BERWICK — Working swiftly, Beth Wittenberg stenciled a hypodermic needle and the words “Heroin Kills” on a peeling industrial wall across from Berwick Town Hall. Underneath, she provided a helpline phone number.

Within a day, the drawing was painted over.

Earlier in the spring, Wittenberg, 49, hung panels of paintings from her provocative “Beasts, Buildings & Storms” series in a vacant storefront in Rochester, New Hampshire, her hometown. Within a week, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, which arranged the pop-up show, took it down, citing a desire to rotate the work of different artists through the downtown space.

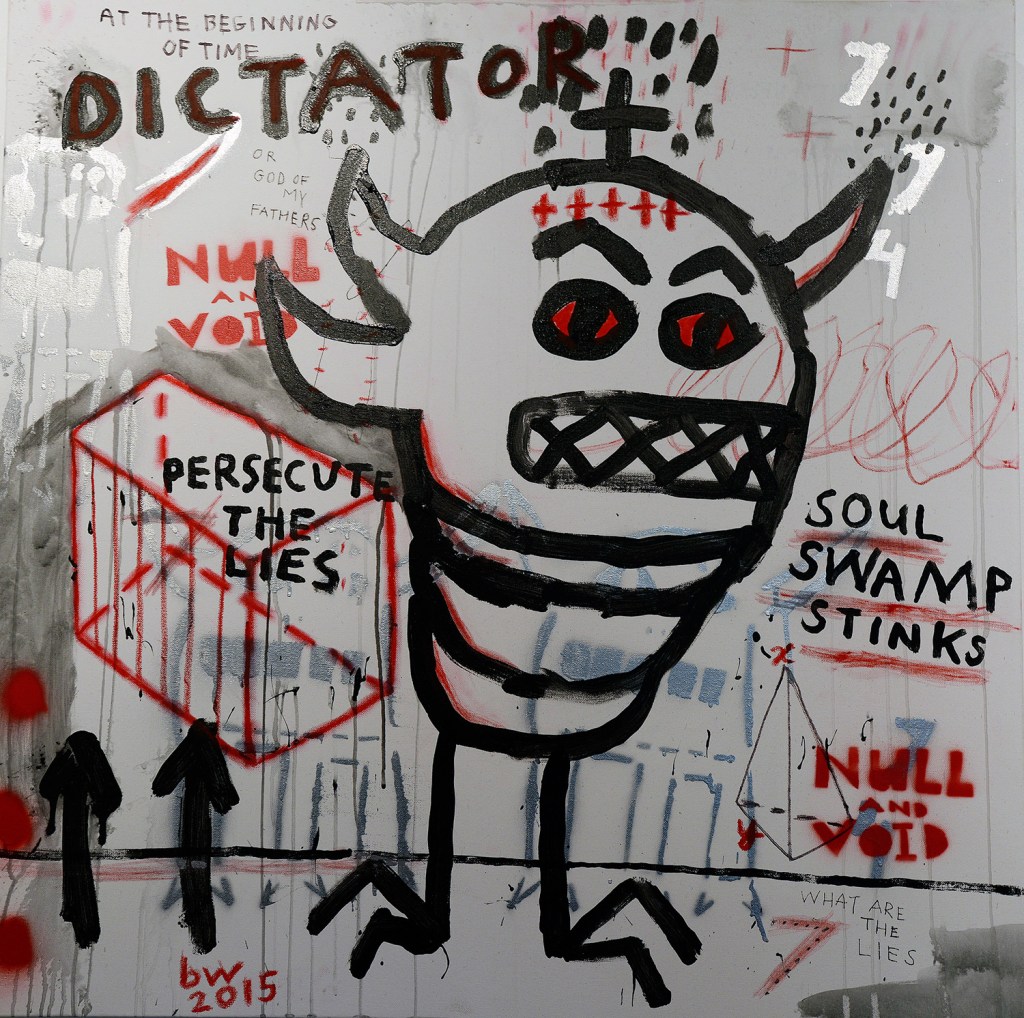

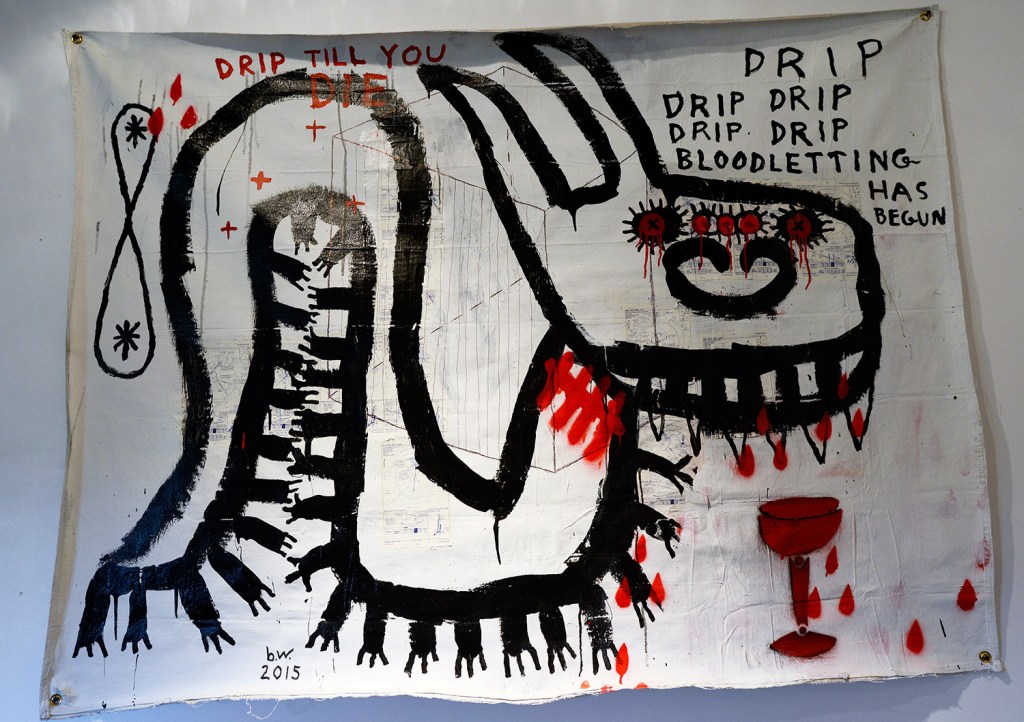

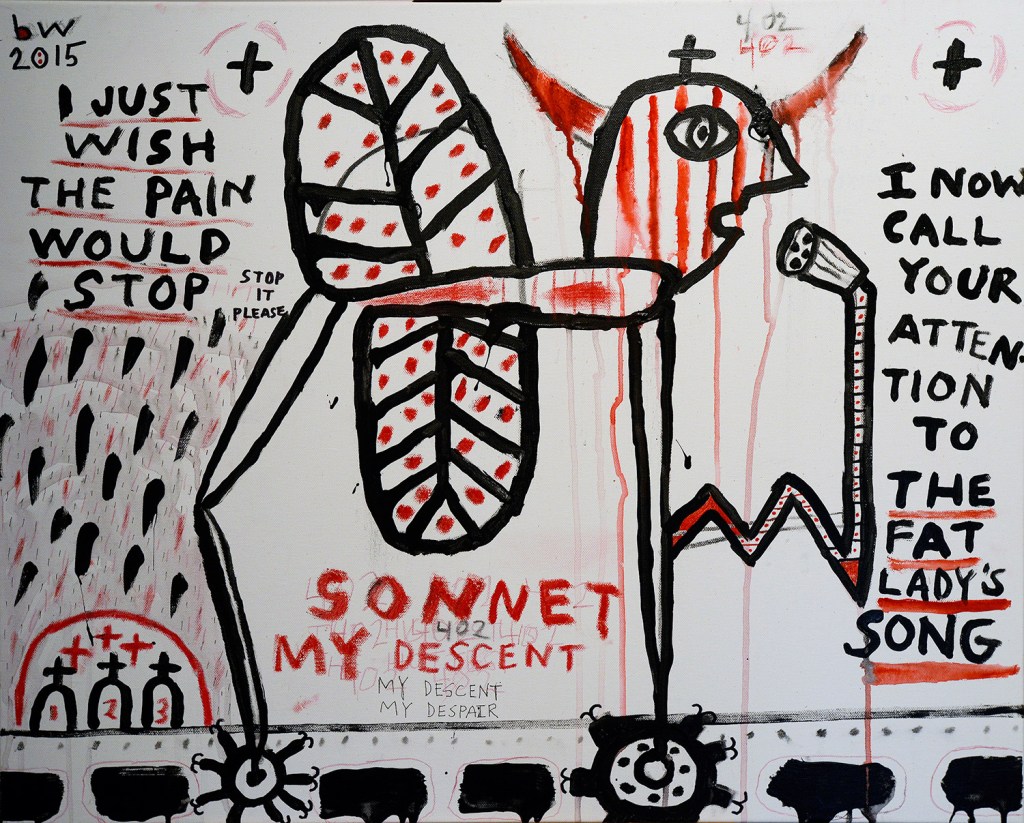

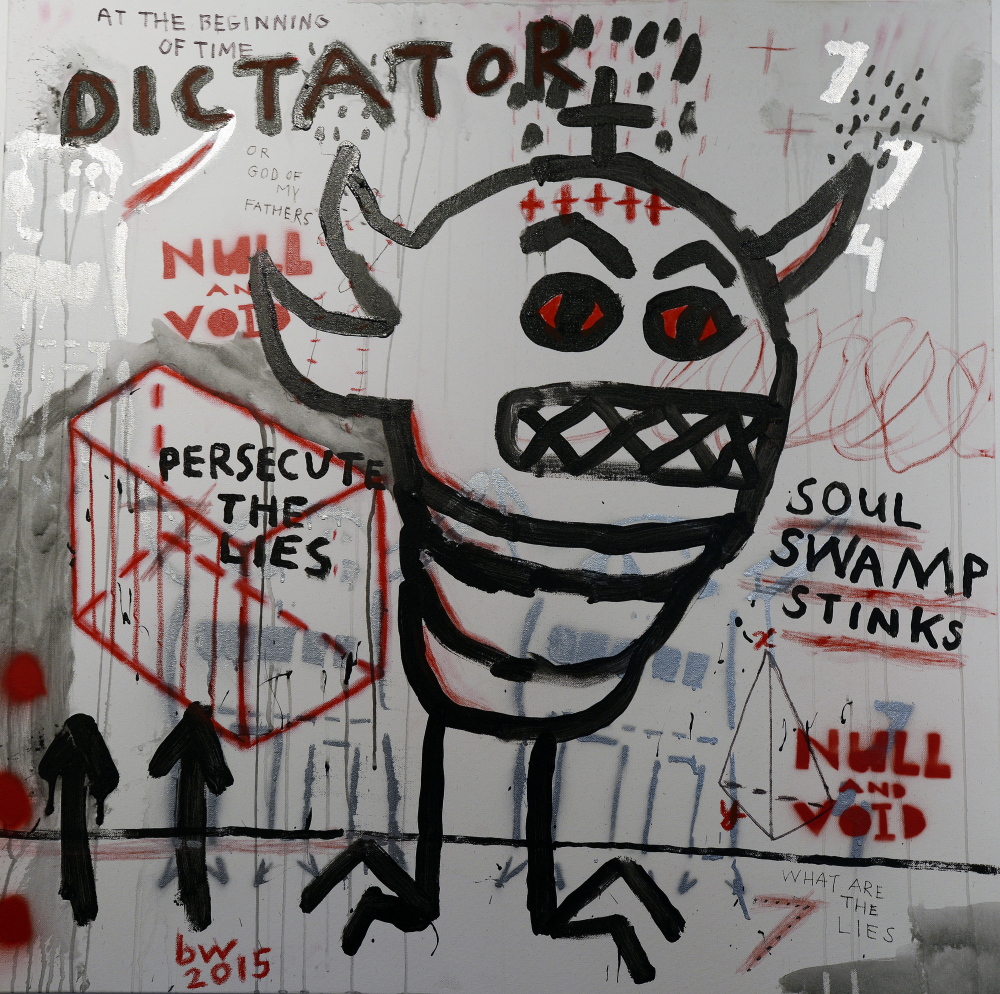

In both instances, Wittenberg felt she had been silenced. People complained that her paintings offended, with their hints of German expressionism, crude language and alien beasts acting out the sins and weaknesses of mankind.

In Berwick, Wittenberg reacted in anger to a friend’s overdose and expressed herself on the largest wall she could find, a flecked, peeling green and white blight of urban decay from a tannery long abandoned.

In Rochester, she hung angry, bleak paintings about violence, degradation and abuse, and lighted them at night so they shone like diamonds. They were difficult to ignore, and Wittenberg understands why people were upset. A downtown storefront in a small New England city wasn’t a wise setting for her activist art, she conceded. “It wasn’t appropriate for the street. If I had children, I wouldn’t want them standing in front of it reading out loud,” she said.

And therein lie the challenges of being a street artist in rural America. Wittenberg has something to say, and nowhere to say it. She needs buildings to tag, windows to paint.

Instead, she’s improvises. She’s taken the guerrilla approach of an urban artist and adapted it to her rural lifestyle.

She makes paintings on cardboard, plants them on the side of the road for motorists to see, then lets them deteriorate in the rain. Instead of tagging buildings illegally, she now reproduces her anti-heroin graffiti as original poster art and distributes posters through community and arts organizations. And rather than risk offending her neighbors by hanging paintings in a downtown storefront, she showed them last month in a North Berwick art gallery, where she could talk seriously about her work with people who cared.

She appreciates living in a rural area “where what’s in front of my eyes is beautiful.”

“Living rurally affords me the opportunity to go inside, to open up my receivers and have a spiritual conversation,” she said.

That conversation often ends in angst. Her “Beasts, Buildings & Storms” series expresses emotional turmoil and distress. Her beasts represent humans at their worst. Buildings are our gathering places, where we live and work. Storms represent emotional clouds.

In her recent past, Wittenberg made small colorful paintings and drawings of monsters who were less edgy, more playful. Her work has become less refined, larger in scale and more simple in color. Right now, she’s using black, white and red.

“It’s the stuff people don’t want to look at,” she said of the content of her paintings. “There are a lot of dark issues here, a lot of pain. It’s dark, because that’s life. It’s the other side of joy.”

Erin Thomas, an artist from Berwick, appreciates Wittenberg’s unfiltered honesty.

“She has a unique ability to tap into her immediate psyche while she’s creating, producing effects that can be both very tragic and beautiful while remaining always communicative of the human condition,” Thomas said. “I see her work as a manifestation of thought, rather than a rendering of a tangible reality.”

The death of a friend to a heroin overdose triggered Wittenberg’s recent outrage. She’s always used art to respond to a moment. Her response in Berwick was spontaneous, and, she hoped, positive.

She enlisted the help of a studio mate, grabbed her paints and headed to the former Prime Tanning building, which the town acquired in November. It’s been vacant a decade. Weeds and small trees grow around the chain link fence. The Berwick Art Association, of which Wittenberg is a member, hosted a painting project to clean up the wall. But free paint only goes so far on a wall as big as a city block.

Wittenberg hit it quickly on a spring morning, making three quick passes with stencils and spray paint.

She’s not surprised it got covered up in a day, and Wittenberg has never been asked to answer for her action – vandalism of public property. But she’s still perplexed. “I think what we were doing was a positive thing,” she said. “Heroin is a huge issue in rural New England. A lot of people are facing addiction. The idea was to put the message at the street level, so perhaps someone walking by was an addict, saw it and decided to make a call.”

Tammy Ackerman, executive director of the Biddeford civic and arts organization Engine, decided to frame the conversation around a socially aware artist trying to make a statement, versus a graffiti artist leaving a mark on a privately owned building. She urged Wittenberg to work within the system and established protocols to get her message to a wider audience.

Wittenberg began making posters, which Ackerman helped distribute. And instead of being angry about feeling silenced, Wittenberg has found a way to put her “heroin kills” message in front of people who might benefit. “It’s still being talked about, which is great,” she said.

She’s also getting recognized. This spring, a local newspaper gave her an award for her work, and Wittenberg continues to find ways to show her art. This summer, she is showing paintings in a body piercing shop in Dover, New Hampshire.

She’d rather show them in a gallery in Portland, Boston or New York. Until then, she keeps painting and hoping people notice.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.