Sufjan Stevens rose in popularity in the mid-2000s by stitching modern folktales to kinetic, sometimes overstuffed compositions. His gifts as a writer and his ambitious musicianship were undeniable, but his persona was distant; he often cloaked himself behind colorful costumes, gimmicky concepts, and grandiose mythmaking. He shed these bells and whistles for “Carrie & Lowell,” his 2015 album written in the wake of his mother’s death and the inspiration for his current tour. No longer content to keep listeners at arm’s length, Stevens used these emotionally naked songs to draw us close – at times, uncomfortably so.

It’s slightly ironic that he managed such intimacy in his largest Portland concert to date. His threadbare ruminations of a mother lost to the world and a son lost in the world might initially feel too personal for a regal venue such as Merrill Auditorium, but such was not the case. Moments when he spiraled into self-loathing, such as the weary death wishes of “The Only Thing,” seemed to shrink the room to fit the scope of his salt-on-wound introspection. Otherwise, the size of the venue was scaled to his emotional ambition, and perfect for an artist hitting a creative peak after taking nearly 40 years to grow into his potential.

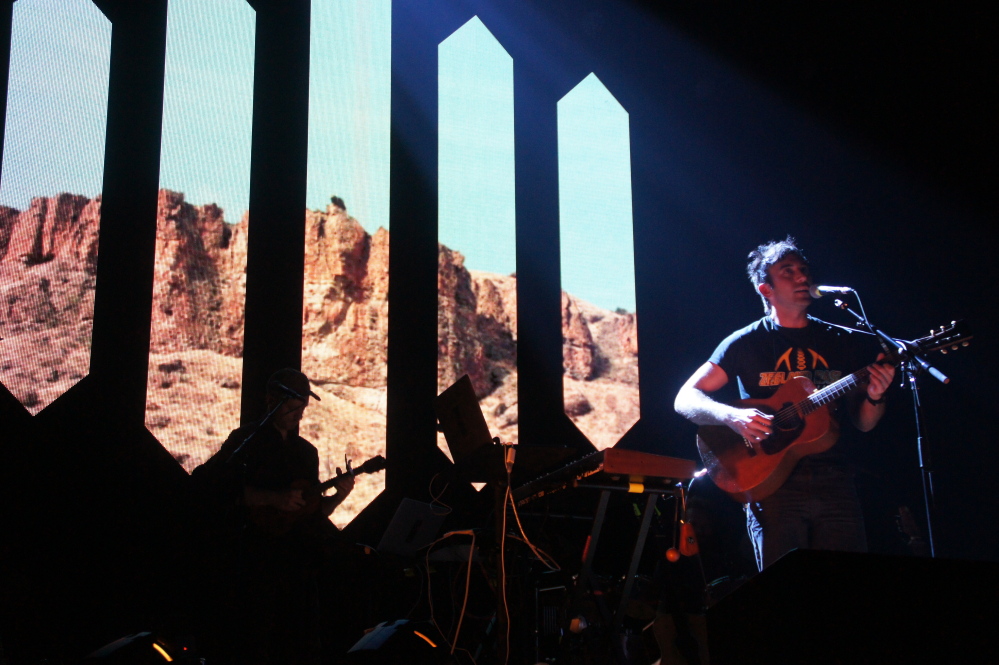

“Carrie & Lowell” can sound minimalist compared to Stevens’ past work, but this is largely deception. The songs feature many shifts in tone, key and instrumentation, but they come with more subtlety on this particular record. In concert, those shifts are more dramatic, as additional backing vocals make the whole room hum and acoustic plucking gives way to outsized blossoming of electronic passages. Many of the songs dissolved into washes of noise that evoked the light passing from one’s eyes at death, or the big bang at the beginning of all things. The climax of “Blue Bucket of Gold,” with overbearing sonics accompanied by bright lights fractured by spinning disco balls, was the most impactful of these moments.

Stevens played nearly all of “Carrie & Lowell,” and with the exception of the extraordinary “John Wayne Gacy Jr.,” his older songs seemed quaint and trivial by comparison. None of them got a big to-do in the stage presentation. This is clearly so he could have the flexibility to rotate different older songs in and out of the set as the tour progressed, but the lack of attention to their presentation was pointed compared to the care given to the pastel lights and projections of home movies and landscape photography during the “Carrie & Lowell” numbers.

This presentation was most effective during the climax to “Fourth of July,” which featured Stevens singing, “we’re all going to die” in increasingly desperate frequencies. As he did so, beams of purple light swirled around the audience like great fingers, gently touching every person in attendance as if to say, “yes, you too.” The projected images behind the band, which had been showing magnified shots of what looked like bone marrow, collapsed into a red flatline at the conclusion.

There is nothing minimalist about that, but the song reveals its true message in a subtle fashion: The important line is not “we’re all going to die,” but “make the most of your life, while it is rife, while it is light.” The takeaway from the concert was that death is ultimately a positive aspect of life, and life is worth celebrating. Stevens came away from the death of his mother and the accompanying reflection on his troubled childhood with a renewed purpose in life, and the music he’s now creating confirms that he’s making the most of it.

Robert Ker is a freelance writer.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.