Seventh in an occasional series

First it was medical issues that left Carolyn Balsamo unable to work.

Then her husband had an unexpected stretch of unemployment. With four children to raise, mortgage payments were put off and they pulled their sons out of Boy Scout Webelos to save money. When Antonio Balsamo found work, he had to commute to Boston for the temporary contract position.

Saving for college wasn’t even on the radar.

“We never really had enough to save,” said Carolyn Balsamo.

In all the talk about the nation’s staggering $1 trillion in total student loan debt – higher than the total amount of U.S. credit card debt – one factor is often overlooked: the impact on parents’ finances.

Two-thirds of parents help pay for college, according to Sallie Mae, the nation’s largest private education lender. But the average amount saved in advance by parents is only $10,400, which barely puts a dent in what families are spending on colleges today.

Four years of tuition, fees, room and board at public four-year colleges costs about $75,000 today. At private nonprofit colleges, those costs are almost $165,000.

That means parents find other ways to pay, by dipping into income and savings or borrowing the money. An online poll in March by investment planning company T. Rowe Price found that half of parents said they would be willing to delay retirement, work more or take on a second job to pay for their children’s college education.

College adviser Bill Smith said parents don’t save enough because of the “ostrich effect.”

“I think for a lot of people, college is one of these big expenses, and everyone knows it’s a big expense, and it’s hard to wrap their heads around it,” said Smith, who runs ScholarFits, a Portland-based company advising students and parents on college financial aid.

“People don’t think about it as early and as systematically as I think is helpful for them,” Smith said.

The recession amplified the problem for both parents and children.

“We’re seeing a serious shrinkage in what parents are contributing,” said Marie O’Malley, senior director of consumer research at Sallie Mae. The company annually surveys 800 undergraduates and 800 parents of undergraduates on how they paid for college during the previous academic year.

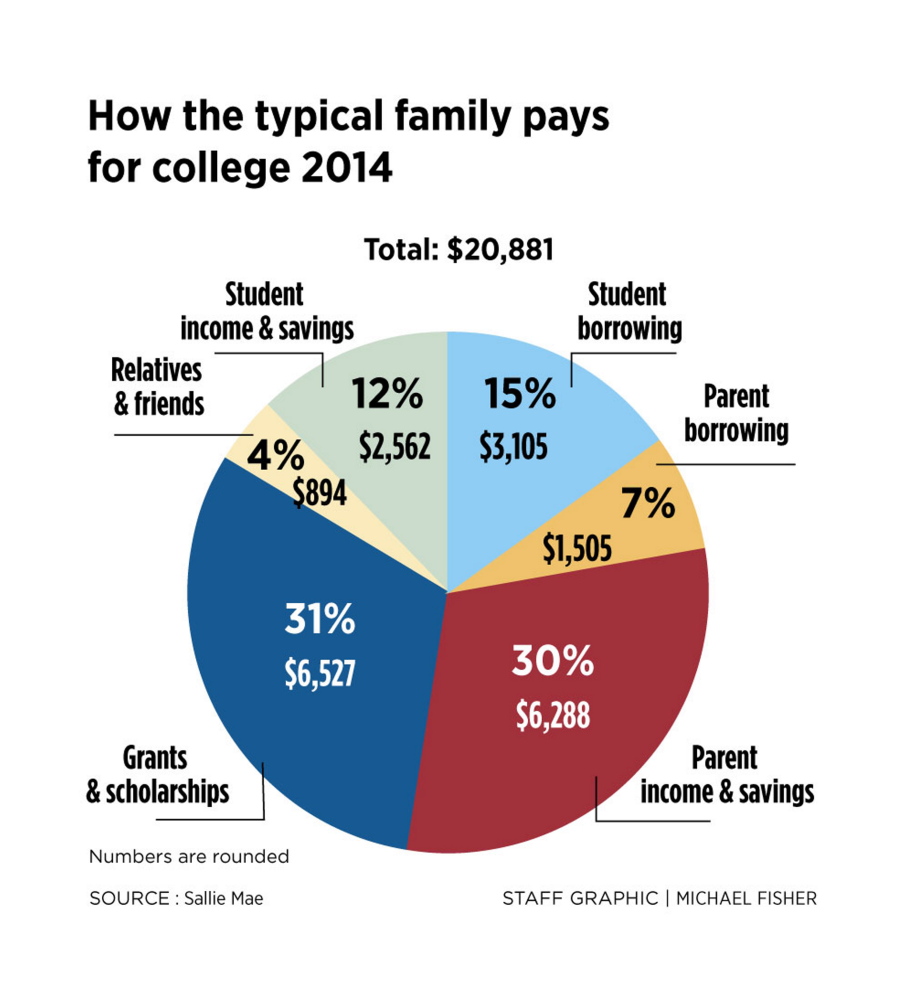

In recent years, the polls found that families have spent about $21,000 a year for college, down from a peak of $24,097 in 2009-10, just as the recession struck.

Families told Sallie Mae they spend less on college, despite rising tuition, because they are cutting costs by having students live at home, start college at a cheaper community college or attend an in-state school, she said.

O’Malley said the belt-tightening is directly tied to the recession.

“Whatever they had planned to use from their savings or investments just wasn’t there, or they lost money or lost income from job losses and had to dip into those college savings,” she said.

PARENTS FORCED TO BORROW

Even parents who save for college can find themselves short when the tuition bill arrives.

While most parents use income and savings to pay for college costs, about 10 percent have to borrow money, according to the Sallie Mae study.

They borrow the money from a range of sources, from federal parent-only loans known as Parent PLUS loans, to credit cards and retirement accounts. That can add up to more debt than the students themselves take on. Maine college graduates carry an average of almost $30,000 in debt, the seventh-highest amount in the nation.

“The student loan debt crisis people talk about may be real, but for many people it’s a parent or family situation,” Smith said.

And that can be stressful because parents are trying to balance the desire to provide their child with the best possible education with the pressure of taking on a realistic amount of debt.

Tom Robustelli, a certified public accountant based in Lewiston, recommends that parents and students start the college search by figuring out what they can afford, then select colleges within that range. If parents let their children just pick out a dream college, the parents and students could get squeezed financially.

“The dynamic is that most parents want the absolutely best for their kids and they want them to reach for their dreams,” said Robustelli. “The reality is you start shopping around for schools and the sticker shock sets in.”

It happened to him when his daughter was accepted at George Washington University, where tuition was $58,000 a year.

“It was the toughest thing I ever did. I had to look her in the eye and say we can’t afford that,” said Robustelli. She immediately suggested taking out student loans to pay for it, an idea he rejected.

“Now that she’s out of school, I think she’s very grateful that she didn’t end up $200,000 in debt,” he said.

LESS TIME TO PAY BACK LOANS

The Balsamos wound up taking out a home equity line of credit on their Saco home to help pay for their daughter’s tuition at a private Pennsylvania college, leaving the family about $35,000 in debt.

Victoria Balsamo graduated this May with a psychology degree and lives at home while looking for work as a counselor.

But the college debt, some of it in student loans, makes it hard for her to move forward, her mother said.

The Balsamos – Carolyn and Tony of Saco – chuckle after getting a high five from the University of Southern Maine’s mascot, Champ the Husky, during their son Robert’s orientation process recently. The Balsamos have struggled to save for school for their four children.

“She wants to find work as a caseworker, but she needs a car to do that. But she doesn’t have one and she can only get one if she borrows the money from us,” Balsamo said. “But it’s a Catch-22 because she says she doesn’t want to owe any more money.”

The Balsamos would like to help her, but with four children between 13 and 22, that means they are looking at 12 straight years of college-age children. They’re paying the interest on the home equity line, but may need to tap into that to help some of their other children with college costs.

To save money, their 18-year-old son, Robert, plans to live at home next year while studying music at the University of Southern Maine. He got some scholarship and grant money, but he’s already taken out student loans. Their 17-year-old hopes to join the military and their 13-year-old dreams of opening up an auto body shop someday, she said.

Parents taking on loans and borrowing against assets need to be cautious since they have less time and opportunity than students to pay back debt, financial experts say.

“You can’t get a loan for retirement,” said Robustelli, who also warns clients not to tap into a poorly funded 401(k) retirement account.

“I think the first thing parents should be concerned about is their own retirement. If they’re not doing that, they have no business raiding those funds,” Robustelli said. “Maybe you could strike a balance, like reducing contributions to a 401(k). That’s reasonable.”

According to Sallie Mae, 7 percent of families said they withdrew an average of $8,870 from their retirement accounts, while 1 percent reported taking out loans against them, for an average amount of $5,062.

FINDING WAYS TO CUT EXPENSES

For Nicole Marsten, changing financial circumstances caught her up short now that it’s time to consider college costs for her 16-year-old son, Noah, who will be a senior next fall at Deering High School in Portland. As a single mother, she couldn’t save anything for his college.

Today, she’s married and works as a senior compliance officer at insurance company Unum, and the family makes too much money to qualify for any financial aid.

“It’s crazy. The system seems to penalize you for making choices when you can’t save,” Marsten said, adding that she’s opened a college savings account for her 9-year-old son. “Now I make a good living, and we’re looking at having to dish out a lot of money.”

Some colleges Noah was considering would have cost more than $40,000 a year.

“Where in the hell does someone think I’m going to pull that off? That is not something I have,” Marsten said.

But she also doesn’t want him taking on a large amount of student debt.

That means a reality check. At the moment, the plan is for the family to cut college costs by having Noah attend USM and live at home.

Just as the recession turned out-of-state vacations into local stay-cations, the education equivalent is deciding to live at home, go to school locally or go to a community college first.

Gianna Marr, director of the financial aid office at the University of Maine in Orono, said her office is flooded with calls in March, April and May, as parents seek help calculating costs and explore borrowing options.

A common thread is parents who haven’t saved enough money.

Sallie Mae found that among the roughly 50 percent of parents who haven’t saved anything for college, 61 percent said it was because they didn’t have enough money to do it. Even for families earning more than $100,000 a year, 45 percent said they didn’t have enough money to save for college.

“We’re not being a good nation of savers, whether it’s for retirement or our children’s college education,” Marr said. “That really puts pressure on students to pay their own way through college.”

Despite tax advantages for some college savings plans, about half the families saving for college just tuck the money into a general savings account, and 23 percent use a checking account, according to a Sallie Mae survey.

Only 27 percent used 529 college savings accounts, which many financial planners recommend because of the tax advantages. Parents control how money in a 529 plan is invested, and the fund grows tax-free until money is withdrawn tax-free for educational purposes. If the intended recipient doesn’t use the money, the fund can be transfered to another qualifying family member or a 10 percent tax penalty can be paid on withdrawal.

Since they were created in 1997, 529s have become increasingly popular. There were 12.1 million 529 savings accounts in the United States at the end of 2014, up 4.1 percent from the year before, according to the College Savings Plan Network. The plans held a record level of $247.9 billion in assets, almost double the $133.4 billion in 2009.

But the group’s year-end report noted that the average balance was $20,474 – about the cost of a single year at a public four-year university.

POSITIVE INFLUENCES ON SAVING

In Maine, the Harold Alfond Foundation automatically awards $500 grants to all babies born as Maine residents for the child’s NextGen 529 college savings account.

Once an account is established, parents can get annual tax deductions for the first $250 contributed each year, and the Finance Authority of Maine gives parents a 50 percent matching grant on the first $200 each year.

And the way parents save can influence how much they save, the Sallie Mae survey found. The average total savings for families using 529 plans was $11,590, compared to $3,419 saved in savings accounts.

Even with savings, many families find they need to pull money from many sources.

Susan Folsom said she’s a saver and a planner, and she’s passing that on to her two sons, 12-year-old T.J. and 9-year-old Wyatt. They both know they’re going to college and regularly put aside money from odd jobs for their own college funds while their parents put money into separate college funds.

“We started saving when they were born,” said Folsom, a counselor at Gardiner Area High School. It’s not the same as when she went to college and her parents just “wrote the checks.”

“I was very fortunate, and I was not able to put away enough for today’s college. They will need aid,” she said, as the trio walked through a college fair hosted by the Portland Sea Dogs.

Folsom said she didn’t mind her sons having to take out some student loans.

“They will take their education very seriously because they will have had a hand in it,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.