TRUMBULL, Conn. — When a basketball-sized swarm of bees decided to camp out at the peak of a decorative arborvitae tree near the Cheesecake Factory in Trumbull last week, the mall maintenance department called an exterminator.

When that exterminator saw honeybees, he called Mike Rice of Roxbury.

“Most responsible exterminators will call us once they see it’s honeybees, because they are endangered,” said beekeeper Rice, of Mike’s Beehives. He’s also Roxbury’s only local police officer.

He’s on the front line of an effort to save the embattled honeybee.

A recent national survey showed an annual loss of 42.1 percent of the nation’s beehives. In Connecticut, the loss was more than 50 percent. In 2006, keepers began noticing increasing numbers of their hives failing, a phenomenon known as “colony collapse disorder.”

POLLINATORS MEET TERMINATORS

It’s alarming news because, according to Kimberly Stoner, a state entomologist, bees are responsible for pollinating about 80 percent of plant species and roughly a third of our food supply. The Obama administration has recognized the urgency of the problem, releasing a pollinator rescue strategy in May that, among other strategies, calls for preserving 7 million acres of habitat.

Rice does his part by rescuing unwanted bees, which he brings to his backyard colonies. He offers free lectures in schools and elsewhere. He builds hives in his basement workshop for himself and growing ranks of enthusiasts. The boxes cost $275. He’s sold about 120 in the past year in Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York.

On Wednesday, just after 6 p.m., a mall maintenance worker lifted Rice on a cherry picker to a massed ball of tens of thousands of bees partially hidden by branches. The bees stick together until scouts find a good location for a new nest, Rice explained.

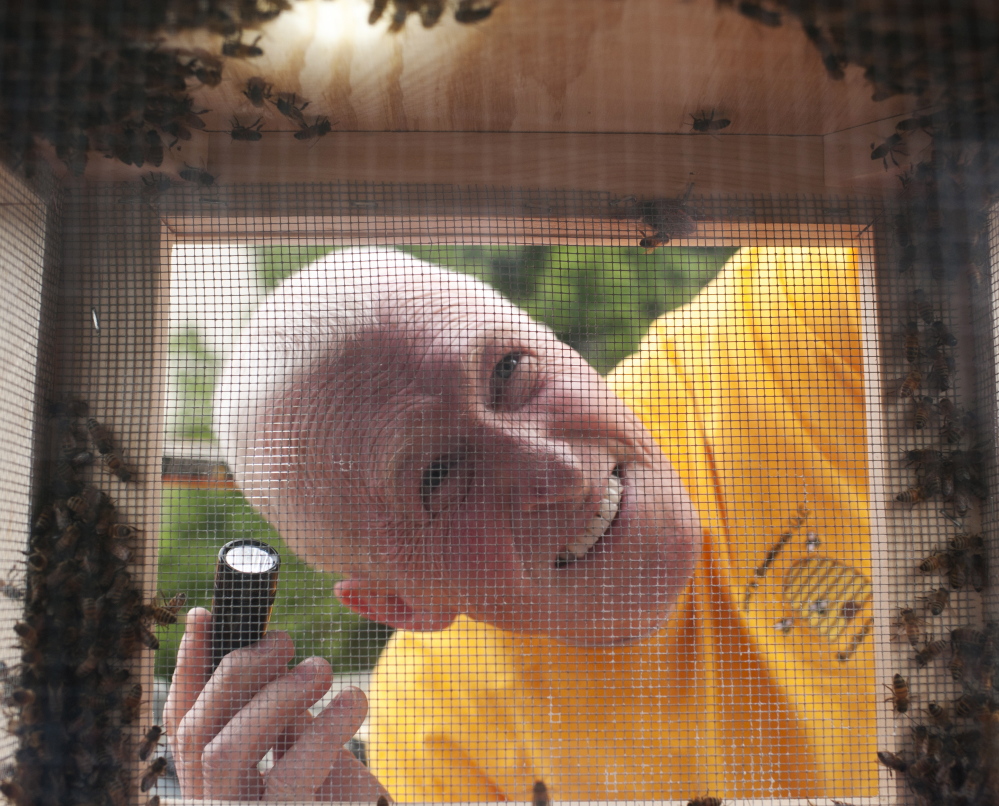

He was armed with a hedge lopper and a box made of wire mesh and wood. He wore no protective gear, just jeans and a yellow long-sleeve shirt. He pruned limbs away from the edge of the swarm. He put the box underneath.

Then he shook the branch vigorously.

Most of the bees, queen included, plopped into the box. Rice gently put on the lid. Hundreds clung to the outside, trying to stay with the queen. Dozens flew around. Some landed on his face and back.

Coming down in the lift, Rice said he was stung only once, on the hand. He’d wait a few minutes for the bees to settle before heading back up to sweep more into the box.

That second time he was stung several times, convincing him to retrieve a protective outfit from his truck. The swarm was so large that a security guard fetched Rice a cardboard box to finish his collection.

UNBEARABLE hazards

In Roxbury, Rice’s 43 hives sit behind an electrified fence, right behind a large garden. Bears have destroyed 10 in the past two years. Colony collapse disorder has claimed another 28.

“It’s like coming down in the morning and finding your dog’s gone,” Rice said. “You just don’t know what to think. I will have hives with 70,000 to 80,000 bees in the middle of summer. I go to close them up for the winter and there’s nothing there. You will have a handful of bees, literally.

“I just don’t know what happened.”

Bees are responsible for pollinating $15 billion worth of crops nationally, said Mark Creighton, the state’s apiary inspector. He’s responsible for inspecting the state’s 7,000 registered honeybee hives, maintained by 850 beekeepers.

Colony collapse disorder is not perfectly understood. Creighton said it’s thought to be caused by a mix of factors: pesticides, disease, bacteria and parasites. Synthetic nicotine pesticides are thought to be a big part of the problem. Today’s commercial seeds are coated in pesticides. Crops grow with pesticides inside the plant, he said.

“They think collectively all of that is the perfect storm creating a lot of stress our bees are under today,” he said.

BAD CHEMISTRY

Creighton said the state itself could do a better job protecting bees. He’s distressed when he sees highway department trucks spraying herbicides along road edges and medians. One fungicide has been found to be lethal when combined in hives with chemicals meant to protect bees from parasites, he said.

“Do we need all this fungicide in our environment? We certainly haven’t done our due diligence on the interaction of all these new chemicals,” Creighton said.

Because Connecticut lost more than half of its bee colonies during the past year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has provided a $12,000 grant for collecting bee specimens, he said. These will be examined at the USDA lab in Maryland and at the University of Maryland to provide a map of parasites and other ailments affecting bees.

Rice picked up beekeeping six years ago. He just suddenly decided it’s something he wanted to do. He gets shipments of bees – 230,000 on a day in May – through the U.S. Postal Service. He uses these and up to 35 rescued colonies per year to replenish his stocks and help new beekeepers start their own hives.

Rice sells honey. He even brews the honey-based alcoholic beverage mead. He makes money selling hives, but loses money keeping bees.

“To help out the bees I suck up that loss,” he said. “They are a huge part of our existence. People don’t realize that.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.