“The Paintings of John Calvin Stevens” at the Art Gallery of the University of New England is a major exhibition of scores of paintings and drawings by arguably the most important individual in the development of Maine art.

The personal legacy of John Calvin Stevens (1855-1940) includes the Portland Museum of Art. He designed the museum’s L.D.M. Sweat Memorial Galleries. More importantly, he was a leader and president of the group that founded the museum. And it was he who secured the patronage that made the institution a reality and gave it staying power. But the Portland Society of Art not only founded the PMA, it created what is now the robust and thriving Maine College of Art, which many consider to be the most highly energized art institution in the art-oriented state of Maine.

Stevens designed more than 350 buildings on the Portland peninsula and more than 1,000 in Maine. (It’s not by chance that the University of New England is on Stevens Avenue.) Stevens’ influence, however, went far beyond the buildings he designed in the Northeast. Featuring Stevens’ sketches of his own designs, the 1889 book “Examples of American Domestic Architecture” was the seminal statement of the distinctly American Shingle Style and the Colonial Revival. It made Stevens one of the most influential architects in America. It was his vision that came to embody the standard image of the American house built before 1950.

In short, Stevens was one of the most influential individuals in the history of the American aesthetic.

Behind Stevens’ persuasiveness was his artistic ability. His images were widely published in the most influential architectural publications at a time when architects relied on their ability to draw. Leading architects such as Stanford White, H. Van Buren Magonigle and many of their peers must be considered among the most accomplished American visual artists. (Frank Lloyd Wright’s story of success is similar: The narrative of his worldwide influence begins with the 1910 publication in Germany of his Wasmuth Portfolio, which came to be seen as a defining statement of the International Style.)

In other words, we aren’t looking at Stevens’ paintings because he was an influential architect. Rather, he became an influential architect because he was a great artist.

Stevens was a peer of Winslow Homer, not only because he designed Homer’s house and studio, but as a fellow painter. They were friends and Stevens was delighted to find that America’s greatest painter was “pleased to give advice freely.” Homer even gave one of his masterpieces to Stevens: the 1894 “The Artist’s Studio in an Afternoon Fog” now owned by the University of Rochester but exhibited recently at the Portland Museum of Art.

Stevens’ American Impressionist-style paintings are accomplished and structurally complex for works largely produced with the Sunday painters’ group, the Brush’uns, with whom he painted religiously for decades.

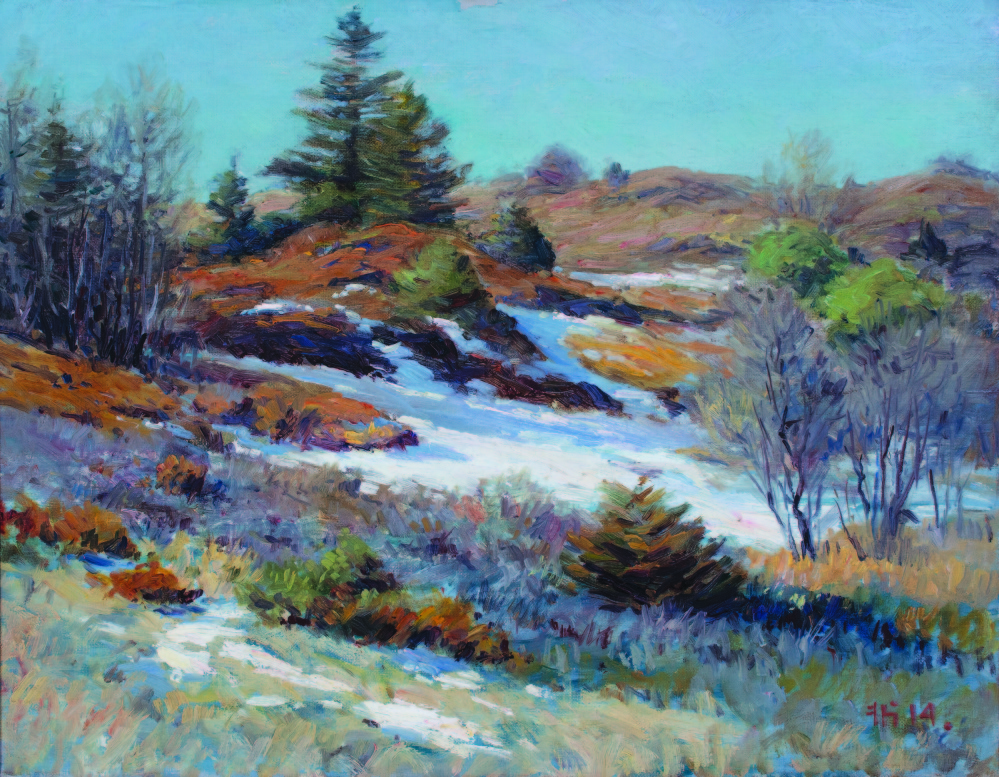

“November Snow” (1914), for example, features a spare but craggy and autumnal hillside. It is beautifully painted with a quick and flickering brush. Our eyes circle in from the sentry pine at the top left and swoop down on descending diagonals from the upper left to the lower right, where our gaze is lifted back up through now-grayed trees to the upper horizon line on the crest of the hill to start the circuit again.

While this dynamic visual structure is a common approach, Stevens’ vision as an architect is more often his guide. What architects create, after all, is less about things than spaces for people. What tends to matter most for architecture is egress, the path out of a place. Besides the impressive brushwork, color, light and formal composition, the most rigorous guide of Stevens’ paintings is his sense of path.

“Path Through Delano Woods” (1913) is an excellent example of Stevens’ work. It depicts a two-track road through a woody landscape. The light pops the deciduous growth in the foreground, warmly yellow chartreuse with its early season leaves. The path curves off to the right before a backdrop of cool spruce green pines. The right track lies at the very center of the image, and it is aligned with our perspective. We are on that path. And because we move on the right side of the road, we have the sense of walking forward.

We see this path logic again and again. It leads not only our eyes into the work, but our bodies as well. It moves us into the scene. In “Winter Landscape” (1911), for example, we follow the tracks of our fellow trekker, his scarf blown straight by the chilly wind, back toward the warmth of the distant house announcing a fire in its hearth by the smoke blowing sideways from its chimney.

The path approach is clear but carries subtle implications; it’s no less structural than a tool for empathy. “The Dividing Line” (1914) brilliantly follows an old stone fence over a seaside berm. The space is easy for us to understand, and the stone fence reveals the labor of its own making.

Above all, the exhibition makes the case that Stevens, who showed his paintings regularly in Maine, New York and Boston, was a significant American Impressionist painter. While the body of work is impressive, the majority of the work is strong enough to stand on its own in any collection of American painting. “Burning Off” (1914) and “Seascape” (n.d.) are excellent marine landscapes that echo Homer but do not bow to him. “Easter Sunday” (1914) and “Beech Tree, Great Diamond Island” (1901) are just two of many crisply painted scenes that can be appreciated for Stevens’ sense of stroke, draftsmanship, light, structure, description and atmosphere.

Of course, at the base of the show are Stevens’ drawings. With dozens on view, it’s easy to see how they were the wellspring of his success. Stevens had been accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology architecture program but could not afford to matriculate. So he learned architecture through the hard work of apprenticeship. Maybe it was this approach that turned him into a lifelong student of drawing.

Whatever the source of his abilities, the fruits of Stevens’ hard work and skill changed the look of Portland, Maine and America.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.