What happens when mature adults emulate children’s art? Obviously, there is no single answer, but it’s an interesting question because the outcomes vary so wildly. Usually, the response fails before it even gets out of the gate because the artists who set out to emulate children’s art cannot be naive: They can only emulate naivete. In other words, professionals who set out to make what looks like children’s art make something both contrived and fake-feeling.

Generally, making art is like a golf swing: If you have to think consciously about all the components, you’re lousy.

But you also have to know what you’re doing. And this is where art is less like golf than it is like language. Kids know what appeals to them and so they have a visual language. For any given child that varies, but imagine a child who likes big patches of bright colors, clear lines, figures in a landscape doing something – in short, cartoons.

One problem with adults is that they are far less likely to have a visual language that they understand and that is within their grasp.

On view now at 317 Main in Yarmouth (an amazing public space, particularly if you want to introduce your brood to music) is one of the few exhibitions I have seen that successfully follows work by smart adults into the world of children’s art.

It’s a two-person show, and the simple reason for its success is Abbott Meader. Meader has one of the most unique creative minds in Maine’s artistic history. He soars at most everything to which he puts his hand: oil painting, pastels, sculpting clay legs for hanging pots, raku, film (“Deep Trout” is a Maine classic), collage, acting (best Bill Sikes I ever saw) and so on. But what makes Meader particularly remarkable is his generous warmth: Meader spent the bulk of his career as a Colby professor, and it has been a career well-spent. He was successful as a teacher because he respects and likes his students, young people and people in general. When Meader looked at his own children’s art, he was inspired by their magic and mystery.

Importantly, Meader only makes works inspired by children’s art once or twice a year. The rarity of his working in this mode is probably the reason why the series is so successful. To be authentic in the way kids are, it doesn’t work to have a well-worn path or a recipe or, in other words, an academic approach.

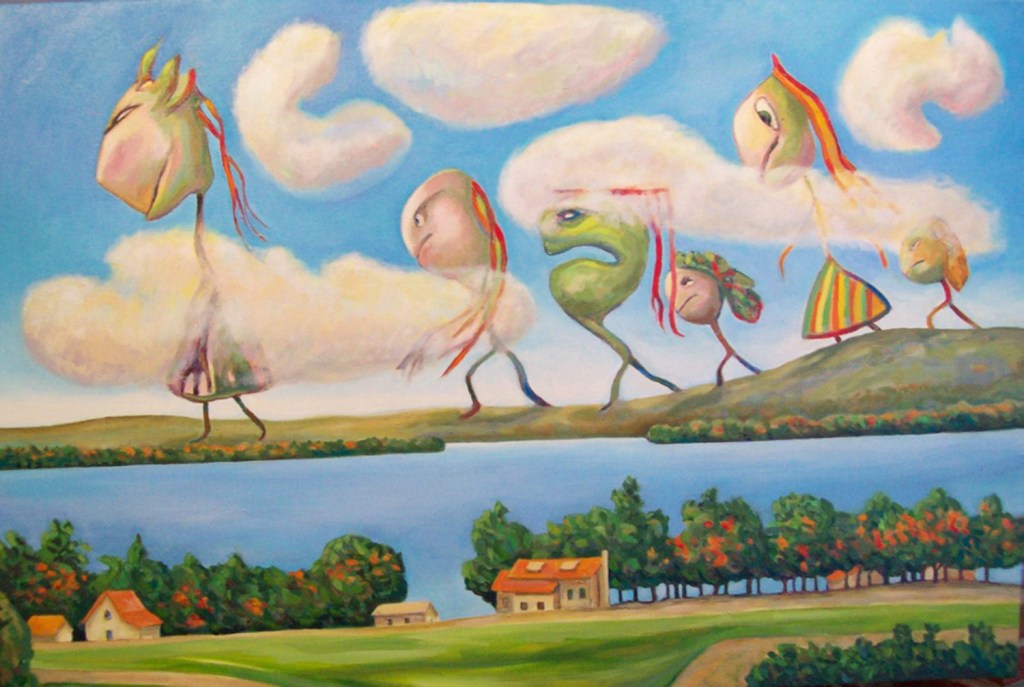

One of most interesting pieces at 317 Main is a large, recognizable (to me at least: Belgrade Lakes) landscape painted in a bold hand clearly informed by N.C. Wyeth and American impressionism. But walking single-file from right to left in the deep background is a troop of giant, dreamlike figures. It’s an arresting image – like a child’s daydream at the museum. And while the accompanying explanation of the source deflates this particular piece a bit, it sets a magnificent table for the rest of the show.

Colby sculpture professor Harriet Mathews once sent the Meaders a postcard. One evening many years ago while Meader and his wife were out to dinner, one of their kids drew these figures on the card. Meader doesn’t pretend to understand – and I think pedantic parents are the bane of budding artists – rather, he is fascinated by the (now) unanswerable question: Who are they?

These figures, like the others in the show, come to us like real people – with their own, untold back stories and, therefore, agency. In this sense, they are no less real than a man you pass in the street.

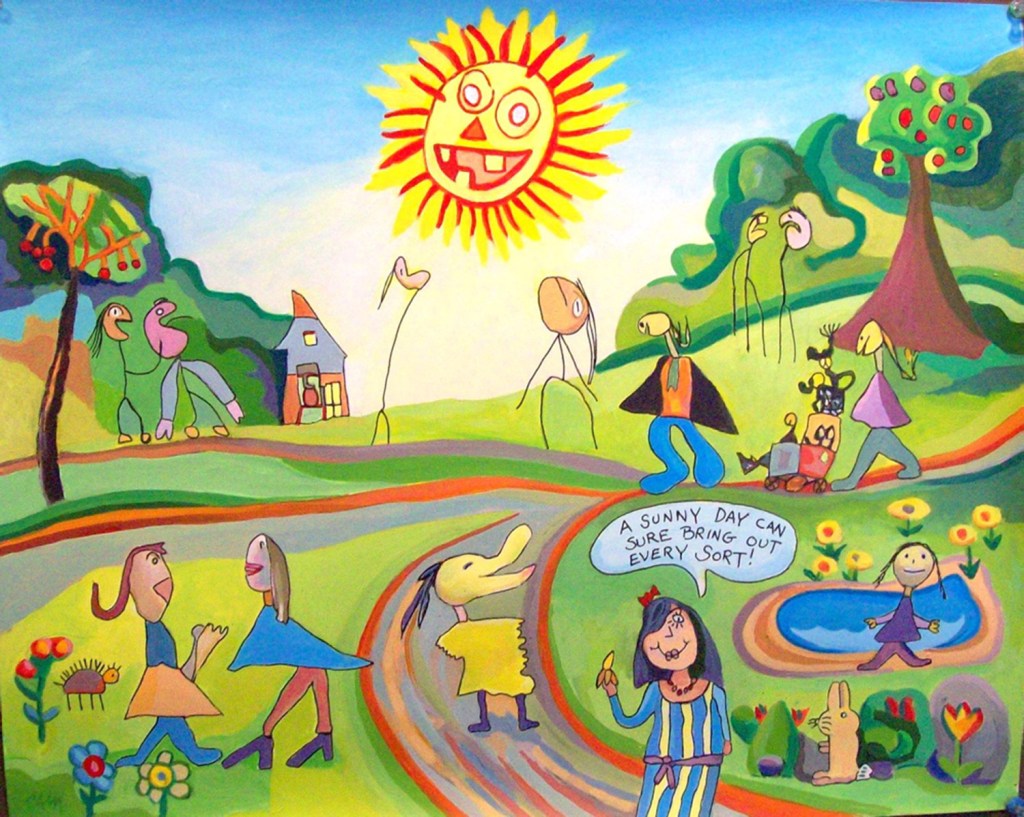

And like the rest of the works in the show, “In the Fall/Ridge Walkers #3” doesn’t play by the same rules as the other paintings. We tend to see landscapes (suns tend to smile) in which there are several figures rendered in disparate styles (stick figures, blobs, etc). To a certain extent, this is the message of the show: Kids are natural postmodern surrealists. This point is particularly well celebrated in one painting in which a well-developed cartoon woman says (via voice bubble) “A SUNNY DAY SURE BRINGS OUT EVERY SORT!” All around her is a compendium of kid art styles that acts like a developmental art diary, moving from stick figures to the solidly stylized – like the “grown-up” speaker.

In “At the Maiden’s House,” a knight charges in from the right, sword in hand, to save the maiden who is standing in her open doorway imagining an illegible something. Monsters of a young hand gather to the left as a large, fishlike dragon flashes his giant maw in the center. I thought of Raphael’s “Saint George,” but it could be any (or every) princess and her dragon captor.

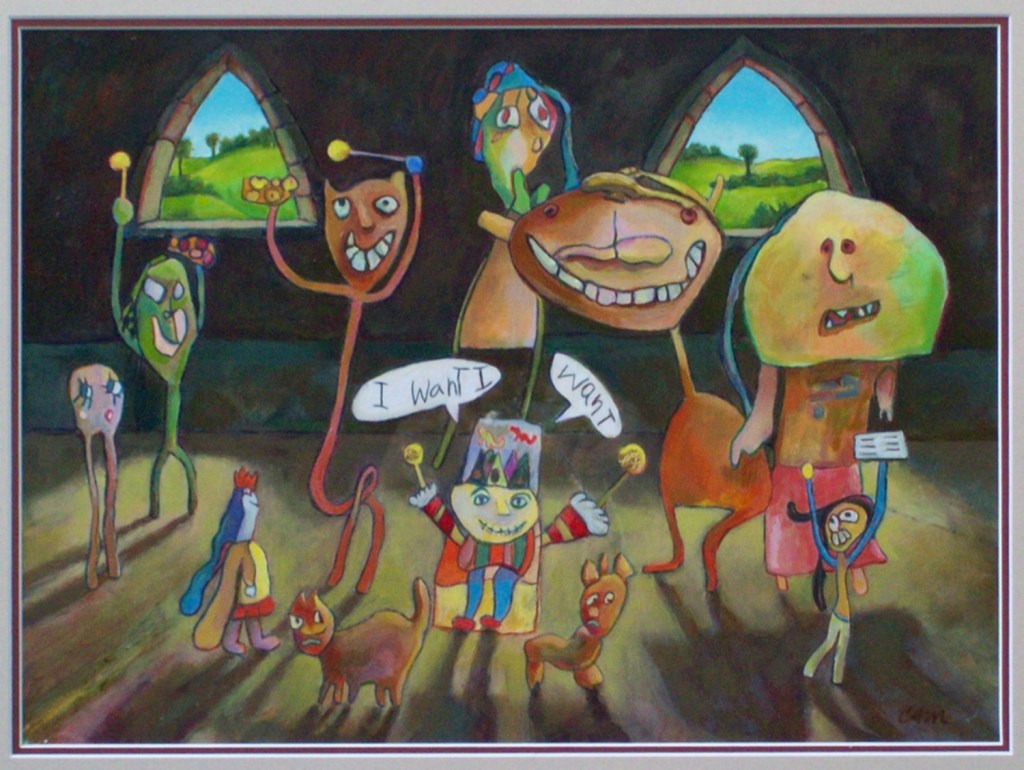

Particularly enjoyable is the “Court of the Covetous King,” in which a joyous little king, surrounded by his gang of monsters (think Maurice Sendak’s Max and his posse of Wild Things), dances around with an impish smile, yelling “I wanT I WanT”! Before the smiley little king are his kitties and behind him is a pair of gothic castle windows that cast a Renaissance light.

What Meader handles surprisingly well, however, are the painterly details. You wouldn’t expect such a court to throw realistic shadows, so it’s fun when they do. And that opens the door to noticing how perfect the light is for the incredible colors. And this is the crux: Any rules are imperfect, incomplete, fleeting and playfully opportunistic.

A girl yells “HelP!” and flees from a sweetly smiling purple blob of a ghost among his similarly joyous friends on a sunshiny day version of Halloween, where scary still means fun. That’s Meader: All the mysteries are fun.

Harold Beskind’s role is to be the complementary straight man to Meader’s warmth and whimsy. Beskind is also past retirement age but new to painting. A psychiatrist and children’s doctor, Beskind is also past pretending he gets what children don’t. And he too is genuinely inspired by the creative imaginations of children. But Beskind looks to children’s transformations of the real world: Sawed-off branches become a flock of assorted birds, a tree becomes an elephant and “Fishing for Fantasies” makes no bones about turning its wet watercolor method into a Rorschach – which helps us all play the same projection game.

Beskind’s bold colors and crudeness of line are no less the source of his charm than his wide-eyed naivete.

While I came to thoroughly enjoy the dialogue between his work and Meader’s, it took a while for me to warm up to Beskind’s brand. But in the context of this show, Beskind is critical component of the conversation. And it’s a conversation well worth having.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.