever happens, old vines have seen it before and they know what to do.

This doesn’t guarantee that you will like the wine. But it offers better odds than young vines can that the wine will be true, that it will arrive at a place of comfort and confidence.

This is hard to quantify. But if you know anyone, whatever her age, who exudes these traits, you know what I mean.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.