AUGUSTA — In 2012, after his daughter had been missing for 26 years, Richard Moreau decided to dedicate a gravestone to her next to those of her mother and grandparents.

“Even though her physical remains aren’t there, she’s there in spirit,” said Moreau, 73, of Jay. His daughter, Kimberly Moreau, disappeared on May 9, 1986, when she was just 17 years old. In about a week, it will have been 29 years since he last saw her. “All we know is she came home from school and told her sister that she would be back within an hour,” Moreau said. “She never returned.”

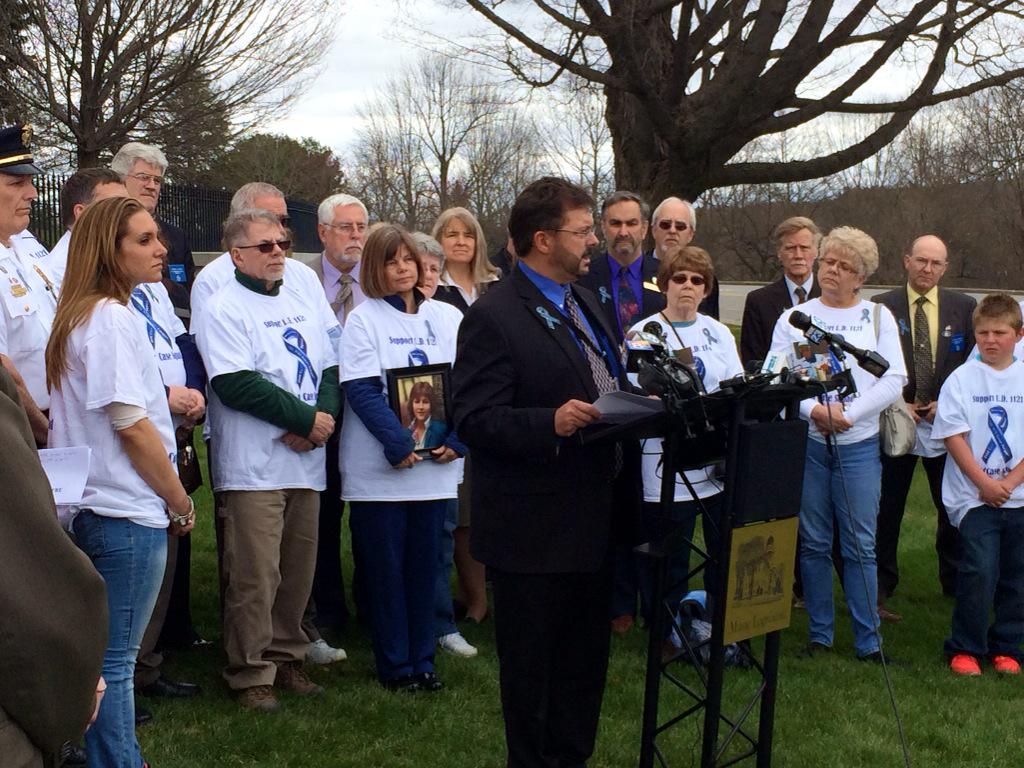

On Wednesday, Moreau was one of several family members of missing people and victims of unsolved homicides who testified at the State House in support of a bill that would provide funding for a Maine State Police cold case squad. The bill, L.D. 1121, is sponsored by Sen. Linda Valentino, D-Saco, and proposes to spend $500,000 in the 2016-17 fiscal year to fund the cold case squad, which was created by state law but has never been funded. The Judiciary Committee voted unanimously to back the bill, and it will now head to the Senate for a vote.

“We owe it to the victims, the families and the public to spend the money so we can take a fresh look at these cases and use modern technology to solve these crimes,” Valentino said during the hearing. There are currently more than 120 unsolved murders in Maine, she said, and the establishment of a permanent cold case squad would ensure that those cases can continue to be reviewed and hopefully solved.

“This bill was about as bipartisan as it can get,” said Rep. Karl Ward, R-Dedham, a co-sponsor of the measure. “It affects everyone. There’s not a single county or a single district that doesn’t have one of these cases.”

The squad was established by a state law enacted in 2002 but was to be funded initially with federal grant money that the state applied for but did not receive, Valentino said.

Before the hearing, dozens of family members of homicide victims and missing persons gathered on the lawn outside the State House, many of them wearing white T-shirts that read “Fund L.D. 1121 Cold Case Squad” and carrying pictures of their loved ones. Among those who spoke was Trista Reynolds, the mother of missing Waterville toddler Ayla Reynolds, who attended the news conference with her two young sons, Raymond and Anthony.

“On December 17, 2011, my world changed,” Reynolds said, recalling the day her daughter disappeared. “I was informed that my little girl was no longer here, and for the last three years I’ve been fighting to get my answers. I’ve had state police tell me they’re doing everything they can, and I still have no answers.”

On the anniversary of Ayla’s disappearance in December, state police said they were continuing to receive and investigate new tips on a weekly basis. Reynolds said Wednesday that since new information continues to be received by police, the case may not be designated a cold case, but she said she still wanted to support other families who don’t know where their loved ones are. The squad would focus on revisiting the 120 unsolved homicides in the state that have had no recent activity, Valentino said, and would include two detectives, a prosecutor and a forensic laboratory technician.

“I don’t want to be one of those moms 30 years from now not knowing what happened,” Reynolds said. “With all the help of every parent that has a missing child, we should try and get it funded so we can bring our children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews home. I have friends that have been murdered and to this day there’s still no one (charged). If we have this funded and we have different eyes looking at the cases, then maybe at the end of the day we’ll all have our answers.”

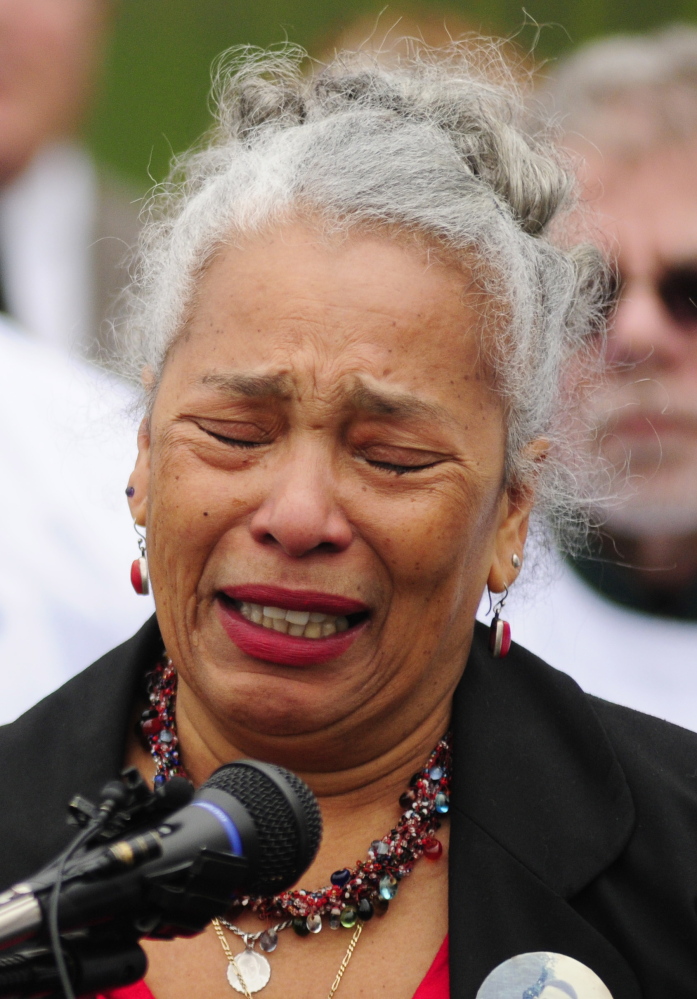

Ramona Torres, of Denmark, also spoke outside the State House, describing the pain she has experienced since the disappearance of her son, Angel Torres, in 1999. Police believe Torres, who was 21 at the time of his disappearance, might have been the victim of a drug-related crime. His body hasn’t been found. “It has been difficult the past week just trying to think of what I want to say,” Torres said, as she wiped away tears. “I think the thing that would come to my mind first is the nightmare we have lived almost the last 16 years. As much as we’ve tried to go on, it is so painful. We are hardworking people. We hold two jobs, and we are asking the community to please pass L.D. 1121. We have too many murders working now, and we don’t have any justice.”

Others who testified at Wednesday’s hearing included law enforcement officials and an assistant attorney general, all of whom spoke in favor of the bill. Charles West, a retired state police lieutenant in New Hampshire who now is assigned to that state’s cold case unit, said that since the unit was formed in 2009, it has led to solving cold case homicides either through arrest and conviction or the identification of a murderer who has since died.

Lisa Marchese, an assistant attorney general in Maine, also testified, saying that while the Office of the Attorney General has a position dedicated to the review of unsolved cases, the state police do not have the funding to do similar work. “They need the funding contemplated by L.D. 1121,” she said. “We can’t guarantee an outcome in an unsolved homicide, but we can increase the chances that they are solved and that we can bring justice to the families.”

Knowing that someone is continuing to work on a case can be a great comfort to the family of a missing person, Moreau said. There have been times when he has not heard anything about his daughter’s case for three or four years. “Every family that I’ve ever talked to has ended up with the same hopeless feeling at the end,” he said. “They don’t know how this works. Just knowing someone is still working on the case is a big plus.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.