In the first few pages of Jack London’s 1904 “Sea-Wolf,” the gentlemanly protagonist, Humphrey van Weyden, is cocooned by his personal understanding of navigation as a “purely mathematical” endeavor – the stuff of books and charts rather than savvy pilots. Of slight build and literary persuasion, he is a ferry passenger in the busy San Francisco bay during a thick fog.

There is little to see and less to make sense of – only the frantic booms and trills of horns and whistles. He is joined by a wooden-legged old sea dog who calls the game in real time – from experience rather than erudition. The old man senses catastrophe and calls its coming. Humphrey never even sees the ship that strikes the ferry, sinking it.

Humphrey is overwhelmed by the screams of the panicking crowd, but just moments later, he is dangerously alone in the fog, drifting out into the Pacific in the freezing ebb tide waters. A schooner sails almost over him and only by the chance glance of its master is Humphrey is pulled from the water.

“Why didn’t you call out?” is the question asked of him.

This is literally the story that swirled through my head as I first went through Michel Droge’s “Tiny Catastrophes.”

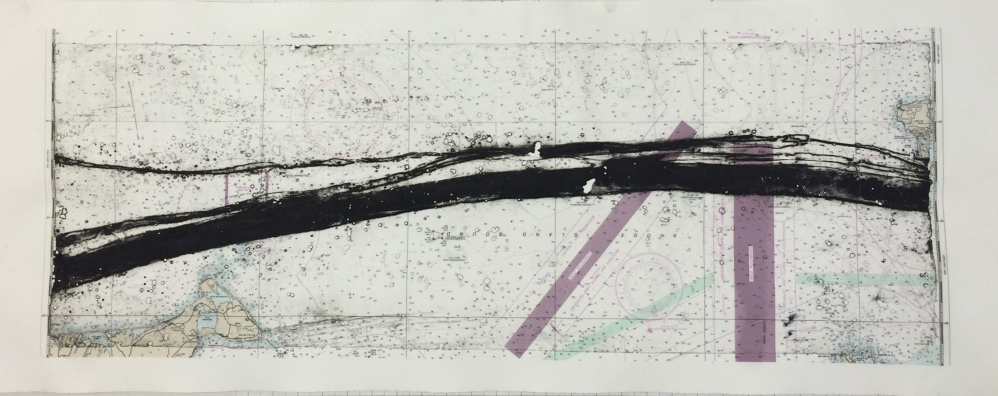

“Catastrophes” is a very strange and rewarding painting exhibition. It’s strange because it combines subtle and refined abstractions with almost cartoonish small scenes of coastal trouble. And amongst these dominant forms are ranks of outliers: an atmospherically soft landscape, a coastal landscape rendered in a traditional painterly-realism style, a suite of richly bleak coastal etchings and then finally a map of the Atlantic off Rhode Island with a grimly sweeping black stroke slashing through it.

It is this last work, titled “Your Heart,” that (for me) redefines the underlying mood of the show. It is not the ebb and flow of a fickle lover. It is mortality, left adrift like unfound flotsam.

“Catastrophes” may hint of climate change (a shadow easily dredged from the work, but reinforced by Droge’s exhibition statement), but the work tilts away from such broad phenomena toward the subjectivity of personal experiences. Even the “s” on the title hints at stories rather than a singularity. (Think Peter Precourt’s “Katrina Chronicles” rather than Tom Hall’s “clearcuts.”)

What knits “Catastrophes” together is a rare sensitivity toward subjectivity.

To begin, Droge’s atmospheric abstractions had caught my eye in recent shows. Pieces like “Distant Anthem” with its dreamy atmospheric softness offer lush and even plush repose for your eye. And they work because Droge doesn’t get too blurry or overly heavy with the paint. They are like chaos-lite – free from the fear of solid things into which you might crash.

Paintings like “Anthem,” the larger “Milkweed” (imagine the silky explosion of the pod contents) or the waking-from-sleep’s soft cushion of “Morning,” reach out to welcome the viewer’s subjectivity. That is to say, Droge doesn’t try to force her emotional engagement with the work on us. She seems to leave us alone with our own readings and our own feelings. And as a fan of abstraction, I appreciate that: I like to enjoy non-objective paintings my own way.

But Droge leaves us a trail we can choose to follow. If “The Year the Ocean Froze,” for example, were untitled, we might remain in the experiential mode of Droge’s atmospheric abstractions. But the title puts us within an annual rhythm that not only adds a bit of nostalgia, but makes all the water (in the entire show) colder. That made me, for example, fear then for the figure in “Life Saver” whose lobster boat is sinking; the title in this case is not necessarily some heroic agent – it could just mean the orange flotation device holding the figure in the freezing water.

Droge’s etchings reinforce the cold. Titled “February” and “Late February,” two 4-by-12 inch prints show long forgotten pilings from a chilly, near-water perspective. Their feel is like a barely scratched drawing, long beaten by time – like wisps of memory of poignant, far-off feelings. They have substance, but it is not physical.

The largest painting offered me the biggest surprise. When I first looked at “Night Bridge,” I saw a night-softened coastal landscape dreamily looking toward shore. But getting through “Catastrophes,” my hackles were up. At some point, my eyes shifted from repose into lookout mode. Certainly, it’s a handsome painting, but it’s also an effective vehicle for shifting perspectives. The night will do that: Sometimes the children are nestled all snug in their beds, and sometimes the dream of reason produces monsters.

I can’t tell you how to see “Tiny Catastrophes” because there is no right way. There is only what inspired Droge, the works she made and then what you will bring when you see them. It’s a fine thing to put your own subjectivity on the table and then invite others to bring their own. Art exhibitions aren’t mathematics classes, after all, but culture with all of its inevitably tangled roots and branches.

I see a powerful nostalgia (ranging between grim and bittersweet) roiling in “Catastrophes,” but that might be more me than anything else.

Why didn’t Humphrey call out for help? He was too busy dying as ocean cold drained the life from his body. He wanted to cry out, but couldn’t. He wanted to wave his arms, but couldn’t. He was only saved by a chance glance and the humanity – however grizzled – of another man with a sea-experienced eye. I understand that. One June evening, I found myself boom-swatted from the deck of a J/24 class keelboat into the Atlantic waters well off Cape Cod, the sail having caught a rogue gust – an outlier blast on an otherwise windless day. I am a very strong man, but in mere minutes I was too weak to lift myself into anything.

It was a humbling experience: I would be dead if it weren’t for my brother.

Whether the story is about climate change or the people taken by the sea, Droge cobbles a complex narrative knit within an oddly gossamer web. Are we the flies or the spider; the sea dogs or the Humphreys? Or is it that Droge’s work clicks the moments away past the point when ethical actions – or even morality – still matter? After all, naiveté has a threshold – which Humphrey managed to cross – but sometimes it’s simply too late.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.